“I promised myself I would be a success in New York.” Following her mentor Georgia O’Keeffe’s advice, in 1958 a young Yayoi Kusama left her rural Japanese hometown behind and moved to New York City. Kusama’s family vehemently disapproved of her passion and finally confronted her with an ultimatum; it was them or painting. Of course, we know how that story went. But in a (white) male-dominated art world, Kusama’s road to said ‘success’ proved to be long and brutal. The hostility she was met with, however, wouldn’t deter her. Kusama did absolutely anything and everything to be noticed.

After a traumatic year of being rejected from every gallery and living in poverty, someone recognised her talent – it was none other than the minimalist American artist, Donald Judd. Abstract expressionism was having its heyday but as soon as Judd saw Kusama’s original “Infinity” paintings, he was hooked. Judd gave Kusama’s first exhibition a rave review, and they would go on to be lifelong friends.

Soon enough, other major modern art world players began to pay attention to. Kusama’s work —slowly—started to receive a small fraction of the attention it deserved. Fellow artists at the time (namely Andy Warhol) took such a liking to Kusama’s work, in fact, they started to copy it and call it their own. Meanwhile, America’s post-WWII animosity towards Asian people (specifically Japanese) cast a dark shadow on the artist’s existence. Kusama’s fierce dedication to her work, though, became a way to process the bombardment of racism and sexism, along with the haunting memories of her childhood in Japan. The artist turned to painting not to escape, but to survive. This symbiotic relationship continues to inform her work even now.

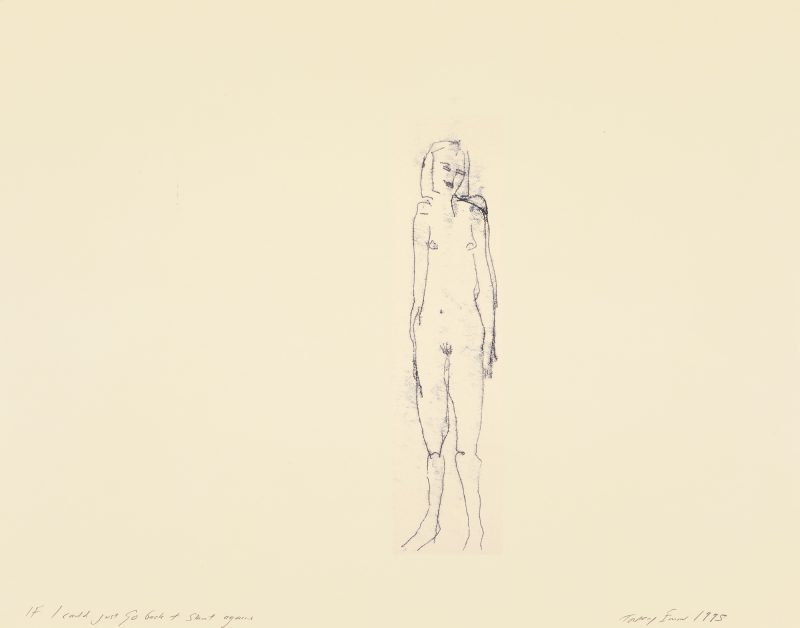

Kusama began making art at age ten and was immediately “moved” by drawing and painting the dots that would become her signature. She worked fast and furiously and the physical and emotional act of making art, much to her family’s dismay, quickly consumed her. Though Kusama’s work is beautiful, (the current exhibition at Tate Modern, Infinity Mirror Rooms, is no exception) it is critical to remember that struggle defines this artist’s story.

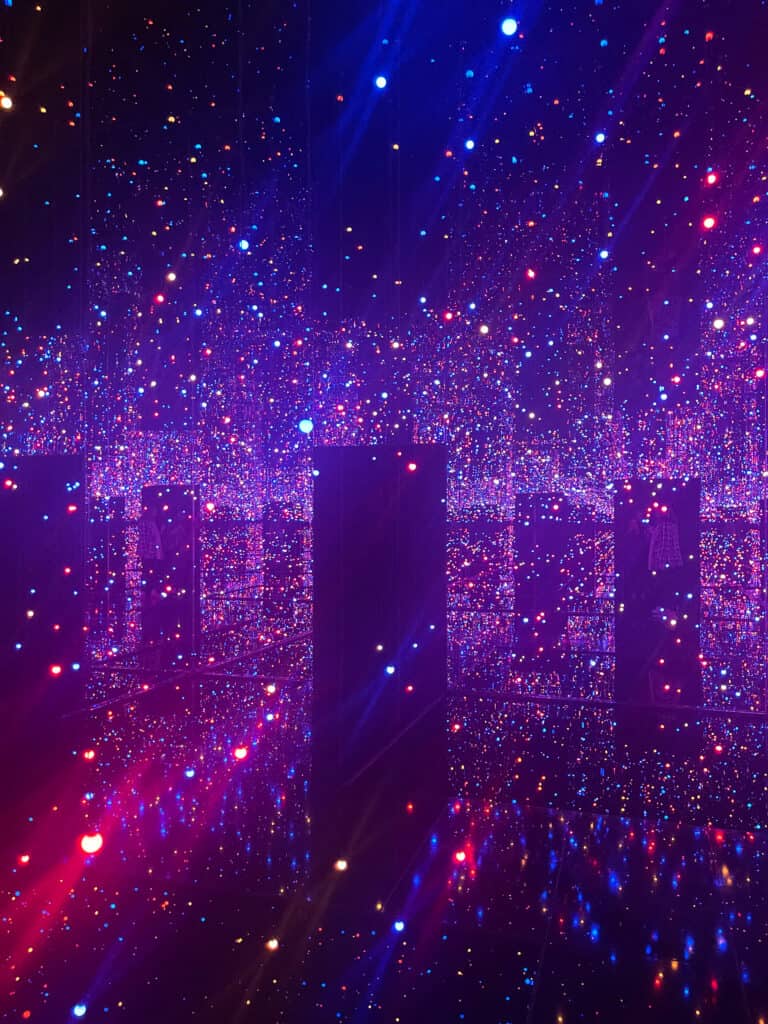

The “Infinity Rooms” have become one of the most publicized pieces in our contemporary art world and for a good reason. The rooms are unapologetically photogenic; their instagrammable qualities are blatant and forthcoming. Viewers only have a couple of minutes in the space (thank you, Covid) and they are forced to choose between fully engaging in the sensory overload that surrounds them or documenting it through videos and photographs of their own. I was one of these viewers, and if I am honest, I struggled with this choice myself.

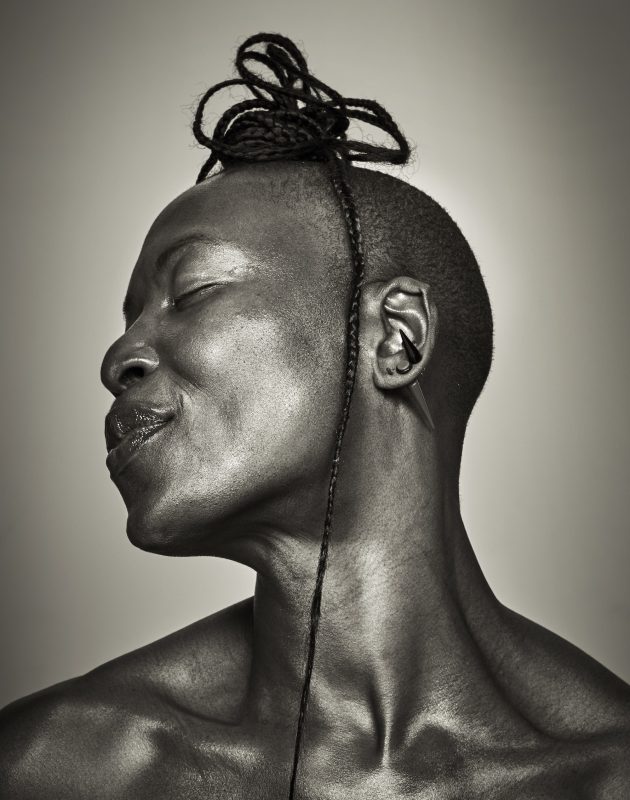

A timeline of sorts lines the walls outside of the rooms, documenting Kusama’s early, middle and latest achievements. It is complete with intimate portraits of the artist (performing, creating etc.) by Japanese photographer Eikoh Hosoe. He captures the dichotomy, juxtaposition, and disparity of the beautiful, silly, yet incredibly serious Kusama brilliantly. The timeline is essential as it places Kusama in various stages of her life and exhibition goers can then emotionally engage with her story whilst physically handling the sensual experience of the iconic infinity rooms.

Ultimately, though, what cannot be captured in videos and photographs (no matter how many one takes,) are the deep-seated complexities of the artist’s mental health. These have not only defined Kusama’s life and work but also inspire a uniquely intense duality of emotion—beauty and tragedy, grief and euphoria. When physically immersed in these swirling, sparkling spaces this all-consuming aura cannot be ignored. Viewers continue to marvel at Kusama’s ability to create awe-inspiring works of art in the face of such suffering. But the irony is the answer lies in the genius of her mind.

Yayoi Kusama Infinity Mirrored Room – 12th June 2022 tate.org.uk