While another Blockbuster Hockney exhibition opens in the main galleries of the Royal Academy of Arts, aptly featuring a vast suite of iPad paintings depicting spring during lockdown in Normandy last year, the real gem of a show can be found upstairs in the Sackler Wing. Filling the walls of the Sackler galleries with a collection of huge, sumptuous paintings featuring a cacophony of colourful animals and characters, is Michael Armitage, a Kenyan-born artist living between Nairobi and London who is reinventing painting for a 21st century audience through the lens of East African history and culture. There is something so visceral about paint on canvas – and about the free, expressive style in which Armitage paints – that seeing this exhibition in real life is a perfect antidote to the many months of seeing images on screens during lockdown. Michael Armitage Paradise Edict is a perfect exhibition with which to reopen after lockdown 3.0, for his canvases stir the senses far more than any images created digitally, proving the transformative effect that art can have and reaffirming the importance of art to our psyche.

Inhabiting a fantastical reality where multiple threads of narrative are weaved together – from the politics of East Africa to religious ideology and mythology – Armitage’s paintings reflect the chaos of modern life through an insightful observation of social dynamics. Although his paintings have hints of revered Western artists such as Gaugin (the Post-impressionist palette and exotic landscapes) and Goya (skilfully drawn expressions of agony, ecstasy, and mischief), his is a completely unique style that subverts cultural cliches and Western stereotypes of the African diaspora and reimagines ancient Greek myths in a 21st Century West African context. Although there are hints of Gaugin in Armitage’s style, he counteracts Gaugin’s cultural appropriation and exoticized Western stereotypes of Tahitian women, by portraying the characters in his own paintings far more authentically and honestly. The vibrant, chaotic, magical realism of Armitage’s canvases depicting East African life and death, humans, and nature, could be described as the painterly version of Gael Garcia Marquez’s Latin American literary masterpieces.

Armitage was born in Kenya in 1984 and his paintings are infused with knowledge of European art history mixed with a love of East African contemporary art. His unique style infuses magical realism with lived experiences of political unrest. As striking as his bold imagery and palette is the material Armitage paints on – a canvas crafted from Lubugo bark cloth, a culturally significant material made from tree bark by the Baganda people in Uganda. I first saw Armitage’s painting Pathos and the twilight of the idle (2019) in the Arsenale Exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 2019, and the painting is on display now in the RA show. Armitage was a post-graduate student at the Royal Academy Schools a decade ago, and this year he revisits his Alma Mater with 15 large-scale paintings completed over the past 6 years on display in the Sackler Wing of the Royal Academy of Arts.

The vivid tableaux exhibited at the Royal Academy include The Fourth Estate (2017), which depicts a group of people at a political rally in Uhuru Park, Nairobi, which Armitage attended during the contested 2017 Kenyan elections. In the painting Armitage references Francisco de Goya’s 19th Century Disparate Ridiculo (Ridiculous Folly) print by including figures perched in a tree. He uses narrative painting to subvert traditional codes of representation, creating a new visual vocabulary with images that recur in his paintings, such as a toad, which symbolises political deceit. His paintings depict political unrest and social inequality, with the vibrant palette masking an underlying current of a more sinister reality.

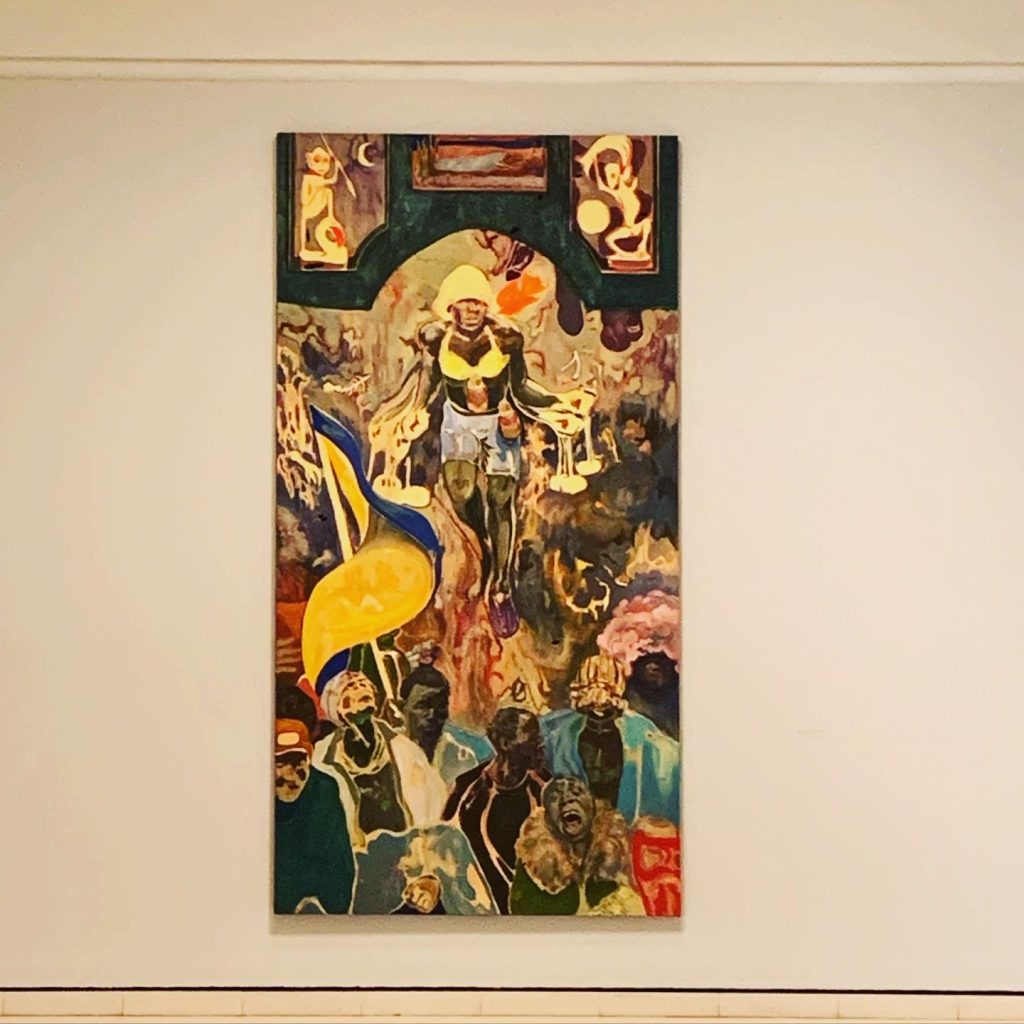

Pathos and the twilight of the idle (2019) is a vast painting with a composition resembling a Renaissance altarpiece, with a figure at its centre seemingly floating in mid-air, arms outstretched and holding some sort of vessels. Armitage has borrowed a pose from Titian’s 16th century altarpiece The Assumption of the Virgin and translated it into a contemporary depiction of a 21st Century political rally in Kenya, with the central character striking a pose of a political martyr.

One of the most striking paintings is Antigone (2018), a powerful nude portrait of an African woman which reimagines a legendary Greek tragedy in contemporary East Africa. By naming her Antigone after the Greek tragedy in which the daughter of Oedipus defied the orders of the King, consequently losing her life, Armitage references the pressure African women are sometimes under to marry to secure social status. Armitage’s Antigone meets the viewer with an unflinching, confident gaze befitting a confident African woman.

The exhibition also features a room dedicated to the work of 6 East African contemporary artists selected by Armitage; Meek Gichugu, Jak Katarikawe, Theresa Musoke, Asaph Ng’ethe Macua, Elimo Njau and Sane Wadu.

In a 2014 article published by the Art Fund, academic Eddie Chambers explored why so many black artists have been neglected in art history, saying: The absence of black artists from major books and catalogues of British art is a somewhat circular occurrence. The view, openly expressed up until the 1980s, was that black artists didn’t really exist. After all, how could they, when there was precious little ‘evidence’ of them in books, galleries, and museums? Thus, black artists have found their absence to be reinforced, time and again, leading to the formidable impression that they did not really exist. The art world would look very different if successive generations of black artists had not been kept out in the cold, for decade after decade. Are things changing for the better? Certainly, the likes of the Tracy Emins, the Damien Hirsts and the Grayson Perrys referred to earlier have been joined, since the mid 1990s, by the likes of Steve McQueen, Chris Ofili and Yinka Shonibare. But only time will tell if progress really has been made.

Thankfully, in recent years progress has been made, and the contemporary art world has finally sat up and taken notice of black artists and given them a long overdue time in the spotlight. With this new solo exhibition and at the young age of 37, Michael Armitage proves himself to be such a vital, energetic force in painting that there is no chance anyone would dare to omit him from art history books of the future, there is more chance that he is rewriting the white-washed history books and redressing the balance for future generations.

Paradise Edict is curated by Anna Schneider (Haus der Kunst) with Dr. Anna Ferrari (Royal Academy of Arts).