Perrotin gallery to present Tehachapi, a solo exhibition by French artist JR. In October 2019, JR received permission to work in a maximum-security prison located in Tehachapi, California. Initially, JR went there to meet twenty-eight prisoners and present an idea for a collaborative, artistic project in the central yard.

At Tehachapi, the majority of the incarcerated population has been imprisoned for nearly a decade, with many sentenced to life with no chance of parole. Due to California’s Three Strikes law.

Today, nearly half of the inmates sentenced under the law are serving for nonviolent crimes.

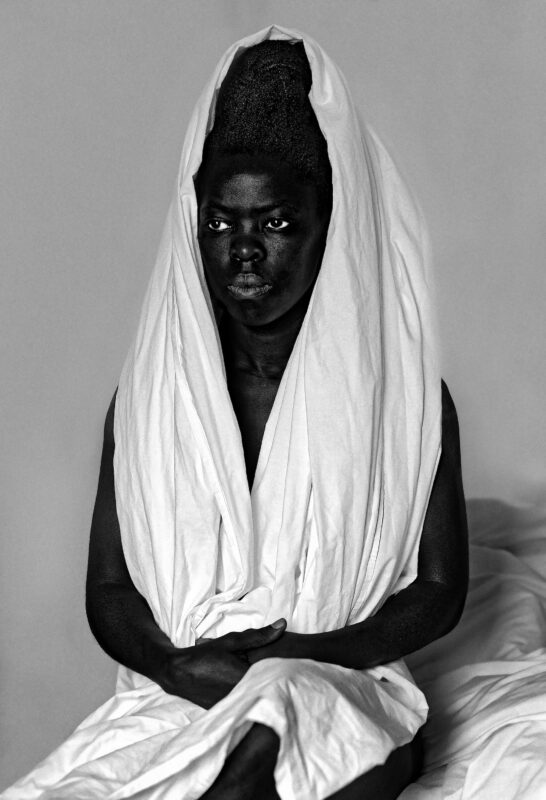

JR photographed the men, one by one, from above, and they told their story in front of a camera. No specific questions were asked; they had the freedom to tell express themselves candidly. JR also photographed former prisoners and prison staff, collecting a total of forty-eight portraits and stories from the prison system. Two weeks later, JR returned with his team to paste 338 strips of paper to the ground. Under an autumn sun, in just a few hours, the prison’s incarcerated populated worked with guards, former inmates, while members of JR’s studio, equipped with push brooms and wallpaper glue, completed the prison yard collage. The strips of paper were numbered so they could be assembled side by side to form a giant puzzle. From the prison yard, the final installation image is indiscernible. Yet, from above, it becomes clear — incarcerated people, former inmates, as well as the prison staff, and victims stand shoulder to shoulder. The installation, naturally ephemeral, disappeared in three days under the footsteps of the prisoners.

In February 2020, JR returned to the California Correctional Institution in Tehachapi to continue doing what he does best — creating powerful, largescale wall pastings that disappear over time. Inspired by the Tehachapi Mountains, which lie just out of view from the central yard of the complex, and working collectively with volunteers composed of the prisoners, JR conjured up a wheat-pasted mountain range across the surface of the courtyard’s inner wall. The installation still remains today.

Anamorphosis

Anamorphosis is a visual technique that utilizes the reversible deformation of an image through an optical system or a mathematical transformation. In the case of Tehachapi, the viewpoint that reveals the image is accessible

only from above – here, using a drone. In the past, JR has frequently employed anamorphosis within his practice:

on a staircase in a favela in Brazil, a row of buildings in Marseille, and more recently, surrounding the Louvre’s Pyramid. For this particular project, which took place in March of 2019, JR ideated a monumental collage across the Cour Napoléon at the Louvre. With the help of hundreds of volunteers, the final installation was composed of 2,000 strips of glued paper.

This monumental, ephemeral, and collaborative work was only visible from one of the Louvre’s archive rooms where a camera was installed to document the evolution of the project.

Bridges

In the same way that the Louvre collage would not have been possible without the participation of the general public, the two Tehachapi collages are collaborative works with the prisoners, former inmates, prison staff, as well as JR’s team. Like the visual itself, the interactions between the various participants are an integral part of the project.

Working towards a common goal that – on the surface – has no useful function, becomes both a bridge and a pretext for a larger conversation. Since the completion of the project, a number of the inmates formed a working

group to begin art classes, and JR continues to stay in touch in order to maintain the long-term goals of the project.

Inside Out

The extraordinary and exceptional nature of this project, for the artist as well as for the participants, interrupts quotidian life. At its core, it is a disruption of a highly regulated system through the introduction of an artistic element

that hinges on collaboration, reflection and solidarity. Why introduce a large-scale art installation into the middle of California’s desert on a concrete and sand yard? The majority of JR’s installations have occupied unexpected spaces: A neighbourhood in Kenya, a container ship, across the US and Mexico border. We use art to ask questions — Can art be a vehicle for social change? Can it shed new light and raise questions about the correctional system in the United States?

To learn more about the project Tehachapi, you can download the free app for iPhone and for Android: explore the image and listen to all the participant’s stories.

JR TEHACHAPI 29th August – 26th September 2020 Paris perrotin.com

“I have been continually interested in the prison system. After all, prisons are made of so many walls, which have formed the foundation of my practice. I did a project a few years ago at Rikers Island, and it was a fascinating experience because time moves slowly in a prison. When those inside are confronted with something new, it quickly becomes important and the community invests so much energy into each project. A friend called me recently to say there was a possibility to access a prison in California. At first, I thought it would be too much paperwork and too many constraints. Fortunately, a former participant from The Chronicles of San Francisco was able to facilitate. So, with Google Earth, I searched through all 35 of California’s state prisons, and I chose Tehachapi without knowing it was a maximum-security prison. Seen from the sky, the concrete prison yard, architecturally, seemed to lend itself to a large-scale community installation.

The idea was to engage with men working through the rehabilitation process, formerly incarcerated men, family members, the prison staff, as well as those who sought reconciliation, including victims and their families. When I got there, I understood that most of these men were incarcerated when they were teenagers, between 13 and 20 years old, many of them for life. I told them about my project and made it clear that I did not need to know what they were accused of unless they wanted to speak of it. They had a trial and they were sentenced. I am not their judge. Nevertheless, a few left the room as they felt that their participation in the project would not be welcomed by their families or for the families of their victims. A number of them were in prison for life because of the three strikes law in California. Some will be freed because the law has changed since they entered prison. During the process, I was allowed to use my phone and I shared stories about the installation on social media. I received reactions from all around the world, from their families, from victims, from critics, as well as those shocked by what they saw, including tattoos of a swastika. I shared these reactions and we spoke about them. The families of the inmates also replied on social media and there was a connection between the inside and the outside for a brief moment. Once the piece was completed, we decided to wait for a couple of weeks so we could put together a platform for everyone to hear the stories. Why? Because we know that it is a sensitive subject and we wanted everyone to be able to listen to stories of hope and redemption, as well as hearing testimonies that are routinely silenced. What happened in that yard — when these men, alongside guards as well as victims, came together collectively for a singular vision — has to be seen. We wanted to share the process and embrace the complexity of human actions and feelings. These men have been judged guilty when they were young; some were forced into gangs and mistakes were made. They have paid the price; some are still paying.

The final image was captured with a drone. It includes a few formerly incarcerated men, as well as victims. They came together to paste a monumental image composed of 338 individual strips of paper. A few years ago I started a journey called “Can Art Change the World?” It is still an open question. And with this project, I want to raise another question: “Can a man change?” Before answering yes or no, ask yourself a question: Have I changed? Did I make mistakes, apologize and amend for them? And if I haven’t, why haven’t I been able to?” – JR