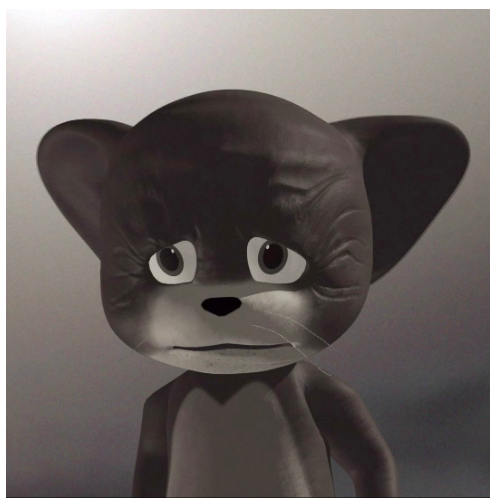

Rä di Martino | Poor Poor Jerry (2017) Courtesy of the artist and Cøpperfield, London & Snaporazverein, CH

British artist-curator Emma Cousin and writer-curator Paul Carey-Kent recently pulled together a choice of artist animations, thinking that the increasingly vibrant medium is especially suited to the online emphasis of the locked down art world of 2020. Three of them turned out to be represented by Galerie Ron Mandos, making the Amsterdam gallery ideal hosts. The cast is international, and to reflect that Tintype Gallery in London and Hamburg’s Blinkvideo have joined in with variations on the programme. You can see 13 films, each accompanied by a concise text explaining the appeal. In addition, Emma has a growing following for her lively Podcast Chats in Lockdown – and each week during August she will chat with one of the participating artists, adding to the material linked to the films.

British artist-curator Emma Cousin and writer-curator Paul Carey-Kent

Animation is an increasingly vibrant – indeed, animated – medium for artists, and enlivens a virtual platform. For Unstilled Life, the exhibition’s curators Paul Carey Kent and Emma Cousin selected 13 films that can relate to each other in a space that is activated, immediate and intimate – into people’s phones, screens and living rooms – even at a time of distancing.

More fundamentally, digitalisation, post-production and simulation have thoroughly undermined the indexical relationship of film to its origin in time, as a succession of moments preserved. Animation might be seen as more honest. There’s no disguising its source in imagination. Artists can create worlds which stem not from representation, but from freely extending their particular languages and concerns. It follows that these are not technically-driven films: the art comes first, and that’s often served best by quite simple approaches. We have chosen films in which artists bring their interests to life in this way, allowing them to add movement, time, words and sound to what is conventionally available to, for example, the painter or sculptor.

A considerable formal variety stems from the artists’ different underlying languages. Film has its relevance – Zbigniew Rybczynski trained as a painter first but went on to study cinematography at the world-renowned Lodz Film School, and Hans op de Beeck’s paintings are knowingly cinematic. Yet we may see the primary influences as painting (Jacco Olivier), drawing (Edwina Ashton, Erkka Nissinen, Markus Vater) or the interaction of painting and drawing in watercolour or illustration (Emma Talbot, Hans op de Beeck, Run Wrake). And sculpture (Djurberg & Berg, Levi van Veluw), theatre (Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley) and cartoons (Andy Holden, Rä di Martino) are also in play.

Rä di Martino | Poor Poor Jerry (2017) Courtesy of the artist and Cøpperfield, London & Snaporazverein, CH

The content of the animations is equally varied, but the themes of time’s passage, possible futures, and the contrast between the visceral and the cerebral can be traced. Moreover, the artists do typically use humour as a means to address serious issues. The two oldest films – whose creators were not primarily positioning themselves as artists, but whose work is relevant to current art production – set the tone: Rybczynski pushes farce to an extreme which captures how people may not connect in life, and Wrake comically conjoins objects with their words in a gleefully dark version of a children’s reading book. Social norms are questioned through di Martino’s exploration of the cinematic language of love, Nissinen’s satire on how reality is depicted in the media and Kelley & Kelley’s jarringly rhymed examination of suicide. Vater, Ashton, Holden and Djurberg take a more quizzical approach. Others may seem to play it straighter, but there’s an ingenious wit to how the material is marshalled by Van Veluw, Op de Beeck, Olivier and Talbot, even though their films are more sublime than comic.

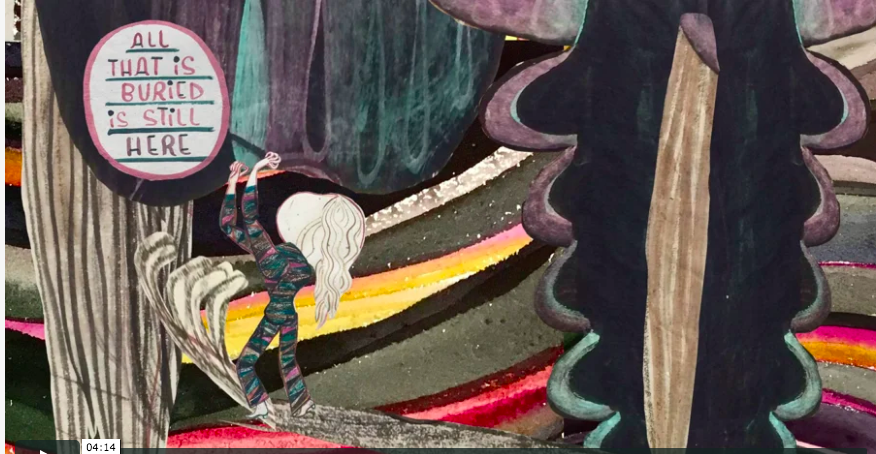

Emma Talbot | All that is buried (2020) Courtesy of the artist

Animation feels particularly appropriate in our current oddly stilled circumstances. Only Talbot’s work was made during the coronavirus lockdown, but the crisis has pointed up various underlying tendencies – so it’s not surprising that several of the films can be related to it. Rybczynski’s 36 characters are distanced even as they occupy the same small room. Travel serves only to make Ashton’s Mr Panz wonder if he should have stayed in his own garden. Night is a time of melancholically tinged isolation in Op de Beeck’s film. Following serial bifurcations, Vater’s worm only ever meets itself. Nissinen’s question ‘What is Community?’ takes on a different infection in a virtual context. Covid-19 has challenged the cohesion, echoing van Veluw, of our systems. And many of the artists ask – as we all do so urgently in 2020 – where should the world go next?

WATCH here now: ronmandos.nl/viewing_room/unstilled-life-artist-animations-1980-2020/