Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert gallery are showing the first of a series of three exhibitions honouring Eduardo Paolozzi. Titled ‘Hollow Gods’, this first show presents a selection of artworks completed in the first 15 years of Paolozzi’s career. In collaboration with the Paolozzi Foundation, the exhibition is curated by Dr Judith Collins – a former senior curator at Tate, and author of the most recent monograph on the artist, and of the forthcoming catalogue raisonné of his sculptures. The exhibition marks the first in a chronological series of Paolozzi shows that Collins will curate at the gallery in the coming years.

Eduardo Paolozzi, Untitled (1948). Collage, 14 1?2 x 9 1?2 inches.

Eduardo Paolozzi, Untitled (1948). Collage, 14 1?2 x 9 1?2 inches.

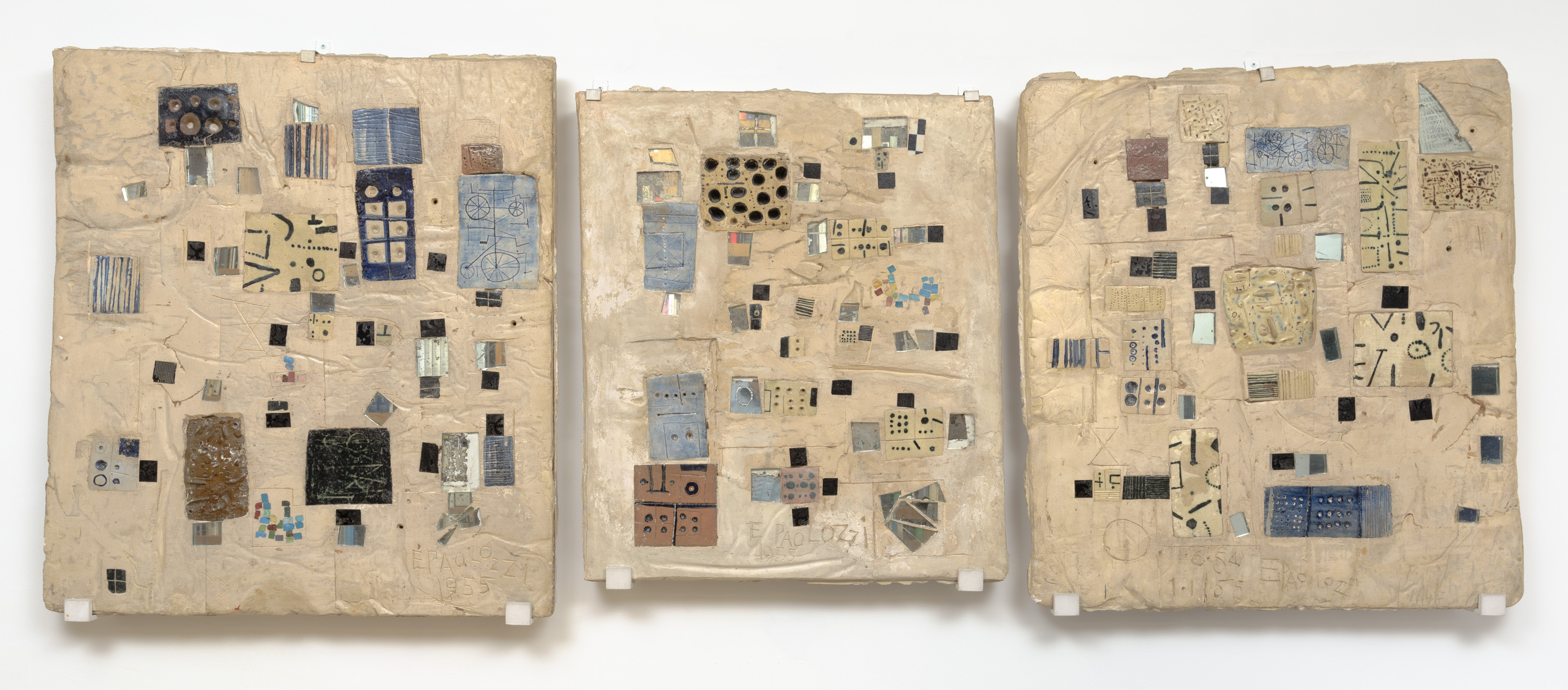

This cycle of exhibition, spanning the entire career-period of the artist, celebrates Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert’s newly announced representation of the artist’s estate– an incredible achievement, seen that Paolozzi never really had a dealer throughout his life. This first show includes 18 sculptures, three plaster reliefs and 15 works on paper, among them major works that have not been exhibited for decades, including the magisterial St Sebastian IV, and three large plaster reliefs from 1954-55 – once owned by Gabrielle Keiller, Paolozzi’s main patron in the 1950s.

Eduardo Paolozzi, Abstract Relief (1954-5, left & 1955 centre and right). Plaster, ceramic and mixed media.

Paolozzi, Scottish-born of Italian parents, studied at Edinburgh College of Art (1942-43), and at the Slade School of Fine Art (1944-47). Already as a student he gathered around himself a series of prominent critics and intellectuals in the art world. His first one-man show (of drawings) was at the Mayor Gallery in London while still a student. With the proceeds he moved to Paris, where he associated with the likes of Giacometti, Arp, Léger, Brancusi and Braque.

Eduardo Paolozzi, Table Sculpture (Growth) (1949). Bronze, height 81.3cm.

Eduardo Paolozzi, Table Sculpture (Growth) (1949). Bronze, height 81.3cm.

The influence of the Dadaists and Surrealists is clearly visible, especially in the early works exhibited at Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert. How not to relate Paolozzi’s Paris Bird (1949) to Max Ernst’s favourite alter-ego, LopLop? Or Paolozzi’s Table Sculpture (Growth) (1949) to Giacometti’s surrealist objects? Not to mention the love of Dada for everything juxtaposed, mismatched and cross-referenced; something Paolozzi certainly brought into his own collages and prints. It must also be remembered the huge importance played by Jean Dubuffet and the French group fo the Art Brut. The similarities between Paolozzi’s sculptures and Dubuffet’s figures is equally remarkable; as is Dubuffet’s admiration for Joseph Conrad concept of “a mixture of familiarity and terror”.

Eduardo Paolozzi, St Sebastian IV (1957). Bronze, height 220cm.

Eduardo Paolozzi, St Sebastian IV (1957). Bronze, height 220cm.

Yet it goes without saying that Paolozzi was not merely copying. Actually, he was not copying at all. As with everything, art is often the result of a lived past. Paolozzi started hoarding things as a child, when he would go into his father shop and pick up cigarette boxes, tickets, cards of cars, film posters… collecting them all together in his notebooks. Secondly, Paolozzi had a real obsession with the human form, which he only eluded from his creations when the pages where crammed with geometries and hallucinatory images.

With the endless inventiveness of Paolozzi, the human body entered in a cycle of cross referenced from a variety of sources. One day it was the broken fragment of a Greek statue, interested excatly in its been incomplete and ‘flawed’, as humans can only ever be– a hollow god. The human figure could also acquire a more playful tone, as in the many collages depicting everyday mundanity (which nevertheless enclose a certain nostalgia and depict the woman as an imprisoned figure into a patriarchal world of modern machine and domestic requirements).

Eduardo Paolozzi, Small Monument (1956). Bronze, height 33cm.

Eduardo Paolozzi, Small Monument (1956). Bronze, height 33cm.

It is with Paolozzi’s sculptures, so incredibly juxtaposed at the gallery with his works on paper, that the human being acquires the greatest drama; and reality. Produced with the lost wax technique (already favoured by many Surrealists), they are, indeed, hollowed sculptures. As Dada had already made clear, in spite of all the technological and industrial development of those days, the only concrete thing that the wars had brought was desctruction, and death. In the face of innovation, it was annihilation that was on the mind of people. As a response, or maybe stimulated by this atmosphere, Paolozzi’s sculptures are visually and physically decrepit, destructed, defaced.

Eduardo Paolozzi, Figure with Raised Arm (1955). Bronze, height 46cm.

Eduardo Paolozzi, Figure with Raised Arm (1955). Bronze, height 46cm.

Even more, these sculptures, are not only the result of a solidified material, shaped somehow like a body. Paolozzi’s (very personal) technique incorporated into the very structure of these bronze bodies found-objects, such as ‘Dismembered lock. Toy frog. Rubber dragon. Toy camera. Assorted wheels and electrical parts. Clock parts. Broken comb. Bent fork. Various unidentified objects. Parts of a radio. …’ as he professed in a lecture at the Institute of Contemporary Art. These ‘trouvailles’ were pressed into a clay or plaster bed and then removed, leaving a negative impression.

Image Credit: Eduardo Paolozzi: Hollow Gods at Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert, London, 17 October – 13 December 2019, hh-h.com. All images are copyright of Paolozzi Foundation and courtesy of Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert.

Eduardo Paolozzi: Hollow Gods

Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert, 38 Bury Street, St James’s, London SW1Y 6BB

17 October – 13 December 2019

Monday-Friday, 10am – 6pm Saturday-Sunday, Closed