2 ¼’ closed on 1st June 2019. The show was the first presentation of William Eggleston’s work at the Gallery’s London address and Eggleston’s second solo exhibition since joining David Zwirner in 2016. The show included 17 photographs all taken in 1977.

Photographer William Eggleston poses during a photocall for his new exhibition “2 1/4” at David Zwirner on April 10, 2019 in London, England.

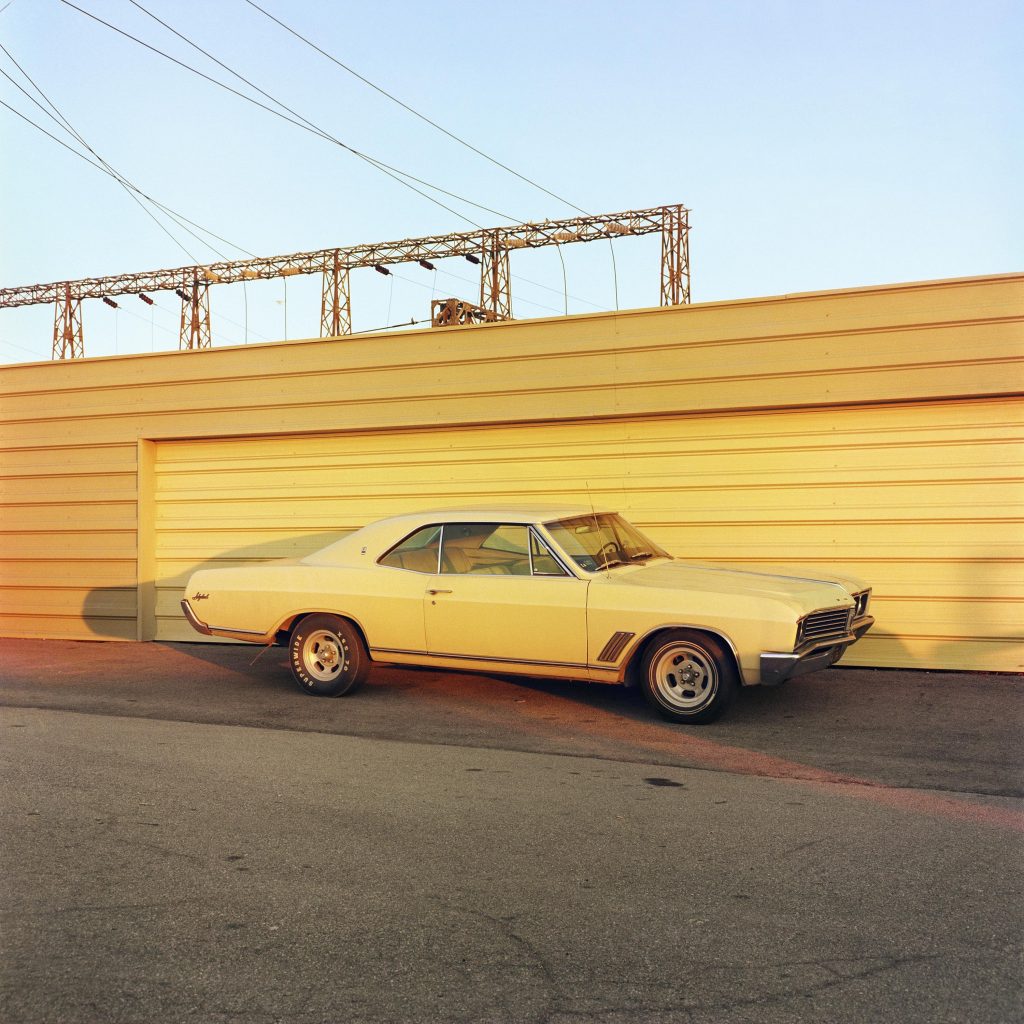

In the honey light of California William Eggleston’s photographs, quite literally, shine a spot-light on the ordinary, the everyday, the commonplace. Street corners, signs and cars are enlarged to 50 ½ x 50 ½ inches which gives a sense of monumentality to such everyday sights. Even a crumpled can or scrunched up piece of newspaper abandoned on a street corner is magnified and given an important compositional status. I came out of the exhibition feeling like I had been given new eyes, eyes opened to notice the usually unnoticeable.

In one sense the magnification of the everyday is a quality that gives Eggelston’s photographs a timelessness. The uniform ‘untitled’ title of each photograph added to this sense of timelessness and dislocation. The locations are liminal, the side of the road stops that are ubiquitous to most of America’s mid-west. Yet, the focus on cars instilled in me a strange awareness of how much time lay between 1977 and 2019. I wondered if these photographs were taken today if they would be received as a loud environmental appeal and a political statement. Attitudes to cars have changed enormously since 1977.

In 1977 a car in America was a symbol of freedom and of the ‘American Dream’. The wide bonnets of a Cadillac promised access to the open highway. The car provided agency. The car gave man the time and space to to lose oneself, or find and define oneself. The automobile could propel you through the land to a new place and a new life. Similarly, the camera was another machine full of potential. Both car and camera were machines of hope for the future. Eggleston is clearly aware of this and masterly handling of the camera, shooting in a two-and-one-quarter-inch medium-format camera (this detail being the inspiration for the show’s title). Through this medium Eggleston transfigured the car into a monumental artwork. The contours of the bonnet, lights and handles are given a sculptural presence in the American landscape. Although Eggleston’s compositions play on chance encounters their stillness has a dramatic theatricality, like a stage-set ready and waiting for the actors to bring the scene to life.

This stillness opens Eggleston’s photographs to post-apocalyptic interpretations. This interpretation has only gained weight in the last five years with the growing global awareness of climate change. Eggleston’s favourite motif the car has gained a less hopeful symbolic status than in 1977. Today, cars have become symbols of the worlds when the growing awareness of the damage car emissions reek on the atmosphere, the tension fuel consumption puts on international relationships. In London diesel and petrol cars might be banned from the city by 2020. Eggleston explained: “Often people as what I’m photographing, which is a hard question to answer. And the best what I’ve come up with is just say – Life today”. David Zwirner’s show left the viewer wondering what ‘Life today’ looks like in comparison to Eggleston’s photographs on 1977’s America