ALMA ZEVI gallery in Venice presents Alain Baczynsky’s new exhibition HATUFIM a project Baczynsky has been working on for six years. A simple design, and a relatively small number of works reveal rich layers of meaning.

The artist started HATUFIM back in 2013, and just completed it for this Venice exhibition. The show comprises a series of eight photographic diptychs, which pair together the portrait of a person, alongside a self-portrait by Baczynsky. The majority of the photos have been shot by Baczynsky in his Jerusalem studio, between 2015 – 2017, showing the sitter against the typically white studio wall. Only two photos, the starting point of the exhibition, have been taken from archival documents, and have been preserved in black and white.

All photos, both those of the sitters, and Baczynsky’s recurring self-portrait, are carefully constructed. They all follow the strict parameters associated with a passport or official identity photographs. Sitters and photographer are shown directly facing the viewer, in front of a bright, white wall. The difference is in that the artist’s eyes never appear. His self-portrait, in fact, has been subjected to the same manipulation eight times. Baczynsky (digitally) cut the eyes, some times even the eyebrows, of the facing portrait and pasted them onto his own. His face, repeated for eight-times alongside almost identical characteristics, always assumes the gaze of his neighbour.

The exhibition is itself carefully designed to create a constant shift between opposing poles. Alternatively, the sitters enter into their antipodes dimension. There is a constant tension between self and other, in which ‘otherness,’ for once, does not acquire the problematic ‘primitivist’/Eurocentric connotations. Here, the other is used to establish an empathic connection between Baczynsky and its poser. Interviewing the artist, he really emphasized his intention as one emerging from an insatiable curiosity:

It’s about empathy. I want to try and understand the world with other people’s eyes. I want to see through their eyes.

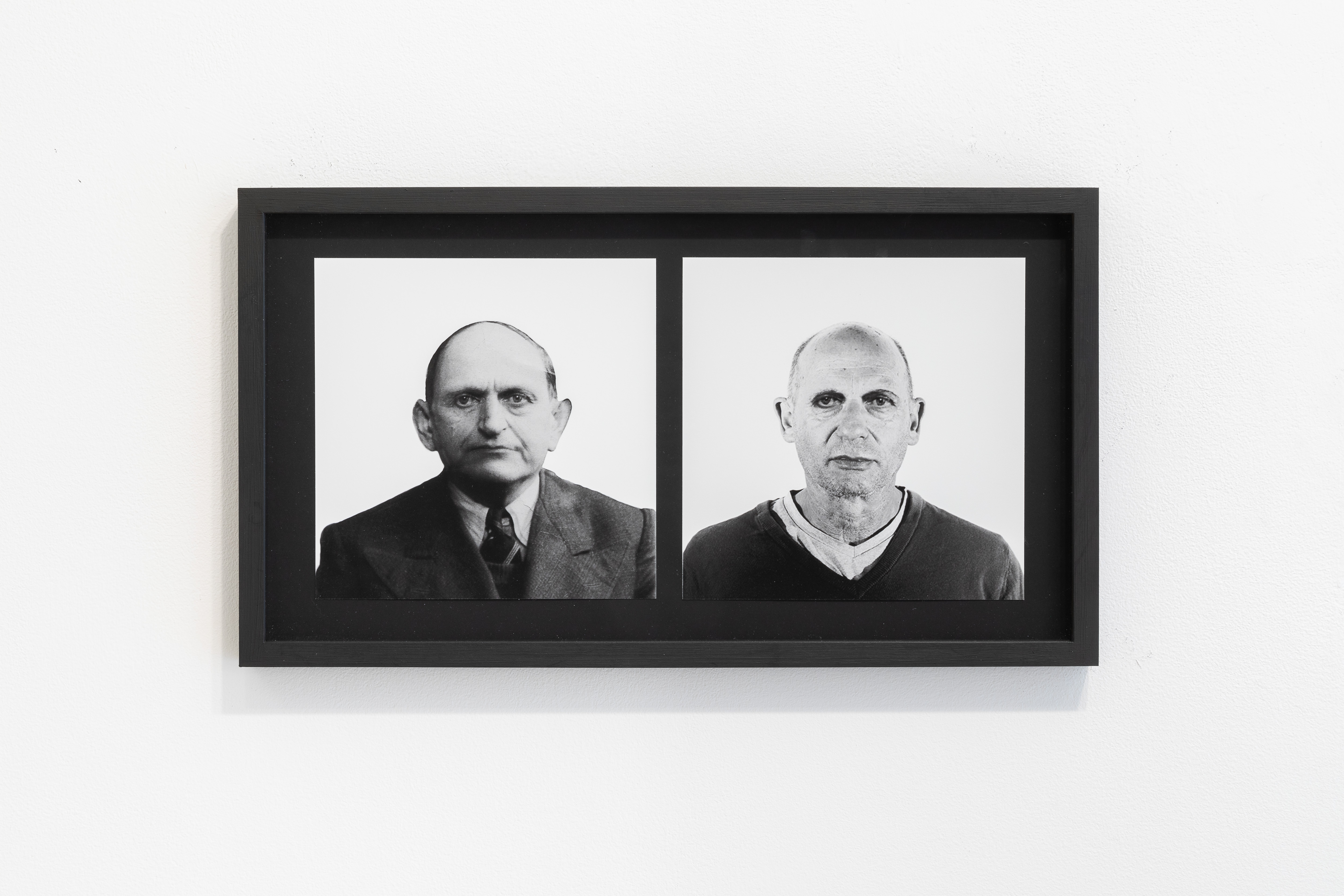

Aba Baczynsky and Alain Baczynsky

Aba Baczynsky and Alain Baczynsky

None of the sitters is casual. All of the people photographed are linked to Baczynsky in some way. Either because of their political situation or due to familial links, they already have some sort of empathic relation with the artist. The narrative starts from two pair of photos — the only ones in black and white, the only ones not taken by Baczynsky in a studio, the only ones on the left-hand side wall of ALMA ZEVI.

The first couple juxtaposes Alain Baczynsky with Aba Baczynsky, his grandfather. He was a very important person for the artist, and yet he claims to know very little about him. Baczynsky never met him, and his family was quite reluctant to talk about him. The grandfather died during the second World Was, deported in Auschwitz in 1942. Here, the first dichotomy takes place. On the right side of the grandfather/grandson pair, Baczynsky placed his self-portrait close to that of Rudolf Höss. He was an infamous Nazi SS, responsible for the death of millions of people in the Nazi German concentration camp in occupied Poland, possibly even of the artist’s grandfather. After the Nuremberg trials he was sentenced to death, himself in Auschwitz, 5 years after Aba Baczynsky’s death there.

Rudolf Höss and Alain Baczynsky

Rudolf Höss and Alain Baczynsky

Two people, starting from diametrically opposite sides, end with, nearly, the same faith. There is no comparison between dying after the camps’ tortures and deprivations and ending your life after a death sentence. This photographic pair creates a potent juxtaposition, leaving the viewer wonder if there is a sort of distant redemption hinted at or just a frank display of pain and revenge.

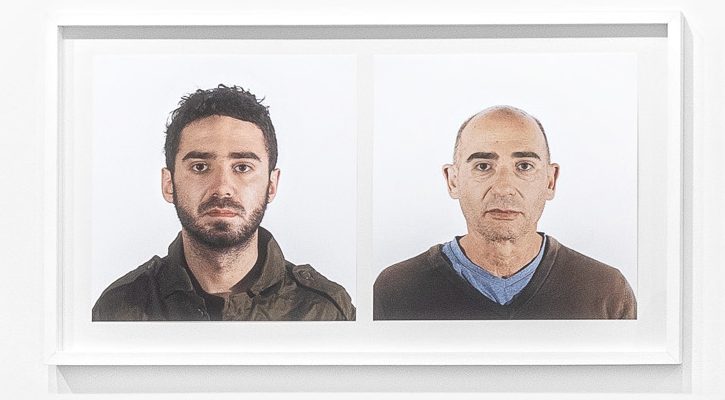

Israeli man and Alain Baczynsky

Israeli man and Alain Baczynsky

This pair leads to one associating a twenty-year old Israeli student with an even younger Palestinian. The Israeli was forced to join the military units in Gaza twice. The first one was during the compulsory military service to which anyone is called-up to, between the ages of 18 and 21. After studying architecture at university, he was forced into the military service once again. On the other hand, we have a Palestinian active fighter, who regularly opposes the Israeli forces during any clash and dispute. His higher level of violent determination is paradoxically concealed in his portrait. His face is in fact almost completely covered, leaving outside only the eyes, central to the exhibition. Curiously, it all happened by chance, as if he felt automatically compelled to leave his gaze to the photographer and the future beholders.

Palestinian man and Alain Baczynsky

Palestinian man and Alain Baczynsky

While we might be tempted to delve further into who’s more to blame, I would leave these comments aside. If there is one thing that armed conflicts can teach us is that they leave death and despair on both sides of the fence, and that they only generate more and more revenge desires. These Israeli-Palestinian diptychs thematically link to the concentration camp victim versus executioner-turned-executed. Yet, here we have two incredibly young men, whom at the age of twenty years old have been already living through death and destruction all their life. Baczynsky’s curiosity knows no limits. So he chose to see the world even through these sabotaged eyes.

In between the two diptychs with the fighters, we have two new dyads, operating on a different panorama. A nonagenarian Palestinian man symbolically plays with a one-week-old baby. The older figure is a former guide in Palestine. He used to travel through the path connecting Bethlehem with Beirut, before it 1948 when it became impossible to do so. Not only has he seen and experienced much more than the toddler. He also looked at, and vividly remembers, some places no one will ever be able to see again (if not Baczynsky, kindly borrowing his eyes and memories for a while).

Blind Ethipian, Palestinian, nonagenarian, Israeli and new-born, all paired up with Alain Baczynsky

Blind Ethipian, Palestinian, nonagenarian, Israeli and new-born, all paired up with Alain Baczynsky

Standing apparently without a pair, and visually opening up the series on the right wall of the gallery, is the portrait of a man of Ethiopian origins. His eyes, now blind, are pointing upwards, signed by marked capillars. His vision of the world, once lucid, is now rendered nebulous, unattainable. His visual memory is worth exploring nonetheless, hence Baczynsky’s substitution of his eyes with the blind ones. Yet, nothing can be as blinding and impossible to decipher than your daughter’s expression. At least this is what the artist thinks. No matter how much he tries, his daughter remains ‘the bigger mystery’. But he did attempt to understand her. After all, children at first look at the world through their parents’ eyes. But it comes a moment when they acquire their own independence, which comes most of the time with a disconnection with their mothers and dads. The last diptych comes now into play. It poses side by side Baczynsky’s daughter and himself, expectedly with her long-lashed eyes.

Hatufim was not the first time that the artist engaged with his self-image. In 1979, upon visiting a psychoanalyst for 3 years, he decided to shot a photo of himself after each session. As in a Surrealist automatism, quite on point seen the shared interest in psychoanalysis, the self-portraits acted as a “visual psychoanalytical process.” An ‘appointment’ with a photo-booth followed all appointments with the psychoanalyst. Inside of it, in isolation and almost contemplation, he mentally reenacted the session, annotating his thoughts on the back of the print. In the three years, Baczynskzy gathered together 242 self-portraits/automatic memories. This 1979-1981 series, Regardez, il va peut-être se passer quelque chose, was acquired by the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 2012.

The work presented at ALMA ZEVI adds a new level to this unconscious language. Baczynsky’s portrait is no longer the medium between his own unconscious mind, and a tangible translation of it. He creates a collective unconscious, instead. By enacting his own blinding, Baczynsky allows for unsettling shifts of identity. Psychoanalysis can be read into the work, although the artist did not necessarily intended to do so. The Oedipus myth, in fact, pivotal in Sigmund Freud’s theories, saw the principal character casting off his eyes. As an act of both punishment, and hopeless redemption, the king Oedipus remains blinded by his own fate. In Freud, the myth takes on sexual (typically Freudian) connotations. It relates to the king of Thebes’s incestual relationship with his mother, which, according to the psychoanalyst, is a primal drive common to all humankind. In Baczynsky the sexual linings leave way to a personal research.

Baczynsky’s portraits do not take up the Freudian taboo-like references. They keep metamorphosing into what acquires deep social relevance. Baczynsky’s eye, in fact, subsequently are superimposed by the identities of a Palestinian refugee, a young Israeli soldier, a new born baby, a nonagenarian Palestinian man, and a blind Ethiopian immigrant.

Through the repetitiveness of the motif of the artist’s self-portrait combined with the variation

of the other subjects’ gazes the viewer becomes aware of the uncanny juxtapositions at play. If the style and format adopted by Baczynsky recalls a certain tradition of the photographic portrait (traced back to August Sander’s People of the 20th Century and in its legacy on the Düsseldorf school in the 1990s), it also disrupts it. What is usually used as the referent for the single individual, its official passport photo, is here challenged by an unstable doppelgänger.

In Hebrew, Hatufim means ‘kidnapped’ or ‘abductee’ – words that in their etymologies refer to a state where one is ‘pulled or led away’. In this case, the title may refer to the use of identification photos for police and trials ends. Even more, it points to the captive status of the human mind, gripped by repressive norms and oppressive realities.

As Inès de Bordas commented,

The experience of looking at Hatufim is interrupted by the realization of a double presence, of a breach in the representation of the artist’s identity – one that challenges the viewer to look at portraiture anew.

Alain Baczynsky, HATUFIM ALMA ZEVI, Venice – San Marco 3357, Salizzada San Samuele, 30124 Until 20 April 2019