Fred Romero / Flickr, CC BY-SA

Anna Francis, Staffordshire University

The value of culture in regenerating cities has long been recognised. Sometimes this happens centrally, whether via the commissioning of high profile public artworks, or the rebranding of city areas as cultural quarters. But in many cities, culture led redevelopment occurs organically.

Artists, generally on relatively low incomes, move to areas of the city where rents are affordable. The presence of the artists make the area interesting, leading to more interest in property in the area, and ultimately, seeing the area develop. Sadly, this process usually ends with the artists having to move on, as rents increase.

Councils and developers are now attempting to emulate these organic, artist-led processes, by purposefully moving artists in to areas of cities which they wish to see developed. The presence of the artists in this new contrived context is conceived, from the start, as an interim measure. In the worst cases, it is intended as a distraction from the dirty business of clearance and demolition. This has been described as “a cleansing process in which the artists moving into a burgeoning area were treated by developers as a form of regenerative detergent”. Given such language, it is perhaps unsurprising that the artists involved in these schemes are finding their work labelled “artwash”.

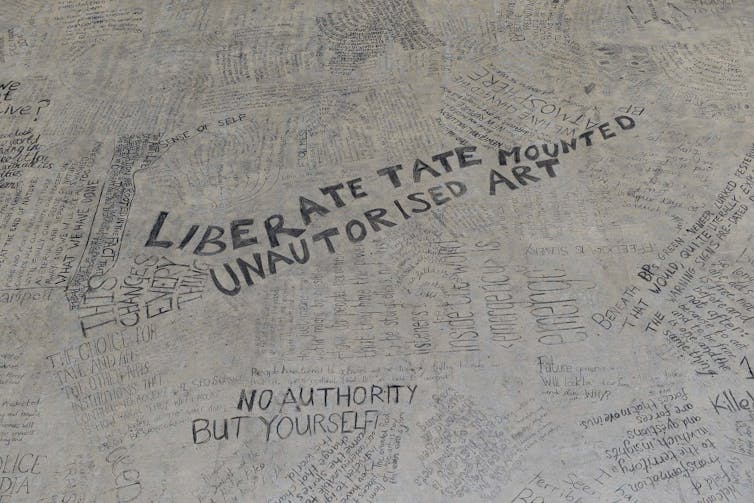

“Artwash” is a relatively new term. It seems to have first been used to critique corporate sponsorship of the arts: large companies establishing a relationship with a cultural venue with the aim of improving their reputation. BP, for example, has long sponsored the Tate galleries in London, something that has prompted much protest. A spokesperson from one such protest group, Liberate Tate, explains: “Artwash is the process whereby a company buys advertising space within a gallery in order to cover up negative public image.”

slowkodachrome/flickr, CC BY

Naming and shaming

But now accusations of artwashing are reaching beyond corporate sponsorship to apply to individual artists in local communities. A new practice of naming and shaming artists working within the context of gentrification, particularly in larger cities where large scale development is taking place, has seen some artists working in social contexts accused of being “artwashing gentrifiers”. In extreme cases, galleries and artists are being run out of town.

These recent, predominantly online attacks on artists and arts organisations have seen the artists being named as responsible within the process. At best they are labelled as naive to the developer’s game, and at worst complicit.

This practice is becoming particularly controversial in London because new development and fast gentrification is reaching an all time high, pushing more and more local populations out of their homes. Questions around who is really to blame for such a damaging form of gentrification are becoming more urgent. And more ugly.

Ewan Munro / Flickr, CC BY-SA

The emerging animosity towards artists has led to a number of groups being set up in order to target artists working within regeneration contexts. The groups include activists, but in some cases, artists and academics are behind the campaigns, which use Twitter and other online platforms to voice dissent.

Interestingly, even artists aiming to question the role of the arts within processes of regeneration are finding themselves targets of the online criticism. I experienced this first hand when delivering an art project in London earlier this year.

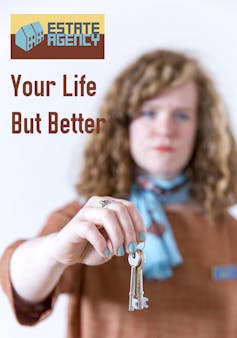

Estate Agency

The project, “Estate Agency”, involved a staged closure of London’s Campbell Works Art Space, to see it reopen as a fake estate agency displaying affordable property in Stoke-on-Trent. The project aimed to raise questions around the experience of many London based artists and arts organisations, who have been finding it ever more difficult to afford to remain in the capital.

The Stoke Newington area, where Campbell Works is based, has seen property prices rocketing in recent years. Over the course of the project we heard many stories about the loss of community and the devastating impact of gentrification on people’s lives and sense of self. The creeping processes of gentrification, which can happen gradually, are often difficult to pinpoint. We aimed to make these processes of change more visible, and to create a space to discuss issues raised.

Anna Francis, Author provided

The manner in which we did so was somewhat tongue-in-cheek. “#YourLifeButBetter” was blazoned on the “estate agency”, which reframed Stoke-on-Trent (a city which became known as Brexit Capital last year) as a viable place for artists to move to, with affordable housing and studio space on display. Stoke is bidding for City of Culture 2021, and as such, is actively courting a new future via arts and cultural activity.

The aim was to create a space to understand the role of art and artists in these challenging contexts. Using the language and imagery of developers and prospectors, the project also explored the experience of towns like Margate; where swathes of artists moving in have changed the cultural make up at an alarming speed.

In dealing with the thorny issue of culture-led development, we found ourselves under fire by online critics. They accused us of the very processes we were seeking to critique. Imagery and slogans from the project were taken up by online activists, who accused the project of artwashing gentrification. Their main objection was our use of irony in relation to a serious issue which is affecting people’s lives.

![]() In understanding the role that art and culture can have in changing places, it is now important to ask if what we are creating is of benefit to everyone concerned. Artists have a role to play in both questioning the processes of regeneration, but also, I believe, in supporting communities within these places to articulate their experience, and to advocate for their rights. Far from being an artwash, this can be a celebratory and cathartic activity – even if the outcome, eventually, is the same.

In understanding the role that art and culture can have in changing places, it is now important to ask if what we are creating is of benefit to everyone concerned. Artists have a role to play in both questioning the processes of regeneration, but also, I believe, in supporting communities within these places to articulate their experience, and to advocate for their rights. Far from being an artwash, this can be a celebratory and cathartic activity – even if the outcome, eventually, is the same.

Anna Francis, Associate Professor of Fine Art and Social Practice, Staffordshire University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.