The Jerome Project (My Loss), 2014 by Titus Kaphar. Photograph: Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

With eerie, welded sculptures, tar-coated gold panels and a menacing piano affixed to a tree, a set of black American artists is exploring the history of racially motivated violence in the US through a new exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum. The Legacy of Lynching: Confronting Racial Terror in America – now on view – traces the links between slavery, segregation and mass incarceration.

“There haven’t been any exhibits that try to present the perspective, reflections, and responses to lynching by survivors and victims,” explains Bryan Stevenson, a public-interest lawyer and the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative. In fact, this is the first time a major art museum has used lynching as the central theme of a show. (In 1935 the NAACP organized an exhibit of illustrations and prints about lynching at New York’s Arthur U Newton gallery.)

James Baldwin once wrote, “Not everything that is faced can be changed; but nothing can be changed until it is faced,” and this quote acts as a sobering opener to the exhibit that’s later echoed in Glenn Ligon’s text-based works, which pay homage to Baldwin. Organized in conjunction with the EJI, the show concretizes a detailed digital report on lynchings with an interactive map, audio recordings and original photographs.

To listen to disturbing testimonials and see emotionally freighted imagery is to learn how lynching was used as tool of racial control – and understand how it set a precedent for the current epidemic of police brutality and mass incarceration. “Lynching had a profound impact on the demographic geography of this nation,” Stevenson explains. “It forced millions of black people to flee the American south as refugees and exiles. It established a shameful legacy of violence and torture in hundreds of communities across this nation that have largely failed to acknowledge this history.”

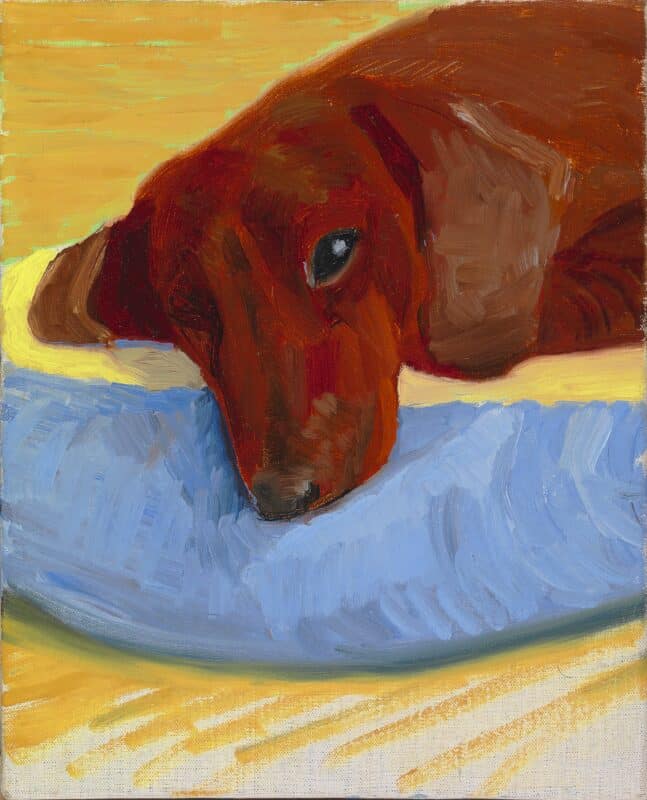

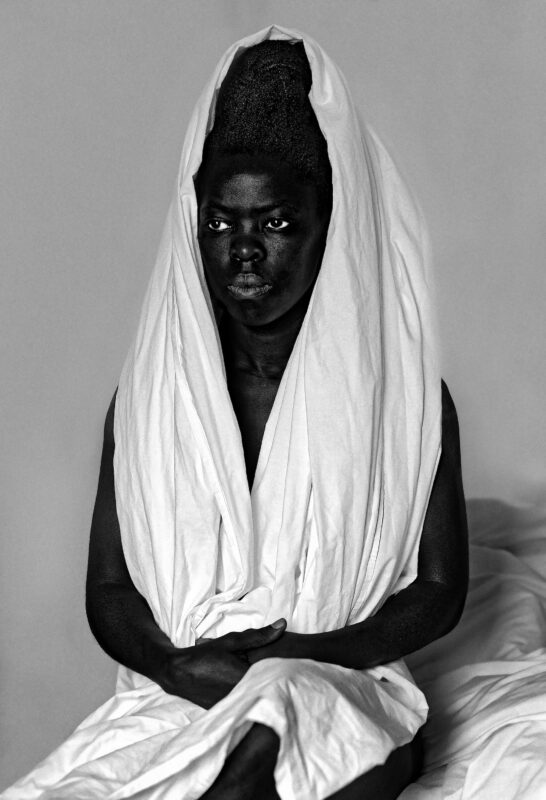

Among the pieces pulled from the museum’s permanent collection are works by Sanford Biggers, Mark Bradford, Elizabeth Catlett, Melvin Edwards, Kara Walker, Theaster Gates, Rashid Johnson, Titus Kaphar, Jacob Lawrence and Glenn Ligon. On view in a clear lacquer case, Kara Walker’s laser-cut steel sculpture of a lynching scene has a particular emotional resonance. For Mark Bradford’s lithograph Untitled, a series of shapes have been printed to represent, in combination, nooses – transforming an abstract pattern into a haunting tapestry of pain.

In an essay for Harper’s, novelist and essayist Zadie Smith discussed the movie Get Out as proof of a “moment of resurgent black consciousness.” Writer and director Jordan Peele offers a vision of present-day America that is the “opposite of post-black or post-racial,” she wrote. “[He] reveals race as the fundamental American lens through which everything is seen.”

Similarly, this exhibit addresses racial persecution and inherited trauma with a directness that demands an honest reckoning with – especially from its white visitors. The organizers have not brushed over the history of lynching in broad strokes but rather have framed it with specific and harrowing details. In one testimonial, the grandson of a survivor reads a newspaper clipping from 1919 about his family’s friend, who was shot but kept alive overnight in a doctor’s office so that he could be publicly lynched the following day. The front page headline in the Mississippi Daily News is sparse and sobering: “John Hartfield Will Be Lynched by Ellisville Mob at 5’O Clock This Afternoon.”

As assistant curator Sara Softness tells the Guardian, “This work requires telling the truth in public spaces, signaling that this pain matters, and saying never again. Similar to Holocaust memorials in Germany or the Apartheid museum in South Africa,” The Legacy of Lynching memorializes victims and their families, while challenging complacency in the face of injustice.

Next spring EJI will open a six-acre memorial in Montgomery, Alabama, to honor the lives of more than 4,000 African-American lynched from 1877 to 1950 – whose names will be engraved on a series of columns. The organization has asked that counties claim columns and install them at the original sites where the lynching took place. At least 33 lynchings were reported in Florida’s Orange County, 40 in Illinois’ St. Clair County and 48 in Mississippi’s Leflore County. (In the state of Mississippi alone, 654 lynchings have been documented for this 73-year span.)

Unlike the recent Whitney biennial, which included Dana Schutz’s controversial painting of Emmett Till’s brutalized body, the Brooklyn Museum has steered clear of photographs or illustrations that show explicit bodily violence. As Softness explains, “The artworks on view allude to trauma, loss and pain in non-explicit ways, offering personal, poetic and symbolic perspectives.”

- The Legacy of Lynching: Confronting Racial Terror in America will be at the Brooklyn Museum until 3 September

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.