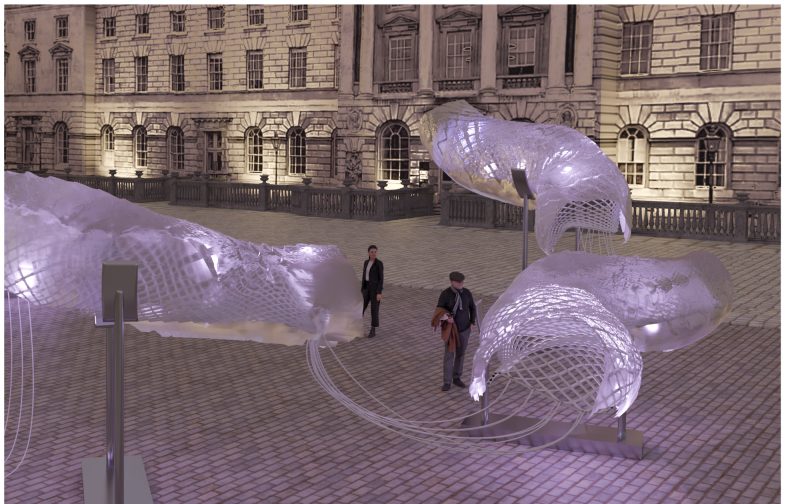

‘Like saplings in a window box’: Giacometti sculptures at Tate Modern. Photograph: Joe Humphrys © Tate

There is a figure no bigger than a pin halfway through this colossal retrospective. It emerges from a plinth the size of a frugal chunk of cheddar. You could pocket the whole object without difficulty; indeed Giacometti (1901-66) once returned from his native Switzerland to Paris with all the sculptures he had made through the second world war neatly contained in six matchboxes. No matter how tall or broad he wanted them to be, the artist said, each figure just kept getting smaller and smaller.

The size and shape of Giacometti’s sculptures is both intensely famous and surpassingly strange. That is the lesson of this show. Poorly lit, tactlessly displayed and about as overcrowded as a Giacometti show never should be – 250 works, densely contextualised with drawings, memorabilia and even ornamental floor lamps – it nonetheless gives a sense of the artist in all his prodigious variety, from the pinheads to the striding giants, the thin men to the rows of tapering women, rigid but helpless on their stands. Uniquely alone, and yet palpably connected, they amount to a new race of sculpture.

The show opens with a head-on confrontation. A jostle of Giacomettis – contradiction in terms – stands waiting in the first gallery: busts on white pedestals, intently upright, oncoming, eye to staring eye. They run from brilliantly realistic depictions of his family in the 1920s, to plaster heads, pancake-flattened and painted, muckle post-cubist busts and a miniature much-worked clay of Simone de Beauvoir from 1946. A riffle through Giacometti’s youth and growing maturity, it shows him as tender, quizzical, ever-changing, acute – an artist at least as protean as Picasso.

He falls in with the Paris surrealists. Here is that grotesque bronze, Woman With Her Throat Cut, a clatter of rachitic ribs and limbs violently splayed on the gallery floor. Reclining Woman Who Dreams is just a couple of undulating horizontals crossed with a spoon for a head, so the sleeper’s body is both bed and flowing dreams. In Point to the Eye, a tiny nub of head is menaced by a long shank of plaster, something like a tusk, very nearly jabbing it in the eye. But the little head resists, opening up as if to say “Don’t shoot”. It’s an inspiring Gandhiesque protest.

The surrealists chucked him out for heretical realism, but Giacometti was always on this side of humanity in any case. Look at the sequence of couples, loving and lightsome – women shaped like leaves, men like inverted hats – or the marvellous Gazing Head sculptures, each a flat parallelogram of coloured plaster or clay trying to see its way forward in life. Personality is all there in the almost imperceptibly varied tilts.

Although we know Giacometti’s works mainly in bronze – prolific and costly: his Man Pointing broke world records in 2015, selling for $141m – he preferred malleable media that could be modelled and inflected by hand over months and even years. His etiolated figures are all heavily worked, their substance pinched, pressed and extruded, rubbed and nubbled until, perhaps, they got longer or smaller – worn down as if by life.

Giacometti, ever eloquent, explained that the smallest of his sculptures was born of the desire to represent a memory of a friend seen from afar in Paris. Curatorial congestion at Tate Modern prevents the needful distance, so there’s no way of experiencing this optical effect; instead we cram in close to examine these vigilant figures bonded to their plinths. But the spell of estrangement remains. It is especially evident in the narrowest depictions, which are almost anamorphic: flat in profile, blade-thin from the front. Giacometti believed you could never retain the full face, and vice versa, when you moved to the profile.

How to see: how to capture what you see. Giacometti spoke of art as “the residue of vision”, and every work here feels like the essence, though sometimes the essence of a Giacometti. The artist could be repetitive. There are so many striding figures getting nowhere, held back by feet of clay; so many female forms ranged like saplings in a window box. A little portrait bust in grey plaster, however, all its anxious wrinkles and creases graphically crosshatched into the surface, is so precisely the embodiment of Giacometti sketch as to be the startling hybrid of sculpture and drawing.

And they have the quicksilver subtlety of drawings, these dark and linear forms that conflate contour, identity and dimension. It seems that everyone can be sculpted this way: round-faced Jean Genet, tip-nosed Madame Giacometti, turbanned De Beauvoir: themselves, but on the edge of exiguity. This was rather more apparent in the National Portrait Gallery’s 2015 show, which perfectly crystallised Giacometti’s art through the narrow prism of portraiture, than it is in this all-together-now throng, where figures are backed against partitions like shop-window dummies.

But this vast array includes many works that have never been seen here before, such as the Woman of Venice series, a stand of female sentinels, fragile, ethereal and yet gritty in their almost luminous plaster. Indeed one entire gallery is planted with strangers – a gaping, upturned head, a single giant leg taking a stride, an arm outflung, the fingers spread – so abrupt it seems to keep on gesturing madly in mid-air.

A Pinocchio, a shaman, a portrait of the Japanese philosopher Yanaihara seeming to disappear (like the drawings) into cross-legged meditation: how populous and varied the world was to Giacometti. There is even an extraordinary sculpture of a loping dog, getting along the back wall of the gallery, a fugitive critter, exhausted and emaciated but still pursuing a dog’s life. Some walk tall, some crumble, some have only half a head and no body at all. But always there is this magnificent staying power.

• Giacometti is at Tate Modern, London until 10 September

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.