Digital artist Kate Cooper presents a new body of work as part of her first solo exhibition in the UK at VITRINE in London entitled Ways to scale. Cooper’s artistic practice, consisting largely of computer-generated (CG) imagery in both video and digital print form, critiques the ubiquity of the flawless CG female in our consumer capitalist society and the labour used to create these glossy digital bodies that are almost obligatory in today’s mass-advertising campaigns.

Since winning the Ernst Schering Foundation Art Award in 2014, which granted her a solo show at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin that same year, her work has been exhibited extensively across Europe and the US. This Liverpool native now divides her time between London and Amsterdam where she is currently undertaking an artist residency at the Rijksakademie. In addition to her own practice, Cooper is also the director and co-founder of the London-based artist-run organisation, Auto Italia South East, that commissions and produces new work in direct collaboration with emerging artists.

On the occasion of her solo project at VITRINE (28 April – 18 June 2017), Marcelle Joseph talks to Cooper about hypercapitalism, feminism and the digital body.

Congratulations on your latest solo project in London! I assume that it is a unique and trying experience for an artist to make work for a space enclosed entirely behind glass windows that can only be viewed from the surrounding external public space. Saying that, it seems like the perfect locus for your work. When I approached Bermondsey Square, I was confused – am I looking at an off-site avant-garde window display for Harvey Nichols? Is this slippage important to this new work?

My work over the past few years has been focused on interrogating my relationship to these hyper-commercialised images, my desire for them but also their inherent violence – through the presentation of perfect bodies that perhaps exist beyond the realms of reality for human capacity. I’m interested in exploring how these CGI models can function and what new forms of agency these images might provide: can they create new possibilities or politics for our physical bodies? I’m interested in how they create their own realities through the production of this fictional space and what possibilities these might offer. Sometimes, I feel that the aesthetics related to these images are misread; we are all pretty tuned into these languages and what they can do, and I’m interested in how we might ‘read’ these images – and the embedded infrastructure they might contain – through their production and distribution.

What was interesting with this installation was this combination of the work and where it is situated within such a public space. This space like many others is a marker of gentrification within London and has a particular aesthetic. VITRINE Gallery is next door to a supermarket, cinema and luxury apartments, which means these CG figures I’m working with perform this double function, being at once totally readable as models of selling ideas, products even but also as faceless and unreadable. This slipperiness is interesting to me – to want a possibility to exist with a particular coded space but also want to integrate that. I think the complete removal of people from lower socially economic backgrounds in this area really speaks to the state of the city at the moment. I was thinking of my work within this highly gentrified space and how it is coded; what this form of presentation does and can do here and how it might be read or misread.

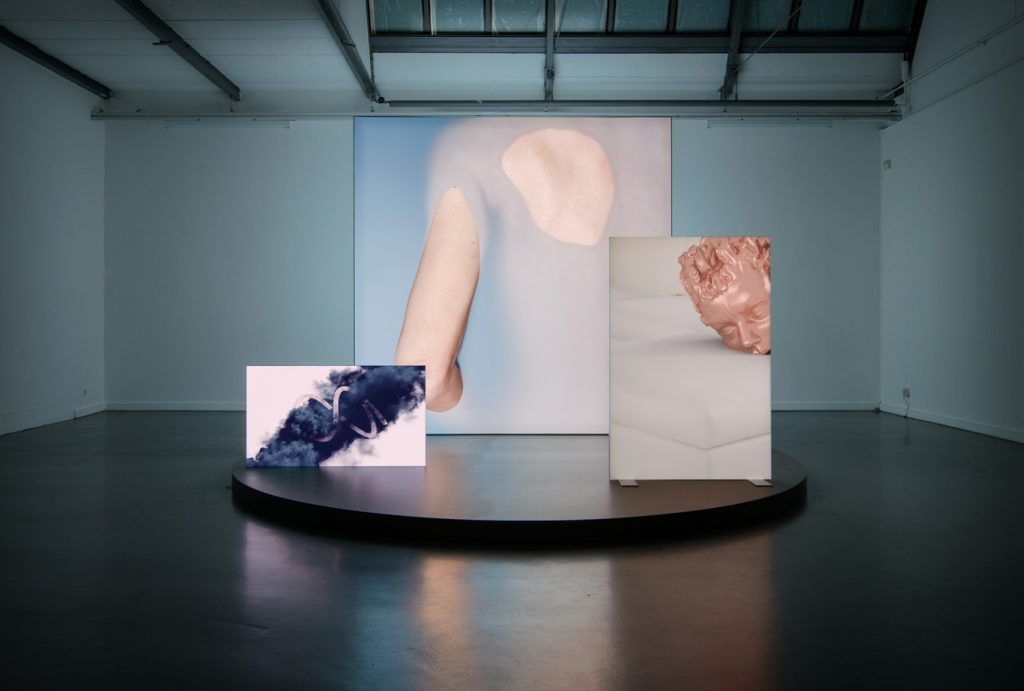

Your new show consists of one work – a billboard of sorts, depicting various jellyfish, a seated woman garbed all in white with her head cropped out of the picture plane and another disembodied flayed figure holding a vacuum cleaner. All rendered using hyperreal CGI technology. Could you talk me through the different pictorial elements and what they represent?

I’m kind of uninterested in the traditional ways we ‘read’ work. This whole part of my practice is looking at how things have shifted and how this material actually works in the world, which includes considering how my work can be misread.

I’m more concerned with the mechanics of how the image comes to be – how it works and what it does. For me, the process of ‘reading’ becomes redundant when we think about how machines read and communicate through images and code– it’s beyond how we relate to things and creates new ways for these to develop a language and go beyond our symbolic, basic understanding. I’m interested in considering more radical reproaches to reading images and how they might perform. I always think about the approach to my work as a hacking and how to tackle these things in new ways – how to work with the material that surrounds you. I want to find a freedom in exploiting that. The speed in which images are distributed means we need to shift from reading them symbolically or attempting to discern inherent meaning to thinking more about what they do and the speed by which this happens. This might not all be taking place in my work here but it’s definitely how I’m influenced.

Having said that, of course, I’m working with particular material and a decision process happens in which I’m using it – in this piece, the material being a faceless female body, a sick, half-dead body. I wanted a way in which these CG bodies could refuse their own image – this inherent idea of perfection within these rendered digital bodies – and how there might be ways to sabotage that. I wanted to work with images that always perform work through the image itself, leaving space to create new connections and positions with our real bodies and the labour they perform. The jellyfish is part of a family of creatures that can mutate, even change the structure of their DNA. I liked this as a speculation for rethinking our own images and our own bodies. The jellyfish here becomes a prototype of how to be.

Flawless skin, hairless bodies and perfectly honed limbs… all objects of physical attraction and aesthetic beauty. And all co-opted by our hypercapitalist society in the name of commerce. As a female artist, how do you relate to these images of the virtual female body that you create? Are you further objectifying the female in order to make an over-arching feminist statement? Or is it a commodification of the female body itself?

As I already touched on, I’m uninterested in these outdated ‘readings’ of female forms of representation. I think we all realise that we live in a world where both images and the infrastructure in which we act as a political subject and how we situate itself go hand in hand. There aren’t these binary readings, I feel that as artists or political subjects we need to be agile, especially in our current climate. I’m interested in how these CGI objects of women might be able to form different and speculative ideas towards our own bodies and create new relationships to labour, particularly female forms of labour and how we might perform as workers. I feel we are in a moment where we need to re-think traditional ideas towards representation and propose structural changes. Of course, there are moments when a clear, forward-facing representation is necessary and vital, but I think fundamentally this isn’t a stable, solid, unmoveable thing. Things are changing so rapidly at the moment; coming up with new languages and ways to approach a position is important, and something I’m constantly thinking through in the work.

We haven’t really touched on the elephant in the room: the dominance of the white patriarchal hegemony. Who demands, creates and pays for these idealised representations of the female body? Besuited white guys pulling the strings at the world’s largest multinational corporations… Are the bodies you create attempting to create a new kind of “capital”?

Yeah for sure. I mean, of course, the world is dominated by white rich men but sometimes there is a level of tokenism. Of course, most marginalised people want structural change, with new ideas, new bodies that collectivise. Through my solo work, I’m concerned with experimentation and forming new relationships to representation to consider what agency our own political bodies might have within these highly coded spaces of hyper-capitalistic forms of representation. How these CG bodies in turn have a relationship with our physical bodies and how the infrastructure of these spaces need to be re-thought and remade. I feel like, for the past few years, working with this material seemed the most important way to think through these ideas.

Prior to your solo show in Berlin in 2014, you were working largely on collaborative projects as part of Auto Italia South East’s commissioning programme. Was it a difficult transition to start working alone on your own artworks? Do you collaborate with other people in the creation of your CG prints and videos?

I think there is always a misunderstanding with how work is made, and the creative labour involved in making and producing. I love collaborating and I’m currently the Director at Auto Italia along with Marianne Forrest and Edward Gillman. It’s important that there are spaces for younger artists to be supported and work through ideas, find forms of alliance in such difficult times. I mean there is a huge crisis in London at the moment within the artistic community and supporting each other is completely fundamental to creating forms of care and empathy and also just making space to particulate and be able to experience incredibly interesting and exciting work.

In my practice, I do collaborate with my partner Theo Cook, who is primarily a camera operator on feature films and also has a background in photography. We discuss the role of image making a lot and work together to produce work. I also always talk about my work to other friends and artists, and sometimes work with friends on the sound design. I’m currently developing some new collaborations with friends this year which I’m particularly excited about.

As one of 45 artists in residence at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, has this year been a time of research and experimentation for you? What has been the highlight of your time there?

I honestly think the other artists who I have met have been the most rewarding part of the residency. London is unfortunately very white and very privileged, and though there are many artists there who are exceptions to the rule, in my own experience of living and working in London, I have never met so many peers from so many different countries as here at the Rijksakademie, including Indonesia, Pakistan, Israel or Turkey amongst many others. Of course, through Auto Italia, I had worked a lot internationally before, but here you have to spend a huge amount of time with each other, forming really strong friendships; it does make you question your process, the role of art within your own cultural heritage and what politics affect you. Even if it is engineered, it feels like a breath of fresh air to be surrounded by so many different nationalities, especially as we see the rise in support towards fascism across the West.

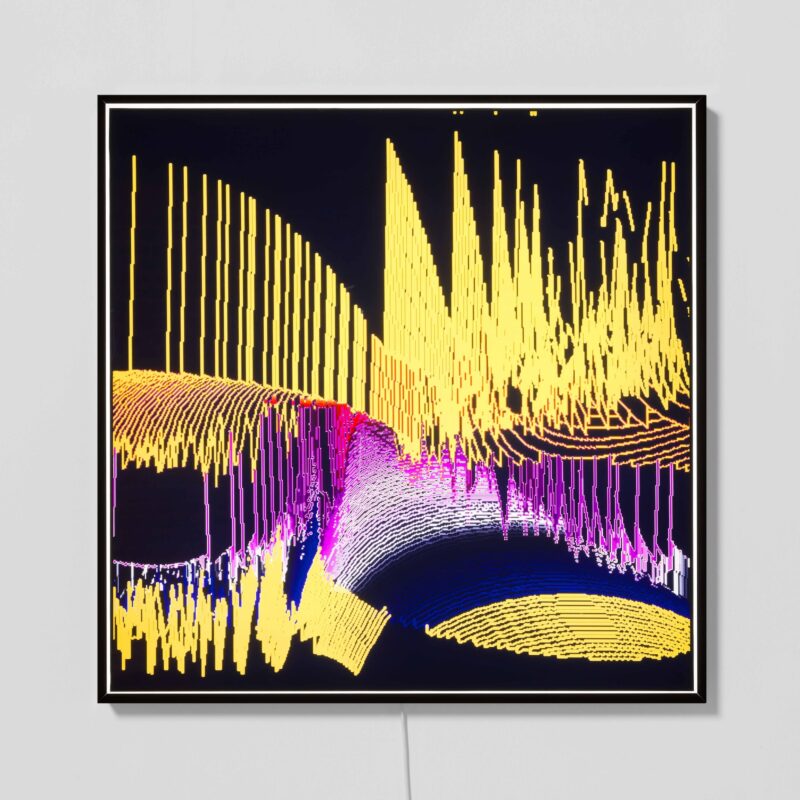

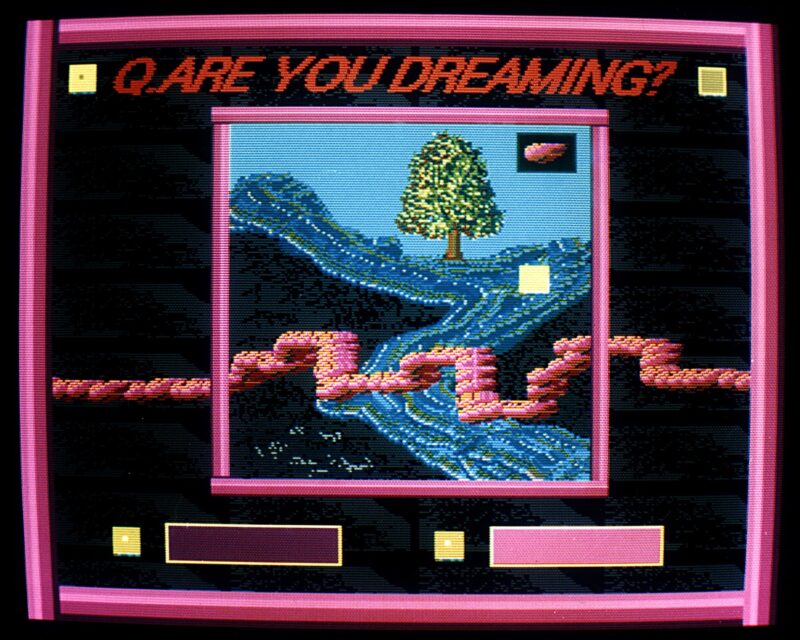

Captions

- (lead image) Kate Cooper, We Need Sanctuary, 2016. Video still. Courtesy of the artist.

- Kate Cooper, Ways to Scale, Installation View, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and VITRINE.

- Kate Cooper, Ways to Scale, Installation View, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and VITRINE.

- Kate Cooper, Rigged, 2014. Video still. Courtesy of the artist and KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin.

- Kate Cooper, Rigged, 2016.Installation view. Courtesy of the artist.

- Kate Cooper, On Coping, 2015. Digital Still. Courtesy of the artist and Auto Italia.

- Kate Cooper, Experiments in Absorption, 2016. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist.

Links

VITRINE exhibition: http://www.vitrinegallery.com/exhibitions/kate-cooper/

Auto Italia South East: http://autoitaliasoutheast.org

Rijksakademie Artist Residency: http://www.rijksakademie.nl/ENG/residency/

About the Artist

Kate Cooper (b.1984, Liverpool, UK) lives and works in London and Amsterdam. She is the Director and co-founder of the London based, artist-led organisation Auto Italia and is currently a resident at the Rijksakademie Amsterdam. Solo exhibitions include: Piece Unique, Cologne, Germany (2016); Care Work, Der Würfel, Neumeister Bar-Am, Berlin (2015); Experiments in Absorption, ABC, Berlin (2015); and Rigged, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin (2014). Group exhibitions include Commercial Break, The Public Art Fund, (2017); Insomnia, Bonniers Konsthall, Stockholm (2016); Spending Quality Time With My Quantified Self, TENT, Rotterdam (2016); The elegance of an empty room (Film Screening), Kunstverein Hamburg (2016); Public, Private, Secret , International Centre of Photography, New York (2016); Glamour, CAG, Connecticut (2016); Secret Surface, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin (with Auto Italia) (2016); The Long Progress Bar, Lighthouse, Brighton (film screening) (2016); How to live? Future images yesterday and today, Wilhelm-Hack-Museum, Mannheim (2015); Body Me: The Body in the Age of Digital Technology, Frankfurter Kunstverein (2015); Cookie Gate, Ellis King, Dublin (2015); Egress (with Colleen Asper) K,P!, New York (2015); Under the Clouds: From Paranoia to the Digital Sublime, Serralves Museum, Porto (2015); Liebe Deine Maschine, Kunstverein Hildesheim (2015); Humain Trop Humain, Palais de Tokyo, Paris (film screening) (2015); Jerwood/FVU Awards, What Will They See of Me? What will they see of me?, Jerwood Gallery London, CCA Glasgow (2014); and Total Body Conditioning (Film Screening), Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw (2014). Forthcoming projects include Art in the Age of the Internet at ICA Boston in 2018. Cooper was the recipient of the BEN Prize for Emerging Talent, B3 Biennial of the Moving Images, Frankfurt (2015) and the Schering Stiftung Art Award, Berlin (2014).