After spending three months at the British School at Rome at the end of last year, Grant Foster returns to London in top form, presenting a solo show at Tintype Gallery (on until 3rd June 2017). Entitled Ground, Figure, Sky, this exhibition features a new series of paintings that have a mocking nostalgia for the past while sending up our current popular penchant for curated beauty. Often depicting children and executed in Neo-Classical lines, these artworks can push the viewer into uneasy terrain, suggesting narratives from Grimms’ fairy tales or a creepy fixation with child portraiture, a tradition that dates back to the 18th century in the UK with the likes of Thomas Gainsborough, Sir Joshua Reynolds, George Romney or Thomas Lawrence. Spanning painting, sculpture and works on paper, Foster’s practice borrows from the traditions of British Romantic painting while touching on the absurd with one fanciful brushstroke and then flitting forward to an uncertain, sinister future.

It has only been a few months since you returned from your fellowship at the British School at Rome. Do you see a marked change in your work pre-Rome vs post-Rome? For me, the new work feels more drawing-based, the brushstroke less laboured and more spontaneous and the colour palette more vibrant. Could this be the Rome effect?

I don’t know if I’d call it the Rome effect but things did change. A group of us visited the Roman Forum in our first week, and there was a discussion that came up which stayed with me. The Forum is a vast archaeological site that is thought to be the beginning of Rome. However, it was suggested that there’s actually another civilisation underneath the Forum itself which dates back to the Etruscans. We ended up having a discussion about why the Romans wouldn’t want to excavate any further. It was suggested, speculatively, that perhaps the Vatican wouldn’t want to contradict the narrative of Roman history. Even if this is true or not, it got me wondering — maybe time runs alongside truth and we can delineate this vertically? Imagine you’re standing at the base of an archaeological site and you look up, way above you — you’re not just looking up — you’re actually looking up at the present day from where you stand in the past. Perhaps the idea of time travel could be arranged on a vertical axis. This very simple idea really struck a chord with me and became the title for the show at Tintype; Ground, Figure, Sky.

The studio itself at the British School was massively helpful and actually facilitated these new paintings. The larger paintings were made very quickly; the image itself generally executed in one go — this is the new shift. I painted them on the floor, and my body moved over the surface in a different way. It always takes me a bit of effort to hold back. My temperament is geared towards pushing an image as far as it will go. I remember painting three large paintings in a few days, mostly at night, and feeling totally manic and alive doing so.

I guess this is what you mean by spontaneity. Yes, some of the paintings do appear like that but in my mind it was more complex than that. With hindsight, I realised I’d actually made some of these images in notation form, either through text or sketch years ago. I’d bought a few old notebooks with me, and the larger paintings originated from drawings within these. That was the spontaneous moment if you like, realising that I had direct sources with me and the paintings didn’t need working out from scratch. That was liberating — here’s an old scribble from a notebook of a balding-youth-man cutting down the last remaining tree on the planet. Right, let’s make that a big painting at 2am.

The child is a central motif in this new series of painting as it has been in the past. What does the symbolic child in your work represent or stand in for? Are they naughty or nice? Instigators or angels?

Originally, I started painting children to find out if this was an okay thing to do. Was this somehow beyond the pale? But I soon came to think of the associations of the motif as more complex than the question itself — it’s almost as if children are the reason we bother to uphold our own morals and decency. You think about how adults behave when they’re around children — once the kids are sent off to bed, the booze comes out and everyone starts shouting at each other — or at least for me, that’s how it was when I was a child!! It’s as if the very presence of children forces us to behave differently as to how we act in their absence.

But then there’s this other edge to the imagery which I find terrifying. Yesterday, I was watching the news, and there’s this report about the upcoming French presidential election. The French National Front have a huge popularity with the under 25s. I found that amazing. Just visually. Imagine all these fresh-faced teenagers bouncing down the shopping mall, banging on about sovereignty and decentralisation. And then it dawns on you… what we’re witnessing over such a short space of time is a profound shift, with what I thought were accepted attitudes. I feel like that is unprecedented. I’m approaching my mid-thirties now, and I’m starting to see the fault lines develop between my generation and those who came after who don’t know life without the Internet.

I’ve actually started to think of the newer paintings as less about the idea of the child as a cipher for morality — I feel the figures now have undetermined ages. Yes, they’re youthful but they’re not children. That opens the narrative up, and the readings become less prescriptive perhaps. I feel like I’m pushing the works into something that’s akin to fable — you know the way in which fables offer fantastical things but direct you firmly back into the real world. A good friend told me about a book, The Notebook by Agata Kristof — it’s clever as the language is very stark, almost like a fairy tale and yet the most terrifyingly sickening things happen. It’s as if the fairy tale, in its stark simplicity, becomes the method for you to suspend your disbelief. I’m becoming more interested in this. I mean, how else are we supposed to process the bizarre things that are happening in the world?

As an artist whose main medium is painting, it is incredibly difficult to distance yourself from the weight of art history. Is this a burden or a benefit for you? What artists inspire your own practice if I may ask?

I wouldn’t say it was a burden. I find history liberating. It’s through history that we’re able to synthesise our present moments. And what I mean by this is that I’m not necessarily talking about binary information like dates and historical facts, but a sense of who we are, where we’ve come from and what we face – history alerts us to this and it’s often uncompromising.

Regarding who inspires me, it’s a difficult question for me to answer with any real accuracy. It’s evolved as I’ve grown older. I used to love Hockney when I was younger but now I think he’s a bore. I have always passionately hated Howard Hodgkin but now that he’s dead, I’ll probably warm to him. It changes. I think Andreas Hofer (Andy Hope 1930) is really interesting. He messes around with time by presenting superheroes who are pitted against figures of historical evil — it makes you think about the complexity of good and evil as he questions whether they’re absolute. Picabia has stuck with me for a long time — the way he continued to shift everything, to me, showed a real lack of concern for a bigger picture. That lack of concern for the bigger picture became the bigger picture if you like — and I’m into that attitude. As an artist, I think the goal is to reach a point where you can actually make whatever you want and it makes sense — like a form of perception that intuitively links seemingly disparate ideas.

Your subjects appear steeped in the past given their mode of dress – like a character from a Neo Rauch painting but without the overlying historical narrative. Could you talk about the kinds of source material you use in your practice?

I remember around 2013 the Tories were pushing this idea of the pastoral — David Cameron was photographed feeding a baby lamb, and Iain Duncan Smith was talking about getting on your bike and riding ten miles to work. There was this insane crossover between benefit sanctions and Victorian values.

Around that time, I’d come across a book of children’s illustrations from around 1920 by a publisher called Blackie and Son — it seemed to chime with the images I was seeing in the news. These illustrations are bucolic and sometimes racist. I couldn’t help connecting those images with what I was seeing in the tabloids and therefore the wider political climate. It felt and still feels like nostalgia is being used as a tool to suck us backwards. In a sense, because my paintings don’t have the same overt historical narrative of Rauch, it’s because I feel like I’m dealing with the present. They just appear to be of an unspecific past — it excites me to think of how they’ll age.

I catalogue the source materials in chronological order, inside folders which are mainly newspaper cut outs, images from the internet and these stiff little children’s illustrations. Recently I’ve been looking through the folders, and I’ve noticed there’s less and less photography and more drawing. This wasn’t really conscious. I guess the sources evolve as the painting does. In Rome, I was working directly from drawing — the aim is to synthesise both sets of information. On the one hand, the papers keep you up to date with whatever grim perversity is happening, and then the drawing refines and personalises it somehow.

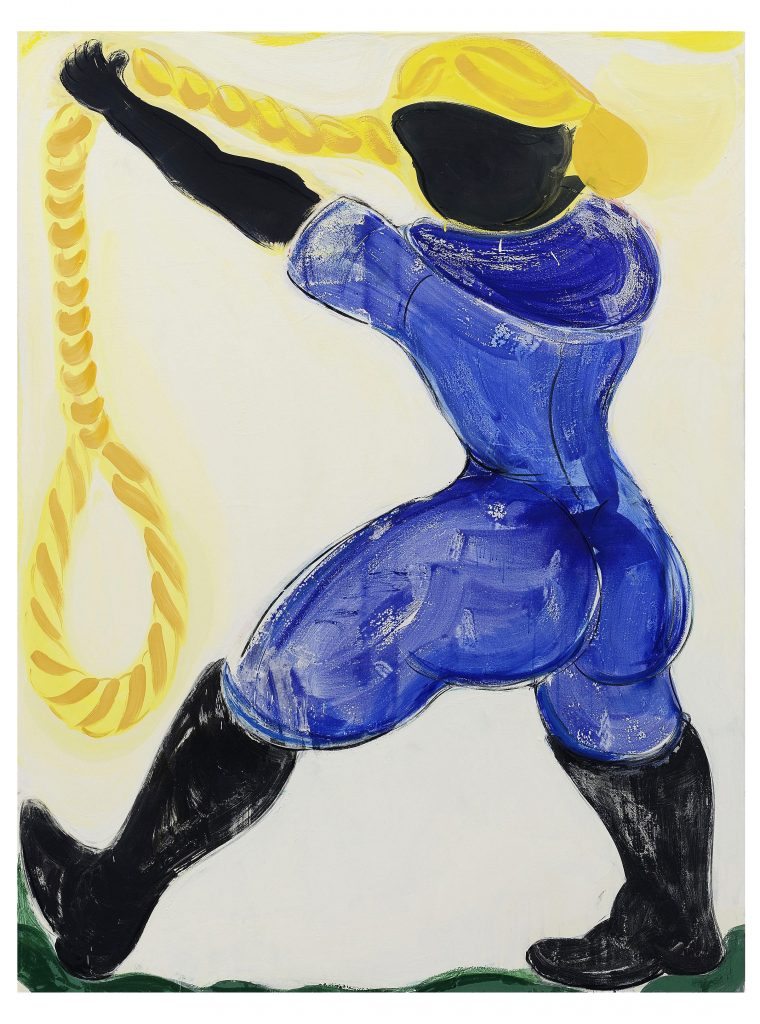

There is one painting in your current show that I would love to know more about. “Beside the Boot, the Truncheon Rests” depicts a voluptuous figure in black face, wearing tall black boots and a cobalt blue jumpsuit, with a long blonde mane braided into a noose. Pray tell…

It was originally a figure flying a kite but I felt as if that wasn’t enough. I reworked it, and the composition led to these three velvety black points in the painting — the arm, face and boots. Once the painting had settled down, I started to understand it, as if the other were taking back their power — through whatever means necessary. The painting isn’t about blackness or womanhood – perhaps those ideas are hinted at. But because the painting, like all my works, is essentially an extension of allegory, I feel like that prevents the work from being understood didactically — I’m not interested in presenting one singular meaning.

I mean, I grew up in a small English seaside town within a single mother West Indian Catholic family. In that context, we were the outsiders. But the context we’re perceived in is fragile and susceptible to change. For instance, my mother holds very old school British views and yet she’s West Indian by birth — she makes me realise that context is highly nuanced and difficult to pinpoint. I think, in many respects, meaning operates in this way.

To me, that painting summarises how I felt about Rome. During the days, I would wander around and I noticed the police wore these incredibly stylish black boots. With all people who choose a position of authority, there’s this sinister-authoritarian energy — dressed in jackboots and tight trousers. Stylish violence felt very palpable. And then you come across these huge, compositionally dynamic statues; however beautiful, they seem to border on the celebration of state sanctioned violence. In many ways, I consider that painting to almost be a monument to the nuance of revenge, violence and otherness.

You also make sculptures alongside your painting practice. How does your three-dimensional practice intersect with your two-dimensional practice? Does one inform the other? In past shows that feature both paintings and sculptures, it feels like pictorial elements from your paintings literally pop out from the canvas into the space as three-dimensional objects.

I never really have felt like I was one of those easel-kisser painters — slogging out a painting for months and months. I was behaving like that for a few years but it eventually became laborious — and I felt like I could see that in the paintings. So the sculptures developed out of this fear — if I was in the studio and didn’t feel like painting, making sculptures seemed like an obvious step.

Generally, I’ve always tried to keep them as low-fi as possible, partly because I want to be able to do the work myself but also because I’m interested in this idea of informality. I think of the sculptures like drawings, in that they’re of specific things. Therefore, there’s little deviation from the initial impetus, which is profoundly different to how I approach painting. Consequently, they seem to have a relationship of co-dependency.

I made a wax bust of Aubrey De Grey, who I’m slightly obsessed by. He’s a life scientist who believes ageing is a disease that can be treated. With this paradigm shift, he raises the prospect of future generations living well into their 500th year. He also looks like a depiction of God in one of those free handouts you get sometimes when you walk into the tube — with this huge beard and furrowed brow. I liked the idea of him promising the nearest thing to eternal life and then placing him alongside my paintings of children. It seemed kind of poignant to me at the time.

Captions

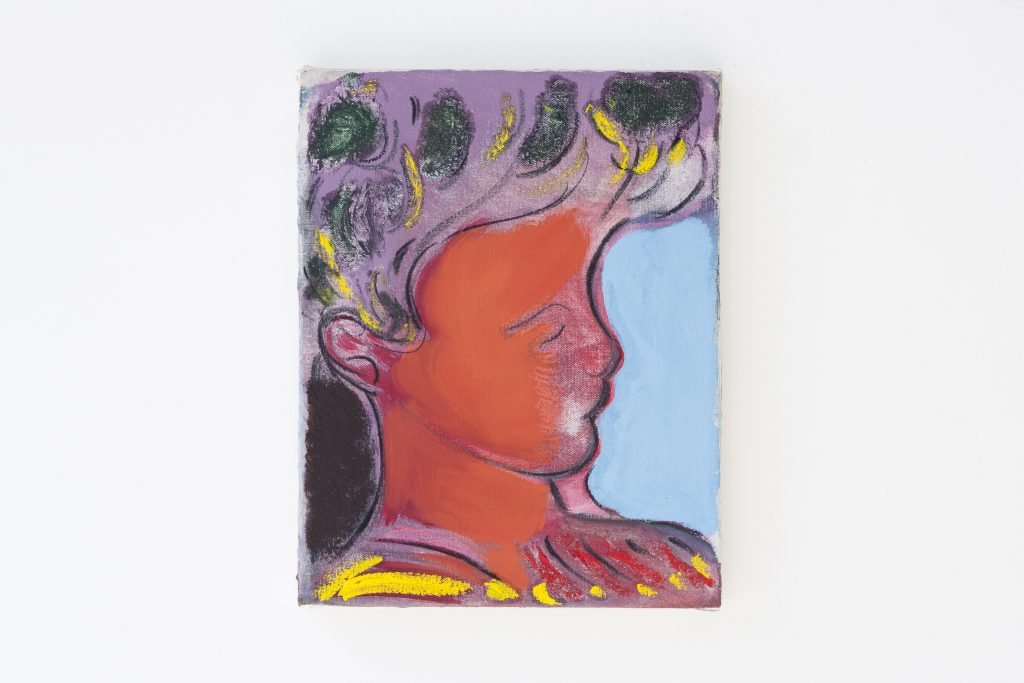

1 – Grant Foster, Vanity, 2016, charcoal, glue, pigment and oil on canvas, 36 x 28 cm.

2 – Grant Foster, Ground, Figure, Sky (exhibition view), Tintype Gallery, London, 2017.

3 – Grant Foster, The Prisoners’ Dilemma, 2016, glue and pigment on canvas, 70 x 50 cm.

4 – Grant Foster, Popular Insignia (exhibition view), Galleria Acappella, Naples, 2016.

5 – Grant Foster, Tomorrow’s Hero Today, 2016, charcoal, glue, pigment and oil stick on canvas, 180 x 135 cm.

6 – Grant Foster, Beside the Boot, the Truncheon Rests, 2016, charcoal, pigment, glue and oil on canvas, 180 x 135 cm.

7 – Grant Foster, Salad Days (exhibition view), Ana Cristea Gallery, New York, 2015.

Links

Tintype Gallery: http://www.tintypegallery.com/exhibitions/ground-figure-sky/

Artist’s website: http://www.grantfoster.org/index.html

About the Artist

Grant Foster (b. 1982, Worthing, UK) lives and works in London and graduated from the Royal College of Art in 2012. Foster’s recent solo exhibitions include Ground, Figure, Sky, Tintype Gallery, London (2017); Popular Insignia, Galleria Acappella, Naples, Italy (2016); Salad Days, Ana Cristea Gallery, New York (2015); and Holy Island, Chandelier Projects, London (2014). Recent group exhibitions include Mostra, British School at Rome, Rome (2016); The Classical, Transition Gallery, London (2016); SPORE, Kennington Residency, London (2016); Carnival Glass, Block 336, London (2015); Rx for Viewing (with Jesse Wine), Ana Cristea Gallery, New York (2014); and Bloomberg New Contemporaries, Spike Island, Bristol and ICA, London (2013). Grant Foster was a prizewinner in the 2008 John Moores Painting Prize in Liverpool, and was awarded the Rome Fellowship in Contemporary Art at The British School at Rome in 2016.