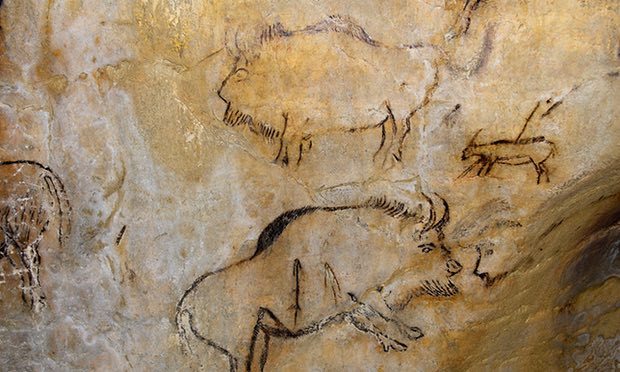

On the origins of art … paintings in the prehistoric cave of Niaux, France. Photograph: Tuul and Bruno Morandi/Getty Images

Why did human beings invent art? Why do we make it, look at it, revere it and want to possess it?

Mona (the Museum of Old and New Art) in Tasmania offers some bold and provocative answers. I heard about its latest exhibition, On the Origins of Art, from participant Mat Collishaw, whose art is nothing if not provocative and just the style to suit a museum that seems to want to be the thinking person’s Saatchi Gallery. Collishaw has created a zoetrope sculpture of fluttering hummingbirds to illustrate the theory that early human beings evolved art for the same reason hummingbirds evolved gorgeous feathers and elaborate dances: to seduce the opposite sex.

Is art simply a preening display to attract mates and carry out the biological imperatives identified by Charles Darwin? There are a couple of anecdotal reasons to find this idea plausible. One is that artists from Fra Filippo Lippi, a friar and religious artist who eloped with a nun he had seduced while painting her in 15th-century Florence, to Lucian Freud, have often been very good at finding sexual partners. And after all, so many people choose art galleries for dates.

But I can think of a problem with this idea. In speculating on why art originated it is first necessary to decide when that happened. How far back in evolution does art go? Should we regard the symmetry of handaxes made before the appearance of homo sapiens as art or even, as the British Museum’s current show South Africa: The Art of a Nation suggests, a stone resembling a face that was picked up by an Australopithecine?

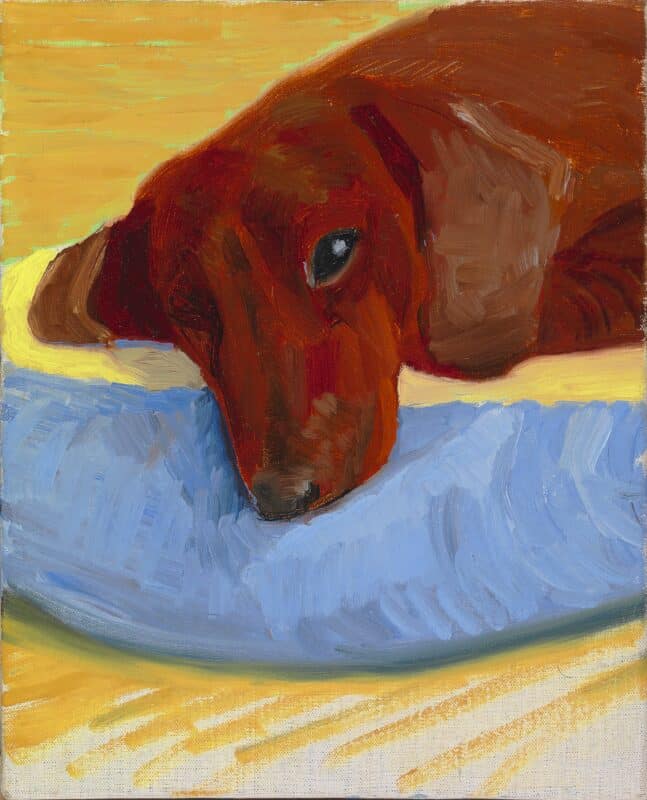

Such stirrings of art are significant. Yet for me, the first true art is cave painting. Even if we concede that handaxes have sculptural qualities, the leap forward when homo sapiens started painting and drawing animals on the walls of caves in Spain and France during the ice age is astounding, and it is difficult to see how cave art could be sexual display. The sublime charcoal portraits of bisons that I recently saw in Niaux cave in the Pyrenees are located far underground in a vast natural vault: it is hard to picture a cave artist leading a girlfriend or boyfriend this deep underground by the light of a flickering torch in order to have sex in the cold and damp. “Come and see my etchings. They’re a mile underground.”

On the contrary. The deliberate mystery and estranging subterranean location of cave paintings suggests that the origins of art have much more to do with religion than sex.

The sexual display theory is advanced in the Mona exhibition by one of its four curators, the psychologist Geoffrey Miller. The other scientist-curators suggest similarly audacious explanations for the existence of art. Steven Pinker, author of books such as The Blank Slate, shares a hard-headed Darwinian perspective. He suggests that art evolved as a byproduct of other human skills and needs, including conspicuous consumption, and that aesthetic pleasure originates in our practical appreciation of “cues to understandable, safe, productive, nutritious or fertile things in the world”. Brian Boyd, like Miller, thinks art has grown out of the signalling systems that all animals use in mating and the avoidance of danger, while Mark Changizi suggests it reflects our capacity to mimic nature.

It’s fascinating stuff, but such theorising needs to be set against a firm history of how and when art actually did evolve. This story is becoming ever clearer. Some of its milestones can be seen, far from Tasmania, in the British Museum’s South Africa show. It is dangerous to confuse decorative instincts, or even the sense of beauty, which handaxes suggest evolved very early in the human story, with the higher, more complex activity that is art as we know it. The art in ice age caves such as those in Niaux has the same qualities as the art of Rembrandt, Da Vinci and Picasso, and is as hard to reduce to a simple biological urge or obvious evolutionary need. At its point of origin in dark caves deep in the Earth, art is enigmatic, poetic, profound and dreamlike. It is born sublime. You can’t explain it until you can also explain Mark Rothko’s Seagram murals.

Darwin had Raphael prints in his bedroom, but I doubt if he thought they were as susceptible to logic as the honeycombs in his beehives.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.