Art is magical. It is a fairytale. It can make you rich. It can make you poor. It can turn everything you thought you knew inside out and upside down.

It has made Damien Hirst rich, colossally so, and now it has done something else. It has redeemed him. For years he has appeared a figure of strangely wasted and ruined promise, whose commercialism snuffed out his artistic spark. Yet with his exhibition Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable, which fills not only a Venetian palace but also the capacious halls of the ship-shaped Punta della Dogana at the mouth of the Grand Canal, the arrogant, exciting, hilarious, mind-boggling imagination that made him such a thrilling artist in the 1990s is audaciously and beautifully reborn.

The young artist who put a tiger shark in a glass tank never died, after all, and we who lost faith in him look like fools for failing to believe.

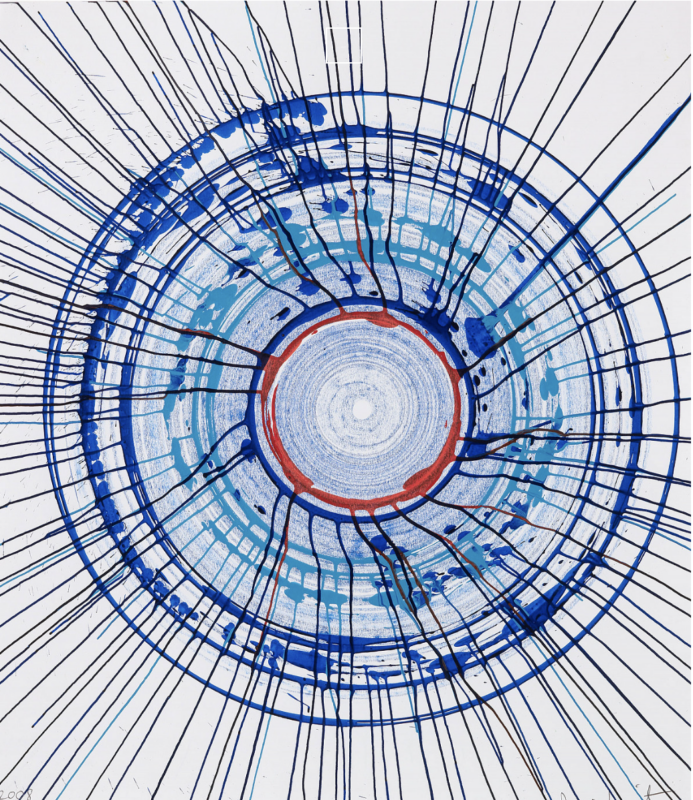

Not that he is taking credit for the Egyptian statues, Greek armour, Chinese bells, unicorns, medusas and other wonders that unfold in ever more mind-boggling richness and strangeness as you explore what amounts to an entire museum of ancient history and myth. Hirst claims a new role, that of archaeological impresario, presenting to the world one of the most important discoveries of recent times. In 2008 the wreck of a treasure ship called the Apistos (meaning “the Unbelievable”) was found on the seabed off east Africa. It sank about 2,000 years ago. Its unique cargo of global artefacts, assembled by a freed slave called Cif Amotan II, have spent two millennia undergoing a “sea change” straight out of Shakespeare’s Tempest, becoming wrapped in coloured corals and bizarre crustacean growths – until the archaeologists who found this sunken marvel asked Hirst to use his millions to help recover it.

If you believe that, you’ll believe anything. The curators who told this bit of hokum straightfaced at the start of the press view deserve bonuses, if Hirst has not yet bankrupted himself creating this luxury masterpiece. Telltale clues that we are not really seeing ancient works of art include a barnacle-encrusted statue of Goofy, a sculpture of Mowgli and Baloo, and what looks like a Jeff Koons statue that has been left on the seabed for a few years. The multicoloured corals are mostly painted bronze.

I was disappointed for a moment. Photographs and films of the salvage project Hirst’s team carried out in the Indian Ocean make you hope for an underwater exhibition or a boat ride through a sunken world. Instead, the display at Punta della Dogana starts with a gargantuan fake Aztec sun stone that frankly looks like a prop from an Indiana Jones film. Is this going to be any more artistically rewarding than a trip to the Harry Potter studios to see the sorting hat? But Hirst’s wizardry proves to be the real thing.

It takes a kind of genius to push kitsch to the point where it becomes sublime. Hirst’s hero Koons has done something like it with his giant reflective balloon dogs. Here, the kitsch doesn’t so much grow on you as wrap you in its tentacles and drag you down into its underwater palace. After one implausible fake of an unknown pharaoh’s portrait, I was disgusted. After a roomful, followed by rooms full of everything from Roman dinnerware (purportedly) to a massive coral-covered statue of a multi-armed woman fighting a writhing many-headed Hydra, I was intoxicated.

The exhibit that completely overcame the last shreds of scepticism was a display of two enormous skulls of Polyphemus, the one-eyed cyclops that tries to eat the heroes of Homer’s Odyssey. These are marble models of mammoth skulls: archaeologists believe, says a display label, that the hole for the mammoth’s tusks may have inspired the myth of a race of one-eyed giants.

The thing is, this theory really does exist, and you can read a similar label beside a fossil skull of a prehistoric elephant in the Natural History Museum. Throughout this exhibition, real historical information is offered about what are clearly fakes. Then again, some of the fakes are more plausible than others. Are those real Roman coins? Is that a real Roman spoon? I can’t tell.

It is the combination of intricate detail and stonking, mind-blowing scale and quantity that makes this collection so beguiling. By the time you get to a room full of gold objects, including a majestic-looking cornucopia (horn of plenty) and a gold replica of one of the sculpted portraits of life in west Africa, you feel drugged with history and art.

It is not just a random mass of stuff, but a subtle meditation on the practice of collecting, on museums and why we go to them. Throughout the exhibition, sculptures in rollicking bad taste alternate with glass cases that evolve Hirst’s oldest, most quintessential idea – putting things in vitrines and cabinets – into a profound image of the act of collecting. These cabinets contain things of apparent antiquity and historical meaning, arranged – as they might be in a very beautiful museum – by a fastidious curator. What are the principles of arrangement? How have the treasures of the Unbelievable been classified? How do we classify and know anything at all, and what drives people to do it?

This fictional museum is not only impressive, but moving. Hirst shares his passion with us. He obviously loves art, loves the dark and inexplicable mystery of it. He communicates, too, a love of history – or perhaps, rather, a love of time. Art is changed by time as wrecks are changed by the sea. Today’s spoon is tomorrow’s wondrous relic.

Will Hirst one day be in the history books as a genius? It looks a hell of a lot more likely after this titanic return to form.

At Palazzo Grassi, you enter the second part of the exhibition to see a foot … a leg … It is the biggest statue I have ever beheld. Hirst has created a figure on the scale of ancient monuments like the Colossus of Constantine, whose marble foot survives in Rome’s Capitoline Museum. Even more disorientating, this figure that dwarfs and awes a now seriously befuddled crowd of journalists has been fitted into a tall, narrow galleried courtyard. It is a monstrous bronze man out of a dream or gothic novel. Some say it represents Pazuzu, and that the bowl it holds is for human blood – but the curator disagrees.

When did I last see a contemporary artwork that surprised, unsettled and delighted me as much as this? It was probably when I walked into the Saatchi gallery in 1992 and saw a tiger shark apparently swimming towards me, mouth open.

Hirst has once again found the underwater grotto in his mind where the monsters live.

Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable: Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana, Venice, from 9th April until 3rd December

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.