Room after room, turn after turn, Wolfgang Tillmans’ Tate Modern exhibition teems with images large and small. Images alone and arrays of larger and smaller photographs, framed and unframed and attached to the wall with bulldog clips, hung high over doorways and shuffled on a table.

A young man’s neck, a knee, a hand stuffed down a pair of shorts. A glimpse of flesh as someone turns. A boy looking at his phone at a London roundabout, a young man in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, all in fuchsia next to his shiny purple car, mobile phone in his hand. A pair of balls and anus, close-up, huge on the wall. A city seen from the sky from an aeroplane window; another city, veiled in pollution. You can get very close or not nearly close enough. Or even too close.

These shifts in distance and proximity, scale and presentation let Tillmans’ photographs, in all their variety, breathe. Such stratagems are familiar from earlier exhibitions of the German artist’s work, but are more than just a way of amassing his material. They take account of our mobility and insatiable hunger for the next thing, in order to slow us down and pay attention.

There is music. There is dancing. Bewilderment is part of the pleasure, as we move between images and photographic abstractions. Tillmans’ asks us to make connections of all kinds – formal, thematic, spatial, political. He asks what the limits of photography are. There are questions here about time, place, belonging, voyeurism, affection, sex. After a while it all starts to tumble through me.

Here is a laser print of a faded fax, itself a print of a photograph of a young man crouching, in a position like praying. Through all its technical reproduction, the image assumes a new quality, both degraded and as delicate as a pen and wash drawing, the faded memory of something seen or encountered, bought back to mind.

Then we are swept away on a drive down Sunset Boulevard, rear lights flaring in the night, then trudging down the grey-carpeted slope of an airport corridor, heading towards Immigration, beyond the sign that reads “Rest of World”. OK. Where next? To the studio, with its messy desk, a still life of monitors, laptops and cables, beer bottles, cigarette packs and ashtrays. Some images give you only blankness, pure colour pocked and marked by a dirty printer, a corrupted purity.

When Tillmans won the Turner prize in 2000, he used some of his winnings to buy an expensive colour printer. In 2011, he dismantled the by now defunct machine, screw by screw. A thing of silvery panels and grey shadows, the parts clutter his studio floor, surrounding the printer’s disembowelled carcass. What that thing has seen, how much use and abuse it has suffered. Then he took its photograph, as if he were looking for some secret there, some image lost inside. A little later we come to a gutted lobster shell, a fly working at a scrap of uneaten flesh in the upturned carapace on the table.

Tillmans’ work is all a kind of evidence – a sifting through material to find meaning. Now the camera is staring into a big cardboard box, half-filled with pharmacist’s tubs and packages, 17 years’ supply of antiretroviral and other medications to treat HIV/Aids. I imagine the sound that box would make if you shook it, what that sound might say about a human life, its vulnerability and value.

A whole world is here. A filthy drainpipe in Buenos Aires, a Delhi morning, Shanghai nights, Port-au-Prince and Lima seen from the air. Anders, half naked, bent over and pulling a splinter from his foot, a timeless moment of attentive self-care. Everything collides in this warren of 14 spaces. Tillmans’ 2017 is not a retrospective so much as a realignment of images and preoccupations. Reconfiguring his work, introducing pauses and interruptions, is a way of telling the story new each time.

Making a show is as much a part of Tillmans’ work as taking pictures, making a video or an installation. Or, one might add, creating exhibition spaces in London then Berlin, championing other artists, and making the best case for remaining in Europe, as Tillmans did in a series of posters he created, and which could be downloaded and distributed for free, last year.

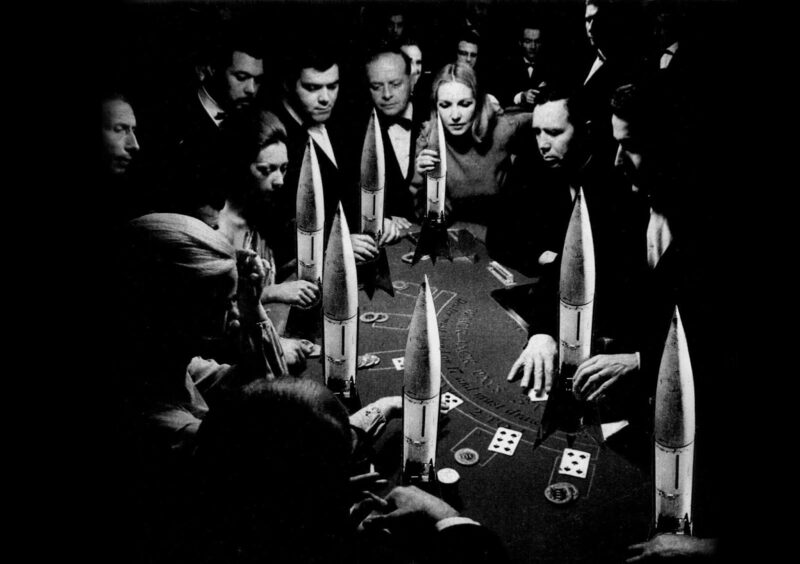

An arrangement of home-made tables fills one room. Begun in 2005 his truth study center is an ongoing project that collates all kinds of visual and written material as a kind of tabletop scrapbook of archived articles and images. It functions as a litmus test of the present moment. There are studies in brain research, and how hard it is to change people’s political opinions; global warming evidence and why it riled doubters; the cognitive process, and why it is that that people don’t care that Donald Trump lies. Here’s a pamphlet on anal play for men and women. There is too much to take in, in these background rumbles of the personal, the public and the private.

Later, music leaks into the gallery, and we are led into a blue room with acoustic baffles mounted on the walls and ceiling. A serious sound system blasts the music of 1980s British band Colourbox into the space. This is a kind of release. Colourbox was a studio band that never performed live, and the speakers reproduce their music as close to the quality of the original master recording as possible. Tillmans’ Playback Room was first set up in Three Bridges, the studio/gallery space he set up in Bethnal Green, then again when he moved to Berlin. The room is cluttered with rows of old GDR school chairs. Ignoring them, I danced alone by the window, looking out at the grey river light on a winter day.

In another room, wearing only his underpants, Tillmans dances too, to the beat of his bare feet as he moves left and right before a mark on a wall, in the video Instrument. Maybe the black mark is a glory hole. On an adjacent screen we see his shadow cast on a different wall, making the same moves, slipping in and out of synch with his other self. Dancing for himself, dissolving in the rhythm, he is both instrument and player, catching up with himself, lagging behind. This second room, we learn, is in Tehran. What a strange and compelling work this is.

Among a number of portraits – including artist Richard Hamilton, singer Frank Ocean and ex-British Museum director Neil McGregor – we find Tillmans’ own reflection, fractured in a scarred, dented and distorting metal mirror in Reading jail (taken for his participation in the Artangel project there last year).

And here is artist Gustav Metzger, who first arrived in Britain as a refugee on the Kindertransport, almost a lifetime ago. The colourful wreckage of boats beached on Lampedusa marks a more recent transit of fleeing refugees. In a further image the spotlight of an Italian coastguard helicopter is cast on a dark sea in a rescue mission off the coast.

Someone stands beneath the Gaza wall, as if they were waiting for something. White paint is hurled over the screen of a Spanish ATM in a gesture of rage and obliteration. We are coming to the end. The last room in the show is dominated by an empty ocean, heaving with contrary currents and undertows. The image is called The State We’re In. In a corner hang four modest pictures of a small apple tree, growing outside Tillmans’ old London studio, the fruit ripening. Around, the world roars on.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.