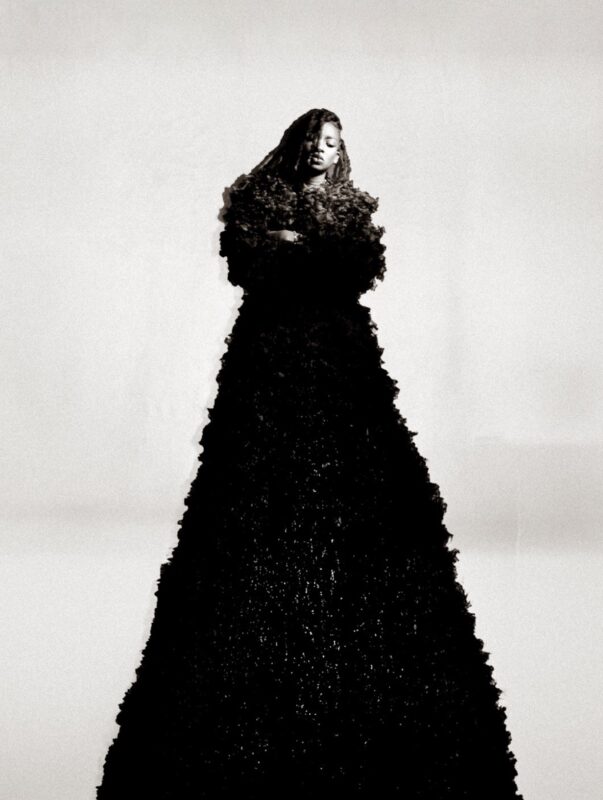

A rendering of Floria Sigismondi’s project Pneuma. Photograph: Sue Holland

You may know Director X’s music videos: they tend to win awards, attract hundreds of millions of viewers, and celebrate dancing, whether in a restaurant (Rihanna and Drake’s Work), in a high school (Iggy Azalea’s Fancy), on the marquee of the Compton Fashion Center (Kendrick Lamar’s King Kunta), or on a construction site (Fifth Harmony’s Work from Home). He’d like to inform you, however, that his newest work – a piece of installation art that projects, on to a 45ft sphere, computer graphics depicting the eventual burnout of our sun – is, as he puts it, “much more representative of the artist I am”.

Created for Toronto’s Nuit Blanche event, Death of the Sun makes the man born Julien Lutz the latest prominent music-world figure to venture into the realm of visual art. These aren’t just ageing rockers who turn to painting when their touring slows down, but stars in their prime, for whom art scratches an itch that bling can’t reach.

Jay Z has worked with the performance artist Marina Abramovic, and Kanye West has paid homage to Vincent Desiderio’s painting Sleep. Rihanna’s press conference for her latest album, Anti, was billed as a “private viewing” of the booklet artwork by Roy Nachum. Drake posted pictures of himself inside James Turrell’s lightboxes before shooting a video for Hotline Bling – helmed by Director X – that filtered Lutz’s own preoccupations with the spatial geometry of dancing through a Turrell-esque realm of saturated color.

“Boundaries are opening up,” says Floria Sigismondi, known for her surreal videos for the likes of Rihanna, David Bowie and Marilyn Manson. Sigismondi is premiering her own work, Pneuma, in tandem with Death of the Sun, at Nuit Blanche. “As a whole,” she says, “society is much more open to having people cross over into different disciplines, where before, the art world was very closed off.”

But why should it be so attractive? Lutz cites the producer Swizz Beatz, who started collecting art as a teenager in the late 1990s and now sits on the board of the Brooklyn Museum. “He brought that to [hip-hop] culture, with Jay Z: ‘Look at this art I bought.’ And Jay Z said, ‘Yeah, that resonates with me.’ And then people started going down that line and embracing that part of ourselves, where perhaps earlier [we had] a little bravado, or it wasn’t cool enough.”

Now, art itself generates bravado: where Jay Z used to boast about selling millions of albums, he now brags about being “surrounded by Warhols”, with a “yellow Basquiat” in his kitchen corner. It’s not enough to be at the summit of the rap game; he calls himself “the modern day Pablo” – just as Kanye West has insisted: “I am Pablo.”

Picasso, who clearly contains multitudes, represents what Sigismondi calls “a sense of fearlessness that our souls just crave; we’re drawn to people that can live like that”. The artists who “stick out are always pushing buttons, doing things that others have never done, whether it’s Picasso with cubism or Van Gogh with his colors.”

Not that Van Gogh was able to flog more than a very small part of his oeuvre during his lifetime – he was hardly the Jay Z of his day. But perhaps because of this, his art represents what both Lutz and Sigismondi refer to as the ideal of “purity”. Despite the corporate sponsors that might pop up at Art Basel (as they would at a Beyoncé concert), the artist, for Sigismondi, is seen to “really own” his or her work. “Artists have always been held up a little bit maybe because they can comment on the world [without] thinking about commerce. There isn’t a record company, or [someone asking], ‘What’s your audience?’”

For Lutz, working with Nuit Blanche has been “a very different experience. There’s no client. It’s me and the city doing this, and the city’s very much, ‘We’ll facilitate what you want to do.’ It wasn’t any of those ideas, like, ‘Oh, naked girls!’ ‘Oh, we can’t show nakedness.’ The piece is unique. It’s definitely my voice.”

Compacting the next 12bn years of our resident star into 12 minutes, Death of the Sun finds the 40-year-old Lutz reflecting on mortality: the star morphs from its current yellow sun stage (in its “sexy prime time”) into a bloated red giant (“what I’m entering as I gain weight, no matter what I do”, he laughs) and then collapses into a white dwarf. It also gives vent to what he calls his science fiction “nerd” tendencies.

Sigismondi sees Pneuma as a personal project too: “I had been in the past more preoccupied with the body, so it was a natural progression to go to the spirit.” It’s a short, mystical film, set to a Boards of Canada track, with flowing visuals projected on to a 33ft-high water screen created by a fountain – via a fire truck hidden away – in the middle of an artificial pond. Sigismondi herself appears as a figure in a red dress inscribed with ancient symbols and lyrics by David Bowie, himself a painter and art collector, to whom she’s paying tribute.

If anything, though, both pieces offer the antithesis of “I am a great artist” braggadocio. They’re both part of an exhibition called Oblivion, and at the end of Pneuma, Sigismondi’s figure disappears into the water as if dissipating. Death of the Sun’s scale, according to Lutz, aims to impress the viewer with a sense of our collective insignificance: “Everything is just a dot.”

- Nuit Blanche runs from sunset on 1 October to sunrise on 2 October in Toronto. Death of the Sun and Pneuma will have an extended run from 2 October through 10 October, from 7pm until midnight.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.