The first day of the battle of the Somme (1st July 1916) was the costliest in British military history. To mark its centenary, writer and photographer, Jolyon Fenwick has created a series of photographic panoramas taken at the exact position (and time of year and day) from which 14 battalions attacked in the first wave at 7.30am BST (ZERO HOUR) that fateful morning.

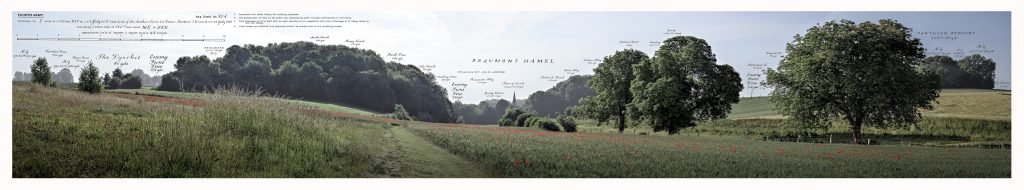

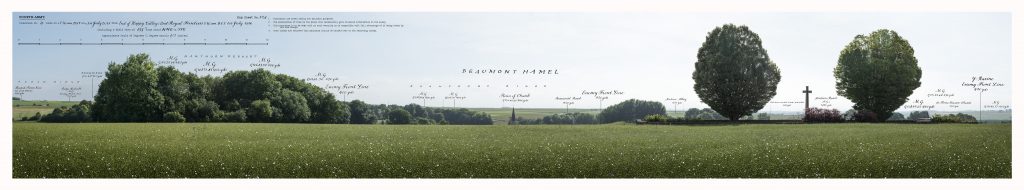

Annotated by hand in the manner of the battle field panoramas of the time with the points of tactical significance as they existed immediately before the battle, they powerfully juxtapose the hellish reality of the nation’s bloodiest battle with the pastoral peace of these ‘forever English’ fields today.

PANORAMA NO.3: BEAUMONT HAMEL Pigmented ink print on mould made, 100% cotton Somerset paper. Annotated by hand in black Indian ink. Sizes: 72” x 12” live image (50 editions) 48” x 8” live image (50 editions)

FAD managed to catch up with Jolyon and ask him some questions ahead of the opening of his exhibition.

1 WW1 marked such a change in the way that battles were fought, with its scale, ferocity, duration and the huge number of casualties. Do you think that this is what continues to draw artists to the subject?

Well yes but it’s not I think the scale of the loss and suffering alone I think that makes the First War stick in our bones. It is that its narrative contains so many of the ironies that make tragic stories stick.

After all, the war began at the end of the most glorious summer in living memory, with vast, cheering crowds waving flags at the declaration of war; everyone famously thought it would be over by Christmas. Schoolboy soldiers fibbed about their age so they wouldn’t miss it, then ended up shooting their feet off to come home. It was a time when generals still wore jodhpurs and regiments rode off to war even though the swashbuckling days of the cavalry were over. The British social classes – divided in peacetime like different species – were made to share the same ditches in the ground. The Western Front appeared like another world yet it was only a short boat ride across the Channel – officers could eat breakfast in their dugout and dinner in their club and London theatre–goers could hear the sound of the guns. Great European empires at the height of their power and confidence were brought to their knees. The British were of course at war with the cousin of their King. Both sides were fellow Christians, each sure that Christ would side with them. Late Victorian Britain had endowed a generation with a culture of grace and tenderness – the First War then blew them all to bits.

Artists, like everyone else, I think are drawn to 1914-1918 war as there appears to be an almost deliberate artfulness to its story.

2. In basing work around a past conflict are you adopting a purely historical tone, or do the themes in your work apply to contemporary conflicts?

Well I guess the panoramas are all about time. The fact of time passing must be the most sublime element of human experience. Is their anything more affecting for any of us than say going back somewhere we haven’t been for a long time and imagining the times once spent there now past and gone? In a historical sense (in other words somewhere beyond my own personal experience) I have felt this no more powerfully anywhere than on the fields of the Somme. A place where once raged the greatest battle since the beginnings of civilisation and that witnessed the greatest loss and suffering our country has ever known is now a deserted, pastoral landscape of mature deciduous trees and rolling farmland. Using the device of overlaying the annotations, I wanted the panoramas to at once show two almost unimaginable perspectives – our own looking back to what once there was (barbed wire, machine guns, noise such that a man shouting into the ear of the man next to him could not be heard, mutilation and death) and that of the soldiers at the time (if they could) looking forward to what there is now (barbed wire fencing in only cows, wooden seats for tourists next to the great mine craters and the crosses, memorials and immaculately kept cemeteries that still mark their sacrifice).

So yes very ‘historical’ in theme yet of course the panoramas’ very raison d’etre is as a memorial to our most defining day of personal sacrifice – a sacrifice that, as a measure of the price of good, will clearly apply for all time.

PANORAMA NO.4: HAWTHORN RIDGE Pigmented ink print on mould made, 100% cotton Somerset paper. Annotated by hand in black Indian ink. Sizes: 72” x 12” live image (50 editions) 48” x 8” live image (50 editions)

3. It’s interesting that you talk about how these panoramas were never seen by the soldiers commanded within the landscapes they show. As it’s obviously impossibly to control information in the same way now, what are your thoughts on the way the staff officers controlled the information their men had access to?

Well first it’s important to say that, like today, information was controlled for reasons of security which is entirely understandable. Yet the fact that ordinary British soldiers were deliberately deceived as to what faced them is undeniable – most notably on the Somme – ‘there’ll be nothing of the German defences left but the caretaker and his dog’, ‘you’ll need nothing more than a walking stick’ etc etc… Those officers in the middle who were directly responsible for their men and party to the information (battalion commanders and so on) frequently found themselves in an appalling situation. Colonel Edwin Sandys for instance in the days before the Somme attack famously drew his superiors attention to the fact that the bombardment had utterly failed to subdue the German defences. He was met with a conspiracy of denial. 80% of his battalion (2nd Middlesex) were subsequently killed or wounded on 1 July. Two months later, while recovering from his own wounds sustained on that day, Sandys checked into a London hotel and shot himself through the mouth with his revolver.

It must be said however that the Somme battle had to be fought to keep the French (who were being ‘bled white’ at Verdun) in the war however disquieting the pre-attack intelligence. It was very largely the fates rather than British generals that conspired to condemn the volunteer British soldiers that day.

4. Fabio Gygi wrote that ‘to peer over the trenches was extremely dangerous; the act of seeing became closely associated with death’ and I wondered how you felt about the juxtaposition between the sleepy, bucolic nature of the contemporary landscape and the sudden danger that once defined it?

They are such excellent questions these that I fear I have perhaps covered this above.

5. We teach the poetry of the war poets to school children in part as an act of remembrance yet aside from public sculpture, the visual arts don’t seem to occupy the same role.Do you have any feelings on whether / how the visual arts can help to ensure the horrors of this and other wars are not forgotten?

It’s a very good point. The First War did of course inspire some very affecting paintings by the likes of Nash, Sargent and Orpen yet it’s certainly true that it’s the poetry that still occupies our consciousness and steers our memory. Other than their undoubted power as pieces of verse, this is perhaps because the work of Owen, Sassoon and Blunden etc was the first in any medium to explicitly elucidate (personal accounts and diaries almost never did) the nature of the horror – ‘If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs, Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud’ etc.

It’s difficult for visual media (other than actual reportage footage which even today would in any case be censored) to compete with this – at least in actually imparting what the experience of war and its suffering is actually like. Even Guernica – for all its frightfulness – doesn’t tell us what it’s actually like being underneath 5,000 incendiary bombs. And in our age of well–advertised personal misery, I think it’s enormously important that we do understand these things and bow our heads to those who have had and still have to endure them. I often think (perhaps rather uncharitably) when I open a newspaper or supplement and read (or don’t read) of the personal trials of some celebrity: ‘well thank your lucky stars you’re not lying in the bottom of a trench with your guts hanging out screaming for your mother’. Such is the importance of our knowing our history.

Jolyon Fenwick ‘The Zero Hour Panorama 1st-15th July 2016 at Sladmore Contemporary, 32 Bruton Place, Mayfair, London W1J 6NW www.sladmorecontemporary.com

PANORAMA NO.10: OVILLERS Pigmented ink print on mould made, 100% cotton Somerset paper. Annotated by hand in black Indian ink. Sizes: 72” x 12” live image (50 editions) 48” x 8” live image (50 editions)