Tracey Emin’s new husband may not talk much or do the ironing, but when it comes to fidelity, he’s a rock. Really, he’s a rock. No, you don’t understand. Her husband actually is a large lump of rock.

As her latest exhibition I Cried Because I Love You opens in Hong Kong, the woman whose life is her art has revealed that last summer she married a venerable stone that stands in her garden in France. “Somewhere on a hill facing the sea, there is a very beautiful ancient stone, and it’s not going anywhere,” she has said. “It will be there, waiting for me.” In another interview she has called it “‘an anchor, something I can identify with”. She wore her father’s funeral shroud as a wedding dress. As Lou Reed says: “And no kinds of love / are better than others.”

The ancient Roman poet Ovid says much the same thing at greater length in his Metamorphoses, the great poetic telling of myths in which a fleeing lover turns into a laurel tree, a young man adores his own reflection, and a woman called Echo who pines for him vanishes, leaving only her voice resonating in the olive groves. Love is strange, and Emin’s marriage is an exploration of its spiritual dimension.

She told the Art Newspaper she has been reading the letters of Pope John Paul II. The late Polish pope’s letters to the philosopher Anna-Teresa Tymieniecka were revealed by the BBC in February to show an intense, long-term, apparently celibate relationship between one of the most revered modern popes and a fellow intellectual. In other words Emin has been thinking about relationships that transcend the carnal – about love that goes beyond lust.

Pope John Paul II’s spiritual love affair was in a religious tradition that goes back to the Renaissance. It resembles the passionate friendship between the Catholic genius Michelangelo and the poet Vittoria Colonna in 16th-century Rome. Both were devout, and Michelangelo was gay, but they exchanged long and absorbing letters in their old age that see love as a spiritual journey.

Michelangelo and Tracey Emin share a spiritual understanding of love, it seems. Many artists (Picasso leaps to mind) are ecstatically carnal. Others are fascinated by invisible dimensions of experience that go beyond the body. Michelangelo sculpted the human body more powerfully than any other artist, yet earthly gratification was never his theme. His heroic, struggling, superhuman nudes are physical expressions of the soul itself.

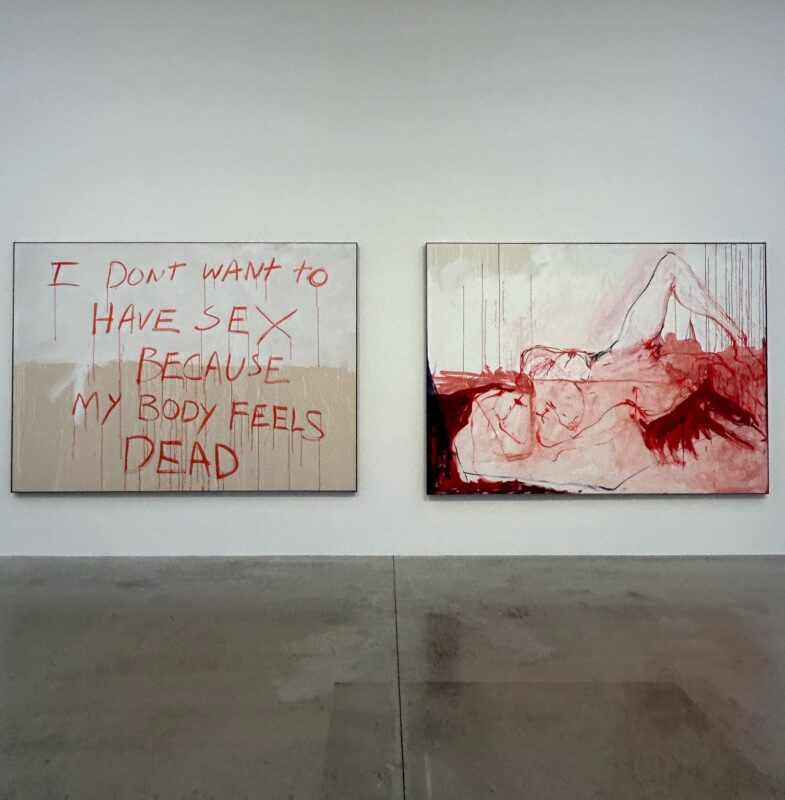

Tracey Emin too is an artist of the inner life, not the outer body. This may seem surprising since her art is so pungently located in a material world of unmade beds and, more recently, drawings and paintings of her own naked body. But consider her early work Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995. Its title sounds like a sexual boast but the 102 people she listed, including her gran, were not all sexual partners – and the form of the work, a small tent, speaks not of sensuality but intimacy. It is a record of emotional connections, not sexual conquests. Her bed, too, is an emotional image, a monument to spiritual pain and solitude; a kind of martyr’s relic. In her more recent art, in a time of her life she describes as celibate, Emin is still more preoccupied with the soul, the invisible self – and the kind of love that lets the spirit soar.

Michelangelo never actually married a rock, but he did have a vivid relationship with his favourite sculptural material: stone. In one of his letters he claims that stones themselves cry out at political oppression. In his great unfinished sculptures of slaves, human forms struggle to emerge from raw stone like souls trying to be born from the chrysalis of carnality into the life of the spirit.

Michelangelo had some funny ideas and so does Tracey Emin. That is because they are truly poetic artists.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.