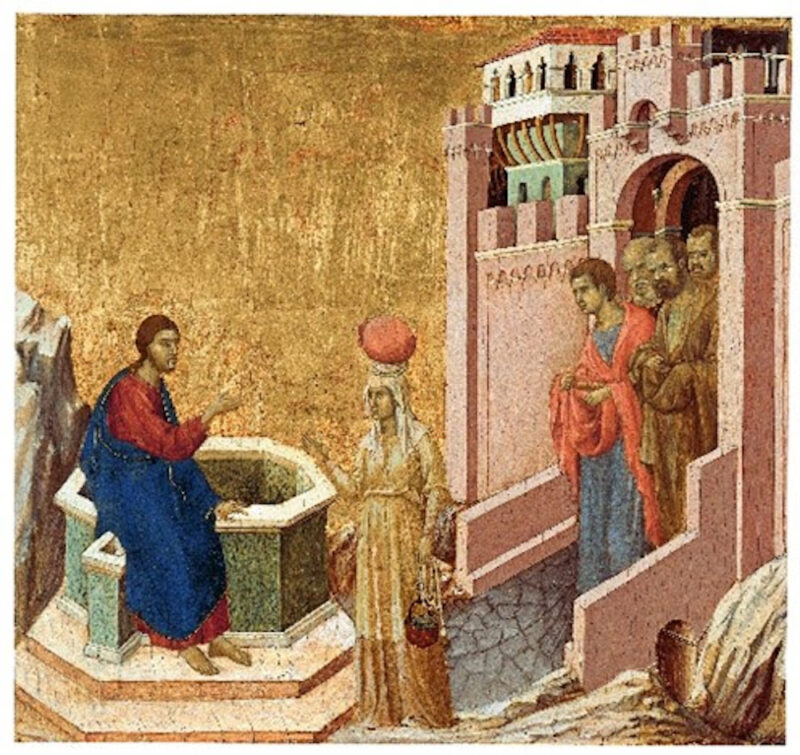

National Gallery visitors gather to gaze at the Francisco Goya painting The Family of the Infante Don Luis de Borbon (1783-4). Photograph: Justin Tallis/AFP/Getty Images

The moment the doors close for the last time on the National Gallery’s celebrated Goya exhibition will be especially poignant for the show’s guest curator.

Xavier Bray is planning a private farewell for a collection of portraits he spent more than 10 years bringing together, before they are scattered and returned to their owners.

“I’m hoping I’ll get permission from the director to have a few hours on my own when the show closes,” he says of Goya: the Portraits, which ends at 6pm on Sunday. “It’s going to be quite important to say goodbye.”

Bray may even share a few private words with the painter’s spirit. “I’ll probably have a quick conversation with Goya up there and we’ll hopefully shake hands and thank each other, and walk off, and that will be it.”

But that won’t quite be it. A feature-length film about the show, Goya: Visions of Flesh and Blood, does at least provide a permanent record of the most comprehensive collection of Goya portraits ever brought together. The film opens in cinemas around the world in February, and prominently features Bray, who is now chief curator at the Dulwich Picture Gallery.

“It gives the show a life after the exhibition, so that is some consolation,” he says.

The exhibition has been lauded as “the show of the decade”, vindicating Bray, who had to convince sceptics at the National Gallery worried that Goya’s famously black paintings would fail to pull in the crowds.

“There was quite a bit of hesitation about a show about Goya’s portraits,” Bray recalls. “They only predicted a maximum of 80,000 [tickets sold] but we’re already well above the 150,000 mark and I’m predicting that in the last few days it will be absolutely chocker with up to 20,000 more as people realise they have a last chance to see it.”

Such figures are rich reward for the lengths Bray went to to persuade owners to part with their precious Goyas. He first had the idea in 2001, but it became a full-blown obsession after he got the go-ahead in 2005. He even learned to shoot as a way of better understanding the hunting-addicted painter – and to hobnob with the Spanish aristocrats who own many of Goya’s masterpieces.

“Spanish aristocrats love to shoot, so it was a very good way to penetrate a society that would otherwise be closed to me,” Bray told a recent National Gallery lecture. “It was very useful in getting two wonderful portraits which belonged to the heirs of the family of the Count of Fernán Núñez.”

Speaking to the Guardian, Bray adds: “It wasn’t as if they said ‘if you shoot five partridges you’ll get one Goya, but if you get 10 you’ll get two’, but it was a way of making conversation.”

Goya himself used shooting to grease the commissioning of the very paintings Bray hunted down. “He went shooting with the Infante Don Luis, the king’s younger brother, and one of Goya’s key patrons. Apparently he was a better shot than Don Luis,” Bray says.

The curator also skilfully used the economic downturn in Spain to get access to some of Goya’s other works. “Quite a few Spanish families are having a hard time economically, which means some pictures have emerged that haven’t really been seen in public before. One of those of was the Don Valentín Bellvís. It would not have surfaced had the family not needed to sell it.

“It came up on the market in 2012. I was allowed to see it by the curator of a private collection who bought it and they very kindly reserved it to be shown at the National Gallery.”

He adds: “There is also a wonderful picture of Charles III in the first room, which hasn’t been seen in public for a very long time. I think the owner was pleased to insert the picture in the exhibition because it’s a good thing to showcase what you have in case of any future need.”

Others owners took more persuading. Bray was repeatedly told there was no way that the Hispanic Society of America would part with their prized portrait of the Duchess of Alba in black. A 1909 will by the society’s founder stipulates that it can never be lent.

But the appointment last April of a new chairman of trustees gave Bray an opening. Philippe de Montebello wanted to raise the profile of the society’s collection, which he felt was unfairly overlooked because of its out-of-the-way location on New York’s 155th Street.

Now, the Duchess of Alba is the centrepiece of the National Gallery show. But look closely at the caption and you’ll see directions to the Hispanic Society – one of the loan conditions negotiated by Bray.

Bray didn’t have it all his own way. He would love to have included Goya’s Countess of Chinchón, but the painting is jealously guarded by Madrid’s Prado museum. “There’s no way that she could be lent because the director of the Prado is completely in love with her and has vowed that she will never leave,” he says.

And when the flamboyant socialite the 18th Duchess of Alba died in 2014, Bray confesses to being “slightly annoyed” because her death represented another missed opportunity to bag another celebrated Goya.

“I was hoping she would understand why she would have to lend the Duchess of Alba in white.” Another family will stipulated it should never leave Spain. “I was hoping that because the Duchess had a few British titles we could argue that Britain was an extension of Spain,” Bray jokes.

The biggest disappointment was the refusal of Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum to loan Goya’s Don Ramón Satué. Bray is still smarting: “It was the only picture I wished that could have come, but I was told it was too fragile to travel. It is one of the amazing late portraits of 1823, the height of a liberal regime, and in that portrait Goya expresses a great sense of artistic freedom. I tried my best and I was a bit upset as it would have been a unique opportunity to see that picture in this kind of show.”

But overall Bray is very satisfied with the exhibition, even if it does have to come to an end. “Many times I was told: ‘are you sure you just want to do the portraits?’ But I was stubborn about that. I really wanted to see if the story of Goya’s career, life, moods, friendships, everything could be captured through the portraits, and I’m relieved to say it really works.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.