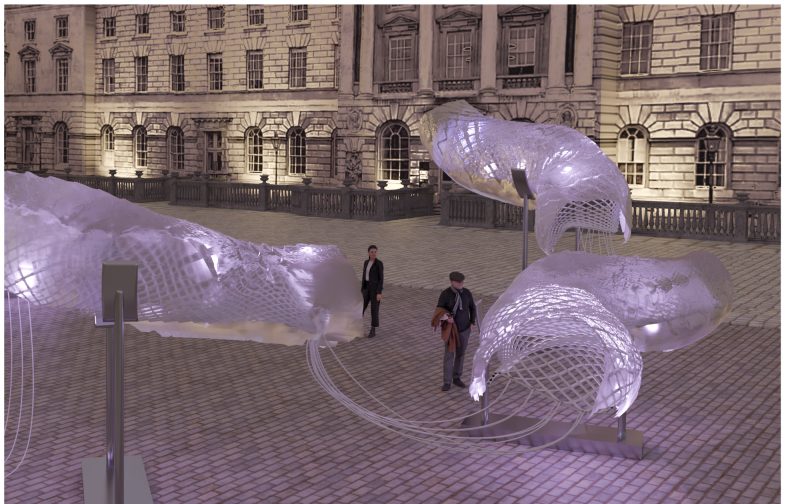

Plagiarism in progress? Karamay, in China’s Xinjiang region, is set to debut a public sculpture that resembles Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate. Photograph: AP

There isn’t much room for ambiguity. It is clearly Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate, the bulbous monument in Chicago known as the Bean, whose shiny metal surface reflects the sky in ever-changing ways.

Except this one is not in Chicago, and it is not by Kapoor. It has been built in the Xinjiang region of China in what appears to be an insouciant act of plagiarism.

The British sculptor is livid. “It seems that in China today it is permissible to steal the creativity of others,” Kapoor raged. “I feel I must take this to the highest level and pursue those responsible in the courts … the Chinese authorities must act to stop this kind of infringement and allow the full enforcement of copyright.”

The sculpture in the town of Karamay and the outrage about it raises fascinating questions. Why would a city in China think it could just knock up a copy of a living artist’s work without permission? Is this a malign act, or a magnificently naive one? Do people in the west make too much of the rights of the individual author?

William Hogarth would sympathise with Kapoor. The great 18th-century artist was so frustrated by pirated editions of his prints that he successfully lobbied for a British copyright act, known as Hogarth’s Act. The Engraver’s Copyright Act was repealed by the Copyright Act 1911.

The right of artists and authors to not have their work copied wholesale is a result of a commercial market in culture: Hogarth was one of the first artists to sell his work in the open marketplace. Today, every work of art in Europe, the US and many other places is someone’s property, and protected as such.

Are the rules different in China? Kapoor’s case is not the country’s first; copycat culture is rife in art and architecture. And it extends to music, too. Fans of Frozen were troubled, or amused, when they heard how remarkably familiar the “new” Beijing Winter Olympics anthem was to the film’s song Let It Go.

Does China simply have different attitudes to creativity? Does it believe less in the Romantic idea of artistic genius? It is nonsense to stereotype contemporary Chinese culture in this way. The creative individual has been at heart of Chinese art for a long time. Painters and poets of the Song dynasty, during the 12th century, were celebrated as distinctive creators at a time when European art embodied the labour of anonymous artisans and scribes.

There’s no reason to think that China placed a low value on the creative individual – until the 20th century, that is.

When Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution in China in the 1960s, young zealots were encouraged to root out intellectuals and elitists. Writers suffered along with anyone else, such as schoolteachers, who could be identified as an elitist. The Cultural Revolution undoubtedly attacked the idea that individual creativity should be celebrated or protected.

Andy Warhol perceptively identified Mao with the idea of the copy in his silkscreen portraits of the communist leader. Today’s China is remote from the one Mao wanted to create – economically, at least. But as Ai Weiwei keeps reminding the world, it is far from a democratic state. And perhaps now the ghost of Mao is smiling at Xinjiang’s mockery of bourgeois western artistic values.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.