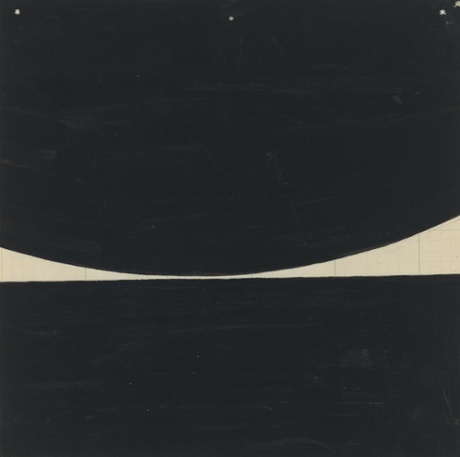

Reve, 1999 © 2015 Bridget Riley. All rights reserved, courtesy Karsten Schubert, London

Bridget Riley is the most important British painter of the modern age. Bacon? Freud? Hockney? None of those famous men took hold of the language of painting and remade it as she has. Most of the artists we are nationally proud of are sideshow performers who dallied with figuration long after it was blown apart by Jackson Pollock. Abstraction is the true destiny of modern painting and Riley and Howard Hodgkin are Britain’s two great living exponents of it. If Hodgkin resembles a poet, Riley is more like a scientist. In the 1960s she revealed a revolution hidden in the human eye.

To look at Riley’s 1964 painting Crest is to be sucked into a dazzling shimmering superstring universe. What has happened to reality? It has become a rushing cascade of black and white lines, warping in unison. The effect of this wave motion is to make the painting, as you approach it, move and expand. The brain cannot decipher what the eye sees. Instead of lines on a flat surface you experience a vertiginous plummeting waterfall of three dimensional space.

People were of course trying all kinds of things to change their perceptions in 1964. As Danny the drug dealer explains in Withnail and I, “You have done something to your brain. You have made it high … Why trust one drug and not the other? That’s politics, innit?” That politics pervades Riley’s paintings not just in their psychedelic belief that we must see reality anew, as if for the first time, but also in their technocratic conviction that science can achieve this. Instead of a pill, she uses lines. Riley’s art is all about lines that cavort and dance, and lead the brain into their crazy pirouette.

She paints like an engineer of human minds. The colours she sends streaming through space are carefully planned to tease and unfix us. The loveliest part of her exhibition at the De La Warr Pavilion is a selection of drawings in which she precisely and exquisitely maps out on graph paper the exact patterns she wants to paint. When Riley later met the art historian EH Gombrich, whose famous book Art and Illusion is a study of how we see and represent reality, they got on famously. Although she has no scientific training her art – as Gombrich, who generally distrusted modern art, recognised – is a serious investigation of the nature of perception.

To understand why Riley is such a huge original you need to compare these drawings – for instance Untitled (Right Angle Curve) (1966) which plots a typically eye-flummoxing whoosh of black lines – with the great American abstract painters who had transformed art after the second world war. The open, expansive work of Pollock and Barnett Newman speaks in a grand way to the soul. Riley’s graphs laugh at the very idea of a soul. Speaking to the soul? It’s optics, man. You do something to your brain. It’s not a romantic mystery. It’s doctoring the eye.

Riley took on the greatest and most revolutionary art of her time and turned its assumptions upside down. Revelation is not a rare attainment available only to a spiritual elite, her paintings assert, but a democratic right that science can deliver. We all see the same way and we can all have our minds blown wide open by the same optical effects. Not one of Bridget Riley’s paintings from the 1960s and 70s in this exhibition fails to work that magic. You don’t passively contemplate these paintings. You are changed by them. The world alters its nature. Flat surfaces become mountain ranges, rolling rivers, waterfalls. The space in front of the picture and behind it seems to vibrate, grow, shrink and twist.

Colours made their entry, adding to the intoxicating mayhem, as the 60s crested towards the 70s. Spending time with Riley’s painting Song of Orpheus 3 (1978) is like visiting the Alhambra drunk. Her feel for pattern and sensuality of colour is delirously Moorish.

![Bridget Riley, Untitled [Turquoise and red curves]_1968_ The Trustees of The British Museum, London BridgetRiley Please credit Bridget Riley 2015, courtesy Karsten Schubert, LondonPress](http://static.guim.co.uk/sys-images/Guardian/Pix/pictures/2015/6/11/1434035755583/6dacce7a-c3dd-4fd7-a937-8dc97dd6f692-460x286.jpeg)

But a few years after this, the wave breaks, hits the shore and rolls back. Riley is a revolutionary artist, and revolutions come to an end. When I say she is our most important painter I mean she has transformed and reimagined what painting can be. She did this in an age of radical change and optimism. It is impossible not to see Riley as a visionary of the 1960s whose art unfolds a new and liberating way of seeing. Forget pop art. It is Riley’s sublime “op art” that really expresses the hopes and possibilities of the 60s and their tie-dyed 70s aftermath.

It is tempting to see her later art as expressing its time, too. This exhibition is called The Curve Paintings 1961-2014 and it follows one kind of line – a curvy one – through Riley’s art over more than five decades. But in the 1980s the curve broke – literally. Instead of endless universal waves her later paintings use more jagged, fragmentary and cubistic forms. The flow ceases. She does not gather you in but invites you to look. You stand apart, contemplating formidable and beautiful – but no longer dynamic, delirious or mind-blowing – colours.

Riley’s early paintings are American in their Pollock-like, rollercoaster sense of space, and the way they are not designed like pictures within a frame but seem to invisibly carry on over the edges of the canvas – what American critics at the time called “all over” painting, and rightly saw as tremendously liberating. Her later ones are proudly European. They grandly enjoy their place in the history of modern European art, and consciously evoke the broken light of Seurat. While her early works have a Manhattanite sense of urgency, her later ones make me imagine her communing with Matisse after a good lunch in Provence.

It strikes me that Riley’s art in the 1980s lost its belief in change, revolution and oneness. Didn’t we all? It scarcely matters. Bridget Riley is Britain’s Jackson Pollock. Go tell that to the masters.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.