It has been nearly 50 years since there has been a full retrospective of Barbara Hepworth’s sculpture and drawings in London. In the time since then, arguably Britain’s greatest woman artist has been claimed both by her native Yorkshire and her adoptive Cornwall. The Hepworth gallery museums in Wakefield and in St Ives are wonderful homages to her life and practice, but in rooting her so comprehensively in the place she grew up and in the place where she lived and died, visitors are perhaps in danger of denying Barbara Hepworth her due in the pantheon of international 20th-century art.

At least that is the view of Chris Stephens, lead curator of modern British art at the Tate and the driving force behind the Hepworth show that will open at Tate Britain this month. Right from when she first visited Italy in her early 20s, Stephens suggests, Hepworth was near the forefront of European modernism. When she established her home and studio in Hampstead, London with painter Ben Nicholson before the war, they quickly became the focus of a group of artists that included Piet Mondrian and Naum Gabo, as well as visiting Picasso and Constantin Brancusi in France.

“One of the reasons we called the exhibition Sculpture for a Modern World,” Stephens tells me, “was that it was not just modern sculpture Hepworth was engaged with, but modern thought. That movement in the 30s was about freeing art from everyday reality. They came together in response to the advance of nationalism, initially through letters and journals and then literally, as everyone flees Europe and ends up in Hampstead for a while.”

Though she is sometimes viewed in relation to male artists of the period, in particular Nicholson and Henry Moore (her Yorkshire contemporary), Hepworth’s career insists on her standing alone. “If she and Moore had not been from the same county and about the same age then I don’t think they would ever have been compared to each other,” Stephens says. “A lot of his work is dark and about trauma and so on. Hers is not aspiring to be grounded and worldly; it is utopian, in search of perfect forms.”

The exhibition will show how that idealism and political engagement was challenged both by the war and by the demands of Hepworth’s personal life. She was the mother of four by the time war came (including five-year-old triplets with Nicholson). The original move to St Ives was more like a desperate evacuation, and for many years afterwards Hepworth fought for the time and space to pursue her vocation. All the time though, Stephens suggests, “she was this international figure thinking what the world might be, not just a woman living in Cornwall making sculpture inspired by the sea. Even during the second world war, it was as if she was running a think tank with a view to creating ideals that fed into the world.”

In the years after that, until her untimely death in a house fire in St Ives, apparently caused by falling asleep with a cigarette, aged 72, Hepworth pursued a singular vision that sought always to find underlying harmonies in the postwar world. She revolutionised the possibilities of carving by insisting on complex interiors to her work, as well as smooth exteriors, overcoming personal tragedy through her art. When she looked back on her life towards the end of it, Hepworth suggested that it seemed to her that “the years seem to fall naturally into six divisions”. If that were the case then the six pieces of sculpture here look a little like a short biography in wood and stone.

Doves (Group) (1927)

Doves (Group) is Barbara Hepworth’s earliest surviving stone-carving. She made it in Italy having travelled there alone, aged 21, after studying in Leeds and at the Royal College of Art in London. She was, at the time, sporting an abrupt flapper’s bob, quiet confidence in her skills and radical ideas about how she might help to transform European sculpture. She was a long way from 1920s Wakefield. She met another British sculptor in Italy, John Skeaping, and after a short love affair married him in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence.

The newlyweds kept doves. The image itself referenced a sculpture by Jacob Epstein, a dominant figure in British sculpture at the time, though Epstein’s work was more stylised and overtly sexual in spirit, one dove mounting the other. Hepworth’s version of the paired birds was both more intimate and more closely observed. Looking back on it in later life, she suggested it as the first instance of what became a lifelong obsession: “works of two forms related to each other in a kind of tender relationship … searching for this kind of emotional impact of the two together”.

She was studying in Rome, with Skeaping, under the Italian master carver, Giovanni Ardini. A remark he made fascinated her: “marble,” Ardini said, “changes colour under different people’s hands”. The implications of that thought helped Hepworth to decide that her method should not be about dominance over her material – stone or wood – but rather “an understanding, almost a kind of persuasion”. She and Skeaping were at the forefront of a movement to re-emphasise the craft and skill of the artist’s hand – unlike many pre-eminent Victorian sculptors they were carvers not modellers – and in this instance Hepworth left the base of her sculpture roughly hewn to show how the form had emerged.

She had her first exhibition – which was a success particularly among collectors of ancient Chinese carving – in June 1928 with Skeaping, and the following year their son Paul was born. “At this time,” Hepworth said, “all the carvings were an effort to find a personal accord with the stones or wood which I was carving. I was fascinated by the new problem which arose out of each sculpture, and by the kind of form that grew out of achieving a personal harmony with the material.”

Mother and Child (1934)

‘There is an inside and an outside to every form,” Hepworth once wrote, and sometimes, “they are in special accord, as for instance a nut in its shell or a child in the womb.”

When she and John Skeaping returned to London in 1927 and set up home in Hampstead, they became part of a circle of artists closely in touch with the European modernism of Picasso and Brancusi. Among this group was the young British abstract painter Ben Nicholson. Hepworth and Nicholson fell in love and eventually moved in together. They lived and worked in a tiny flat and studio in Parkhill Road, Hampstead, art becoming almost a joint enterprise, with Nicholson incorporating Hepworth’s distinctive profile in his drawing, she finding inspiration from his idealised abstractions, and each of them obsessively photographing details of the other’s hands and eyes at work.

By 1934, when Hepworth made Mother and Child, one of several linked sculptures, she was pregnant with what turned out to be triplets. Unlike her Yorkshire contemporary, Henry Moore, who typically made mother-and-child pieces as single figures, Hepworth conceived of her maternal works as two separate bodies, intimately involved. In another of the series she depicts a void in the mother’s abdomen, where the infant had been. She is already a mother, and about to become one again. This sculpture is on a very tender scale, only 17cm high.

Hepworth gave birth at home in their small basement flat. “It was,” she later recalled, with some understatement, “a tremendously exciting event. We were only prepared for one child and the arrival of three babies by six o’clock in the morning meant considerable improvisation for the first few days…”

When she started carving again in November 1934, her work, she said, seemed to have changed direction, “although the only fresh influence had been the arrival of the children”. All traces of naturalism disappeared. She was, she said, absorbed in the expression of the texture and weight and the tensions between forms, searching for “some absolute essence in sculptural terms giving the quality of human relationships”.

In an interview with the Observer in 1964, Hepworth was asked whether domestic demands had ever frustrated her, or got in the way of her legendary capacity for work, and she recalled this period with a laugh: “Well, of course, I had triplets by Ben Nicholson, and then it was do or die! But being a mother enriches a sculptor’s experience. I decided I must do some work each day. It went on in my head even when I was doing the chores. The result was fewer sculptures, but I believe more triumphs. I never resisted things. If something in the kitchen was burning, or a child crying, I attended and continued my carving without feeling resentful…”

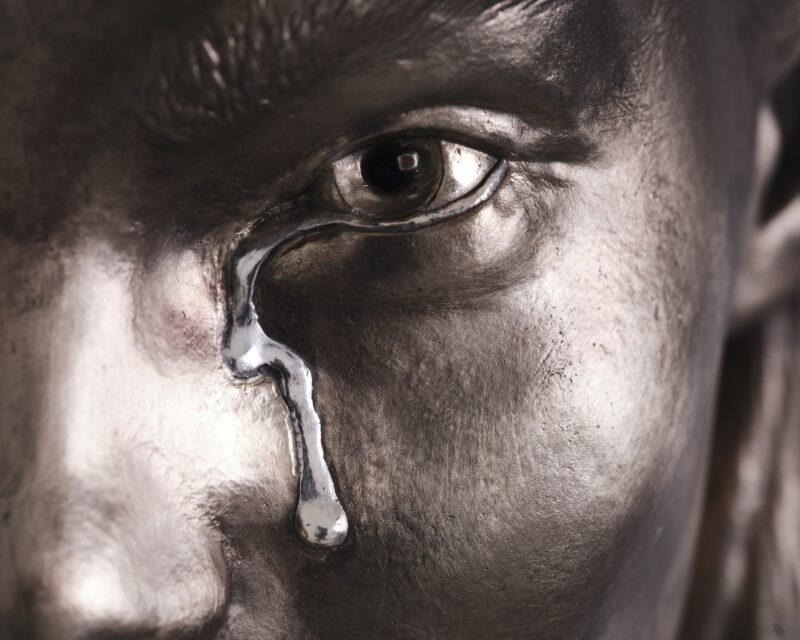

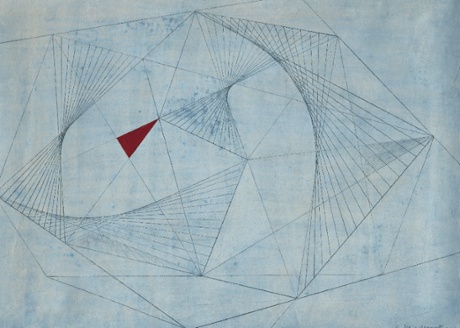

Red in Tension (1941)

As political uncertainty in Europe increased in the mid-30s, many European artists, including Piet Mondrian and Naum Gabo, sought refuge in London and set up studios around the corner from Hepworth and Nicholson. The artists were united in opposition to the rise of fascism, determined to make a more harmonious, optimistic expression of human possibility. Hepworth was exploring idealised forms, in poised relationships; inspired by Mondrian, she wondered about incorporating colour into her sculpture.

Such questions were shattered by the outbreak of war in 1939. The Hampstead group scattered, Mondrian to New York, and Nicholson and Hepworth to St Ives in Cornwall. They were desperate for many things, including money. “From late 1938 until war was declared,” Hepworth recalled, “it became increasingly difficult to sell a painting or a sculpture and make a bare living. At the most difficult moment of this period, I did a maquette for the first sculpture with colour, and when I took the children to Cornwall five days before war was declared I took the maquette with me, also my hammer and a minimum of stonecarving tools.” Nicholson followed; their studio and some of the work they had made together was later destroyed in the blitz.

At first, in Cornwall, they stayed with friends. Early in 1940 they rented a small house in St Ives and for the next three years Hepworth was unable to carve at all; she had neither the means, nor the time. Instead, at nights, when the children were finally asleep, she started working on a series of drawings, working through ideas that she was unable to make in three dimensions. The forms were hollowed out: interior spaces seem to have become more valuable to her. They contained colour and string-like elements, gestures toward mathematical harmonies. The anxiety of their lives was resolved into something tense and restrained.

Hepworth is rarely thought of as a war artist in the same way as her contemporaries John Piper or Graham Sutherland were. But her drawings no doubt represented a response to the horrors every bit as valid as their more graphic and direct depictions. She clung to the timeless in a world of insistent news. “I remember how,” she later said, “during the war, a bombing once led to the accidental unearthing of a carved Anglo-Norman capital in which the artificial colouring of the stone had somehow been preserved. I was able to see how the cavities of the reliefs had once been coloured with a bright terracotta red, and this was exactly the kind of effect that I too had been seeking from 1938 onwards, in some of my own works. What I had considered an innovation thus turned out to be a lost tradition in English sculpture…”

Pendour (1947)

The postwar years in St Ives saw Hepworth return to carving. She took her inspiration from the landscape around her and her place within it. The ideas for colour that she had sketched out in the early hours during the war, and of interiorised forms, became a reality in the woodcarvings she made in the late 40s. The wood itself she foraged for or purchased locally. Many of the pieces took inspiration from a particular coastal contour that Hepworth explored in walks from St Ives. Pendour Cove is near the village of Zennor. In Cornish myth it is the scene for a mythical encounter between a young man and a mermaid he charms from the water by singing.

Hepworth, it seems, sought some comparable epiphany in this work, an escape from the realities of 1947. She wanted to feel not a spectator in the landscape but a part of it, as grounded as trees or rocks, and to convey that experience in her carving. “What a different shape and ‘being’ one becomes lying on the sand,” she wrote, “with the sea almost above, from when standing against the wind on a high sheer cliff with seabirds circling patterns below one; and again what a contrast between the form one feels within oneself sheltering near some great rocks or reclining in the sun on the grass-covered rocky shapes which make the double spiral of Pendour or Zennor Cove …”

The sculptures, which she also photographed set against the Cornish skyline, were a celebration of the idea that the artist exists within the visible scene and not apart from it. The sculptures were not an expression of the observed landscape but of the act of observing it. “There is no landscape without the human figure,” Hepworth wrote, as a kind of manifesto. “It is impossible for me to contemplate prehistory in the abstract. Without the relationship of man and his land, the mental image becomes a nightmare.”

At the same time as she was making these sculptures, Hepworth befriended a surgeon, Norman Capener, whom she had met when her daughter Sarah developed a bone infection at the end of the war, and who had invited her to watch him work, often doing reconstructive surgery. She saw in the operating theatre a metaphor for her own practice in searching for ideal forms out of the postwar rubble. And she saw in the dexterity and flow of the surgeon’s hand movements an affinity that she tried to capture in beautiful drawings, and which she seemed to embody in her sculpture. She became absorbed in the spiritual connection between mind and hand, internal and external, and sought to dramatise it in her remade Cornish fire logs.

Curved Form (Delphi) (1955)

In the early 1950s, Hepworth fell into a debilitating depression brought about by separation from Nicholson, and the death of her first son, Paul, an RAF officer who was killed in a plane crash. In an effort to shift her out of her unproductive despair, her close friend Margaret Gardiner went with her on a trip to Greece to look at classical sculpture and carving.

The journey had the hoped-for restorative effect. She kept a journal of her travels in Greece, but one site – Delphi – proved too overwhelming for her to put into words. It was only a decade later that she noted how, “on a fair and glorious morning I managed to escape some 400 people and ascend the hill alone and in silence. Standing alone in the stadium, alone below Olympus, I felt at ease both physically and spiritually. This experience of being part of the plain of Itea and totally alone did perhaps justify my existence. To describe the day would dissipate the visual memory. Instead I hold it secretly to sustain me.”

On her return to England, Gardiner helped Hepworth satisfy another of her ambitions – to return to carving tropical hardwoods, unavailable since the war. Through contacts in Africa Gardiner asked for some samples of Nigerian guarea wood to be shipped; in the event 17 tons of it, huge sections of tree trunk, arrived at Tilbury Docks and were then transported to St Ives, and Hepworth’s studio.

“The difficulties were immense,” Hepworth noted. “The smallest piece weighed ¾ of a ton. The largest weighed two tons. It became a drama in St Ives. Each piece of wood had a giant fork driven into it, and a huge metal ring (no doubt to enable elephants or cranes to lift each piece), but in the cobbled streets of St Ives we had to manhandle each piece. The logs were the biggest and finest I had ever seen – most beautiful, hard, lovely warm timber. Out of these ‘samples’ I carved Corinthos’, Delphi, Phira, Epidauros and Delos’. I was never happier.”

Using the inspiration of her Greek adventure, Hepworth dived into the wood, tunnelling through it, almost as she had mined grief for her son. She was relieved to have come through the tragedy and to have found the inspiration to work again. She left the marks of her great physical endeavour on the interior surface of the wood, though the outsides were burnished like conkers.

In a letter to a friend, she wrote of the experience: “Already one of the largest logs is taking shape – a great cave is appearing and I have tunnelled right through the 48 inches and daylight gleams within it. It is terribly exciting to have such enormous breadth and depth. When I have finished perhaps I shall be able to get inside it. Now I want to carve them all at once…”

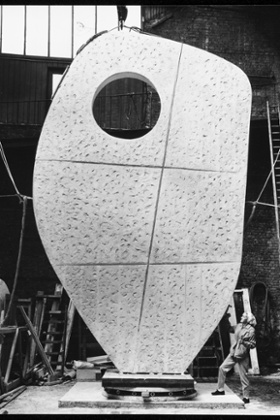

Single Form (1961-4)

By the end of the 1950s, Hepworth’s standing as a significant international artist was firmly established. In 1961 she was commissioned by the United Nations to make a memorial to secretary-general Dag Hammarskjöld who had died in a plane crash earlier that year. Hammarskjöld had met Hepworth and been a collector of her work, and the commission, which would stand outside the United Nations Secretariat in New York would be a crowning achievement for her.

She had never before worked at the monumental scale required, and in an effort perhaps to make the form more familiar to her she sketched it first, in actual size, on the chequerboard floor of one of her studios, a former dance hall in St Ives. Hepworth was rarely a willing speechmaker, preferring to let her art do her talking for her, but on the occasion of the unveiling of her sculpture in 1961 she was required to say a few words. Having lived through two world wars, the United Nations was symbolic of her lifelong faith in the possibility of higher ideals, based on international cooperation. As a woman of the left, some of that optimism had been damaged by the events in Hungary in 1956; by 1961 the UN looked a lot to her like the last best hope. “The United Nations is our conscience,” she said, “if it succeeds it is our success. If it fails it is our failure. Throughout my work on the Single Form I have kept in mind Dag Hammarskjöld’s ideas of human and aesthetic ideology and I have tried to perfect a symbol that would reflect the nobility of his life, and at the same time give us a motive and symbol of both continuity and solidarity for the future…”

The success of Single Form led to many more commissions in bronze for Hepworth, more public statuary. She continued to put in her eight-hour shifts, “to play it hard” at her St Ives studios, working on those large-scale public commissions, and returning to her first love of carving marble on a more intimate scale.

Although by then international sculpture had become many other things apart from carving – including welding and salvage and (if you were Gilbert or George) standing still – her reputation was secured. She remained faithful to the work above all else to the end – cutting her son Simon from her will after she discovered he had sold a sculpture she had given him. In one of her last interviews, she described a perfect day at her Porthmeor studio watching the Atlantic rollers carving the shoreline in these terms:

“The strokes of the hammer on the chisel should be in time with your heartbeat. You breathe easily. The whole of your body is involved. You move around the sculpture, and the whole of you, from the toes up, is concentrated in your left hand, which dictates the creation…”

Hepworth worked like this most days, right up until the fire at her cottage in which she died in 1975, aged 72.

• Sculpture for a Modern World is at Tate Britain, London SW1, 24 June-25 October

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.