Shelf life … the contents of the hardware store bought by Gates. Photograph: Sarah Pooley/White Cube

When Theaster Gates won the £40,000 Artes Mundi prize in Cardiff earlier this year, he yelled, “Let’s split this motherfucker!”, and shared the money with the other shortlisted artists. It was a magnificent gesture on the part of the Chicago artist, whose entire project is committed to bringing people together. Gates wants to make the world a better place.

His is a project that begins at home, in the rundown South Side of Chicago where he lives. Trained as a potter and an urban planner, Gates goes back to fundamentals in his art, and much of his time and work is dedicated to the urban renewal of his community. Quite what he is doing showing at White Cube gallery in Bermondsey, in the shadow of Renzo Piano’s Shard of Doom (and in a neighbourhood that’s gone from urban blight to the £20 pub lunch in the blink of an eye) is moot. Gates is aware of the contradiction; he operates both inside and outside the commercial art world. His projects – which include leasing or buying abandoned, wrecked and flooded buildings, then refurbishing them as community centres, libraries, cinemas and other projects – need cash. He’s as interested in communities as in the immunity to poverty that a successful art career brings.

Commercial galleries need products to sell. Gates’s Freedom of Assembly is a play on modernist manners and devices, and on the kinds of things a gallery such as White Cube shows. This is not necessarily a contradiction. Little red squares and rectangles, black chevrons, lozenges, rhomboids and stripes jump about across a big tan field. The whole thing looks like an old-fashioned kind of geometric abstraction. It’s almost like a fanciful music score. The music, if there were any, would be all squeaks and bumps with scattered, pattering rhythms. The squeaks would be the sound of basketball sneakers on a wooden floor, the rhythms a ball bouncing, augmented by the noise of running feet and bodies sliding, slipping and colliding.

Gates’s Ground Rules are a pair of large works that might almost be paintings: they’re made from the varnished wooden floor of a high-school gymnasium, with all its coloured markings for different sports, removed from the gym and reassembled, out of order, as a pair of handsome wall panels. The worn markings have the look of marquetry, or enamel inlays, or a mid-century modern painting that has seen better times. Age has lent the work a certain patina, a memory of use.

And here is an arrangement of forks, the kind used on forklift trucks. They climb the wall like a Donald Judd sculpture, in two rows. Nearby, another pair of forks hold up a beautifully carpentered pallet of glazed building bricks. If these are a reference to Carl Andre, another sculpture nearby is a direct take on Brancusi’s Endless Column, but made from cut sections of pegboard. Gates recently acquired an entire hardware store in Chicago, and the pegboard probably came from there. Faded old price stickers decorate the wood. More stuff from the hardware store is arranged behind glass in a display cabinet – the remains of stock displays of cup hooks, hinges and padlocks. They’re a sorry sight.

In the biggest space, Gates is showing more paintings – except they’re made from various roofing materials, asphalt membranes, roofing paper and fabric substrate, cleated rather than tacked on to their supports. And, instead of paint, he’s used gloopy tar and liquid rubber, and painted the surfaces as though he were waterproofing a flat roof. This was the job Gates’s father did, before he hung up his tarring bucket and swab brush at the age of 80, bequeathing the everyday tools of his trade to his son. The paintings look like empty landscapes and brooding black skies, as well as the tarred roofs they emulate. They remind me of Antoni Tàpies, as well as lots of muscle-bound painters who mistake brutal materials for honest work.

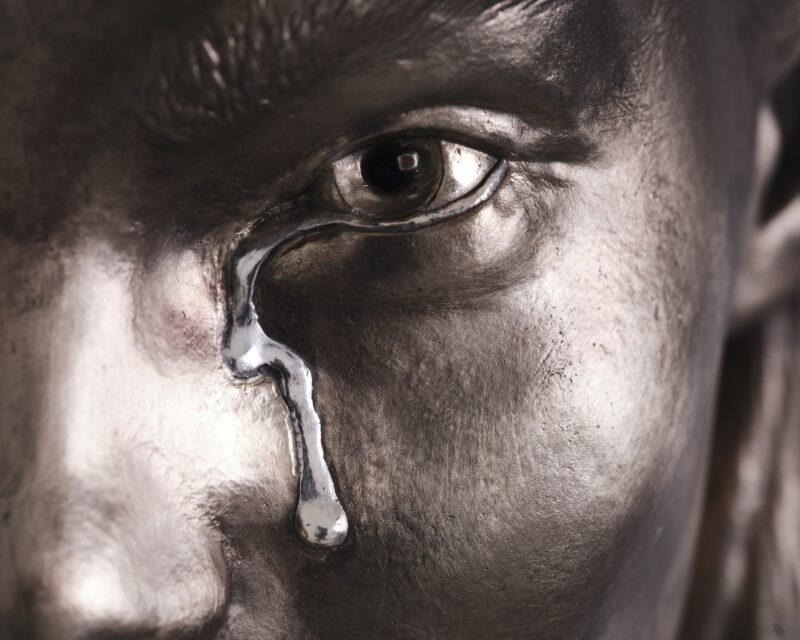

These kinds of plays are pretty familiar gambits. We are all used, I think, to seeing what looks like abstract art in the everyday – in a painter and decorator’s unfinished tasks or a builder’s rendering of a wall, in a pile of bricks. Gates’s thrown and glazed ceramic pots, mounted on rough plinths of reclaimed wood, are better. Their scale feels right. Apart from one or two left bare, most have been dipped in tar or black rubber, or swathed in greasy tarpaper – presenting them less like a wrapped gift, more like something bound and desecrated.

The individual pleasures of the clay shapes are hidden, swaddled, tarred. Sometimes you glimpse a flash of colour and shine beneath a break in the black stuff. A tiny rhinestone, like an earring, glints from the surface of one vessel. These are all playful in a way the painting substitutes aren’t. They’re like personages under duress.

Completing the show, a number of small cast figures stand around on the gallery floor. They look as if they’ve been cast from some anthropomorphised industrial object. I wish they were more affective and had more presence than they do. Somehow the poetry feels trowelled-on.

• Theaster Gates: Freedom of Assembly is at White Cube, London, until 5 July.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.