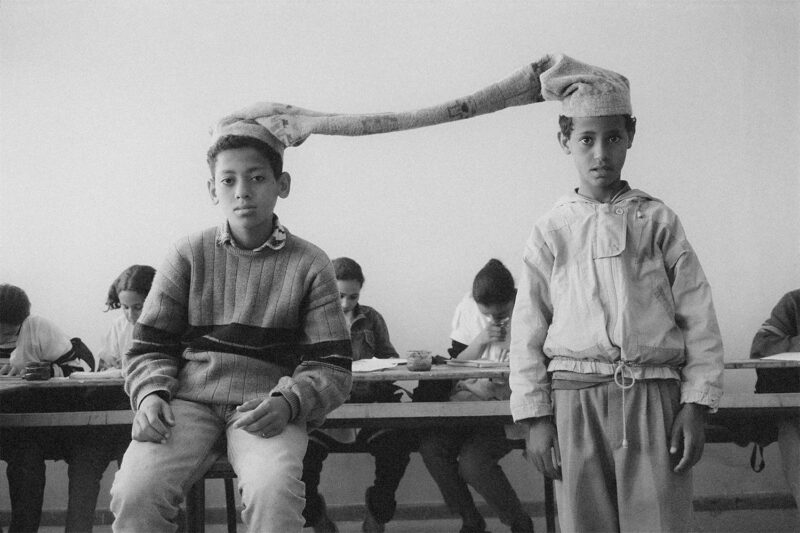

Standing tall … detail from Untitled #3, from the series Ponte City (2008), an obsessive cataloguing of life in the highest residential tower block in Johannesburg, by Mikhael Subotzky & Patrick Waterhouse. Photograph: courtesy Goodman Gallery

As always, this year’s Deutsche Börse photography prize exhibition gives both a glimpse of the future and a nod to the past. One floor comprises two artists, Zanele Muholi and Nikolai Bakharev, who shoot in black and white for what might be called traditional purposes – socially engaged portraiture and low-key observation. Another floor features the work of Viviane Sassen and Mikhael Subotzky and Patrick Waterhouse, who have nothing in common but a desire to push the boundaries of the medium.

Moving between floors is like walking from one world into another.

In terms of sheer ambition, Subotzky and his collaborator Patrick Waterhouse would win any prize hands down. Their multimedia project, Ponte City, shot in and around the tallest residential tower block in Johannesburg, is a work of obsessive determination: every single window and door of the 54-storey building has been photographed, then presented in tall Perspex towers that echo its scale and communal intensity.

Originally built during apartheid as a heavily guarded dream residence for rich whites – “Live in Ponte and never go out” was one of its advertising slogans – the building has since had several lives. After a failed attempt at refurbishment, it now houses locals and immigrants from across Africa.

Subotzky and Waterhouse began their meticulous project of social excavation in 2007, while the tower block was being refurbished, and they continued photographing floor by floor (and room by room, and window by window) for six years. It’s a monumental series, both as a heavyweight book and an exhibition. Here, though, it seems squeezed into a space that barely contains its epic reach. But its ambition is evident in the intriguing layout, which merges the epic – large-format portraits of life inside and outside the tower – with evocative ephemera – letters from residents, pieces of fabric, found photographs laid over Subotzky’s own images of the same spaces. A vitrine holds a copy of the intricately designed photobook, which is a work of art in itself.

Next door, Viviane Sassen’s work also seems squeezed into a too-small space, which she has divided diagonally with a wall on which a videowork plays – a poem by Maria Barnas rendered in sign language by two floating arms and their corresponding shadows. Sassen is a poet of shadows, but also of vivid colour and increasingly formalist geometry. Sassen’s series Umbra was inspired by her love for Malevich’s Black Square painting (perhaps the ultimate formalist expression), and, as with all her work, by her childhood in Kenya. Sunlight in a Sassen photograph tends towards hyperbrightness, and shadows towards pitch black. People and things emerge mysteriously out of, or are grounded in, this juxtaposition of extremes, with their shapes often as oddly geometric as manmade sculptures.

More and more, as she moves away from fashion photography, Sassen’s work seems like sculpture made with a camera and the most concentrated available light. In one composition, two similar black shadows frame a sunlit highway. On closer inspection, they turn out to be the silhouettes of two burqa-clad women. In another series, abstraction takes over as angular mirrors echo the reflections of coloured Perspex on sand. Each series has a title as mysterious as its pictures: Hurtling, Rebus, Axiom. When you approach Sassen’s work, you are entering her world, surrendering to her singular, often mysterious, imagination. Of the four, she is an artist who uses a camera purely for aesthetic reasons.

Downstairs, things take a turn for the monochrome. Nikolai Bakharev’s series of ordinary Russians at leisure is easily the most low-key work here. As such, it provides a breathing space. He began taking photographs in 1970, aged 24, at a time when, as catalogue essayist Olga Sviblova says, “the profession of photographer was considered on a par with that of manual labourer”.

Rejecting socialist realism for a more relaxed approach, Bakharev carefully arranged his subjects in fixed poses that denoted happiness or relaxation. His main territory was the beach – that most public and most intimate of spaces; a relatively “free” place where people shed most of their clothes and many of their inhibitions. Bakharev’s series, Relationship, was shot in the late 1980s and early 1990s, though it could have come from almost any time in the past 40 years. These determinedly casual shots are anything but: all of the people in them – loving couples, hugging children, entwined families – are acting out a sense of harmony that is both real and heightened. It is only when Bakharev’s camera moves indoors that the languorousness of his subjects attains a palpable, almost luminous, sensuality: a couple asleep in their underwear on an untidy couch; two girls smoking in a kind of blissful reverie, both aware of, and unfazed by, the photographer. These almost-snapshots have a cumulative power that is quite magical.

Alongside Bakharev, Zanele Muholi’s large black-and-white portraits seem inordinately stark and formal, arranged on the wall unframed and close together in grids. Muholi is an activist with a camera, a founding member of the Forum for the Empowerment of Women and of Inkanyiso, a forum for queer and visual media. The power of her portraits of the LGBTI community in South Africa resides in the stories behind them as much as it does in the starkness of the images. Those stories tell of suffering, struggle and often incredible personal bravery.

Made between 2006 and 2014, her series Faces and Phases is a merging of portraiture and first-person testimonies, many of which bring to life the extent of the discrimination experienced by her subjects – and the attendant violence inflicted on them by a deeply homophobic society. A video piece allows the women to speak for themselves and, as their stories unfold, the relatively straightforward portraits cannot help but take on a deeper power. The photography is another strand in Muholi’s gathering of evidence, though her book, Faces and Phases, seems a more compact and hard-hitting means of expressing her work than the display here. (Like Subotzky and Waterhouse, she has been nominated for a publication rather than an exhibition.)

There are many odd echoes in this shortlist show, not least the fact that it features two South African artists, Subotzky and Muholi, grappling with a still broken post-apartheid society. By what criteria one judges Muholi’s work against Sassen’s or Subotzky and Waterhouse’s against Bakharev’s is, as ever, anyone’s guess, and that dilemma highlights both the strength and weakness of exhibitions built around awards that are not themed by genre or purpose.

The problem of space – or, to be precise, the lack of it – seems acute this year, particularly in terms of the presentation of the Ponte City project. But there is much here to intrigue and surprise. For me, it’s between Subotzky and Waterhouse for ambition and Sassen for art.

• The Deutsche Börse Photography Prize 2015 is at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, 17 April to 7 June.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.