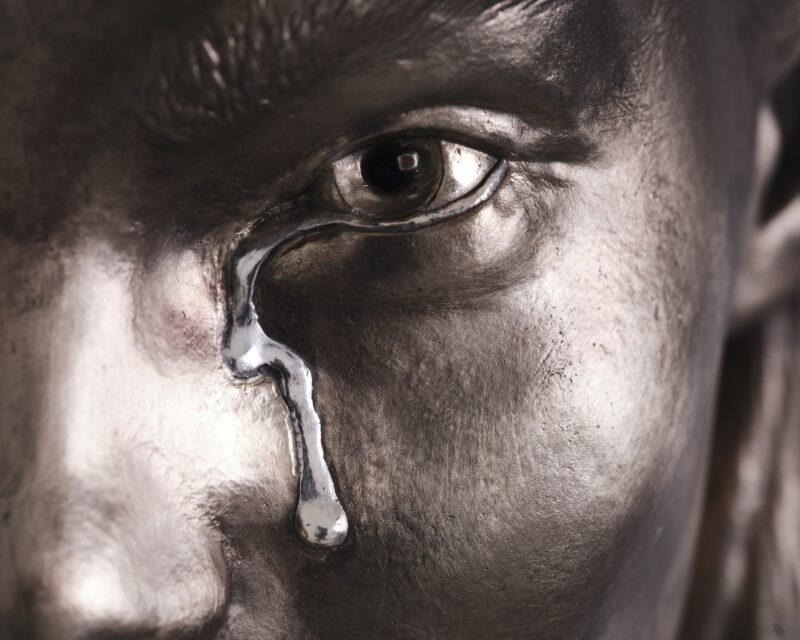

Thomas Longmore and John Hénk Elephant 1889 © Thomas Goode & Co. Ltd., London

Of all the outlandish objects in Sculpture Victorious – the majolica peacock, the emu-egg casket, the lifesize electroplated figure of Elizabeth I – the most needlessly elaborate is a salt cellar in the form of St George treading triumphantly on his dragon by the English sculptor Edward Onslow Ford.

To make this dapper little fighter with his shining sword and shield, Ford needed five different talents. He carved the head in ivory, metal-worked the armour, modelled the dragon in clay using a small fowl for proportions and then cast the whole thing in silver, before etching in the details. It is, at the very least, a technical feat.

But what else is it? That is the question irresistibly proposed through room after room of this undeniably peculiar show. What is this object, is it functional, decorative, or both, where did it go, what was it for? You could not guess, for instance, that the salt went in the dragon’s left wing, and the knowledge doesn’t enhance the art so much as encourage pity for the maid struggling to keep this overwrought curiosity clean without stabbing herself on that sharp little sword.

Sculpture Victorious brings out the best and the worst of a patriotic era. It is one long striving after something more stirring, ingenious, complex, inspiring: emotion embodied in strenuous form. Nymphs and vestal virgins, Arthurian knights and athletes wrestling serpents, the victorious soldiers of the empire and the kind-faced ladies who look down from charitable drinking fountains all over England: it is everything you might expect, interspersed with the weirdest of novelties.

An imaginary chess game – the size of life and taking place on what looks like an outsize funeral casket – between Elizabeth I and Philip II of Spain probably exceeds everything else for all-out kitsch, but it has strong competition from the Earl of Eglinton’s silver jousting trophy, an eye-searingly bright assembly of knights and damsels apparently ascending a helter-skelter.

If this seems almost risibly excessive, it is worth noting that the curators have a sense of humour too. Not for nothing is there a white elephant (porcelain, vast, beneath a jewelled howdah) positioned at the very centre of the show.

Still, this is an odd, not to say divided approach to showing art. On the one hand the curators seem well aware of the eccentricity – even the monstrosity – of some of the exhibits; on the other, they need to set these exhibits before us in order to advance their theory of Victorian culture. They want to show us a Britain in which sculpture surges in popularity as never before (and perhaps never since) – no matter what it looks like.

The first room gives the picture straight away. Here are busts of Queen Victoria in marble and bronze, but also in copper and cheap glass and in every size from deluxe to pocket, with economy editions for The Diary of a Nobody’s Pooterish clerks. The market for the monarch grew to staggering proportions, and with it the appetite for sculpture. The state commissioned mock-medieval statues for the House of Commons, along with job lots of patriotic monuments for town squares throughout Britain.

The citizens themselves bought fountains and figureheads through public subscription. And the middle classes could buy modest copies of major works – an athlete firing an invisible arrow at an eagle, say – through the use of a cunning invention that scaled down monumental pieces to fit the mantelpiece.

Victorians invented new technologies to replace bronze and marble with thriftier materials. The figure of the Earl of Winchester, on loan from the House of Lords, gets at least some of its tough force of personality from the weather-beaten face and the biceps clad in rusting chain mail, their colour the result of electroplating zinc with copper.

Marble was reproduced in Parian ware, a kind of porcelain manufactured by Minton; and the Parthenon marbles were copied for art schools and private collectors throughout the land in plaster, slate and electrodeposits on wood.

It shows; especially in the more extreme hybrids, such as the statue of Dame Alice Owen, founder of the eponymous girls’ school, whose alabaster head and hands have been cemented to her cast iron body so that she couldn’t look less like a human being (or even a sculpture).

Worst of all is Burne-Jones’s relief panel of gilded figures trying to rise out of their gesso paint, a sculpture that just wants to be a painting.

Almost everything here was made to make us marvel, literally in the case of the many objects created for the Great Exhibition or the Paris Exposition. There is a strong sense of competition in the air. The carver from Louth who produced the prodigious panel of ivy leaves growing over an old door, complete with moss, a slithering snail and a pair of partridges dangling from a desiccated piece of string all out of a single piece of limewood, is clearly competing with the 17th-century master of wood carving, Grinling Gibbons.

Yet Tate Britain’s claim that this is “a golden age for sculpture” is itself outlandish. It might be a golden age for commissions, and popularity, but the art itself is wildly variable.

The best work in this show is right at the start – unfortunately, for everything that follows: a bust of Queen Victoria carved in marble by Alfred Gilbert. Larger than life, with a powerful hauteur in its sombre features, the full melancholy of the ageing widow hanging heavy in the flesh, it is a stupendous work.

Gilbert didn’t get round to a crown, so that his queen seems even more human than all the others at Tate Britain. And there are many, for Sculpture Victorious is essentially a show of official art, a gathering of imperial propaganda from salt cellars to electroplated monarchs. Like so many of the objects themselves, it is a history lesson in figurative form, not about the pleasures of looking so much as learning.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.