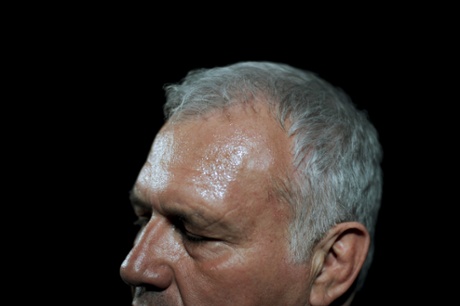

On Tuesday, a Belgian court found the Antwerp-born painter Luc Tuymans guilty of plagiarism, in his use of a photograph of the politician Jean-Marie Dedecker taken by Katrijn van Giel for Belgian newspaper De Standaard.

Tuymans is one of Europe’s leading and most influential painters. In Belgium, he is an often outspoken public figure. He held a mid-career retrospective at Tate Modern in 2004, and opens a new exhibition in London next week.

Throughout his career, Tuymans has used photographic source material as a basis for his paintings – images of hospital patients, archive portraits of national socialists and Nazis, Belgian seminarists, Ku Klux Klan leaders.

He frequently uses images he has photographed himself, using a Polaroid camera or iPhone, and often rephotographs images from the television, or captures images from YouTube and other sources. These are just a starting point; Tuymans is no photorealist. Instead, his art is founded on a mistrust of all images, whether painted or photographed.

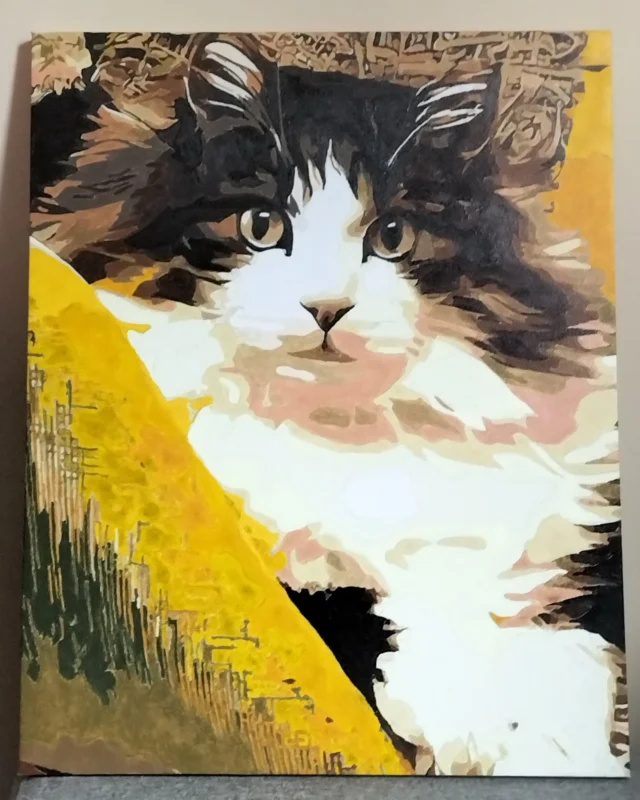

That he reused Van Giel’s photograph of a rightwing Belgian politician, taken in 2010, is not in doubt. Tuymans’s painting is both a portrait of a politician, and a painting of Van Giel’s photograph. Yet there is an enormous difference between the photograph and the painting. Scale is different. Colour is different. Shadows and highlights are shifted, recast, added to and emphasised, abbreviated and deleted.

Most of all, surface is different. The painting A Belgian Politician is not a reproduction. Comparing Van Giel’s photograph and a reproduction of Tuymans’ painting levels out the conspicuous fact that paintings and photographs are different kinds of objects, that we read in different ways. Seeing them in a newspaper or online reduces both to the status of flat images. This trivialises the painter’s emphasis on touch, and the way a painting is made, as well as its appearance as a picture. Tuymans was painting the politician’s face, but he was just as much painting the way Dedecker was described in the photograph – including the way the politician’s head was cropped and sliced in the newspaper image.

This is more than a semantic runaround. The similarities are beyond dispute, but so, too, should be the differences. The photo just looks sweaty. In Tuymans’ painting, the gleam is pustular, and the light has no black backdrop glamour. The tonality is greyed, and the way the brushmarks interrogate the subject’s nose and ear is horribly intimate. Coming down to details, everything is different, including the image’s construction.

Tuymans’ defence against the photographers’ copyright (under EU law) is that his painting is a parody. The judge disagreed. Put bluntly, he didn’t think the painting was funny or macabre enough to warrant that defence. Perhaps he would have been swayed by a more exuberent expressionism or overt caricature. He could not see the differences.

A photograph is no less a mediated image than a painting. Tuymans’ approach to all images is corrosive and analytical. This portrait needs to be seen in the context of the painter’s work as a whole – not least in relation to his 2005 painting of Condoleezza Rice, entitled The Secretary of State.

A deadpan approach marks Tuymans’ paintings of even the most loaded subjects. Humour here is found in the way a portrait is couched in the language of painting, which he treats with scepticism. He treats photographs like pictorial evidence, then approaches them, and painting, with a kind of detached irony. A recent judgement of the European court of justice defines parody as follows: “The essential characteristics of parody are, first, to evoke an existing work while being noticeably different from it, and secondly, to constitute an exception of humour or mockery.” How can one prove or disprove a will to mock?

Tuymans says: “When an artwork is oversimplified to fit a particular framework (the mass media) the artwork suffers the very kind of populist ‘dumbing down’ that I have spent my entire career fighting. Through my artwork, curating and writing and in my dealings with the main cultural institutions of this country, I have consistently endeavoured to promote knowledge and expertise over ignorance. My present statement about this court case is no different.” His lawyers write in a press release: “How can an artist question the world with his art if he cannot use images from that world?”

As it stands, the judgement imposes a fine of €500,000 (£384,000) if Tuymans creates any more “reproductions” of Van Giel’s work or shows the original painting, which now belongs to an American collector. I don’t know if the judge has ever seen the original, or only a photograph. Tuymans is going to appeal.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.