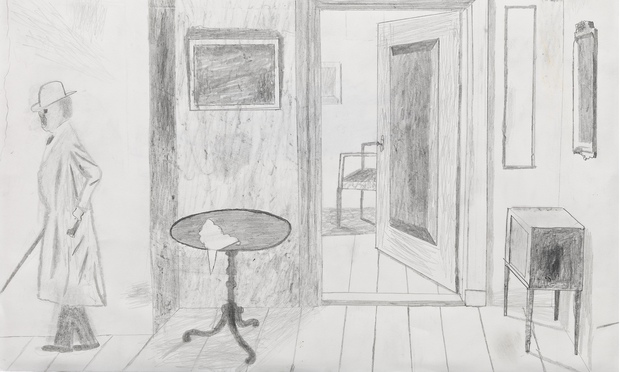

Ghost, 2014 (detail) by Jockum Nordström. Photograph: delfanne.com/© 2014 David Zwirner, New York/ London

The scene: the hall of a wood-floored house, somewhere in the past, with overtones of Strindberg or Ibsen. A handkerchief dangles wet and heavy from the edge of a table as if someone had drenched it with tears. The pictures on the walls are all blank, there is no obvious source of light and the empty mirror is sightless. A man in a topcoat with a cane is tapping his way down a corridor, stage left. Perhaps he too is blind.

Jockum Nordström’s Ghost is effortfully worked in pencil on paper. Here and there it resolves in tight geometrical perspective, as if made with heavy use of a ruler, but mostly it is juvenile, hesitant and awkward. If the scene is haunted, it is not so much by the man with the cane and the disproportionately tiny feet but by the sense of some strange child depicting his nightmares with a blunt pencil next morning. The work feels like an act of ventriloquism.

Nordström was born in Stockholm in 1963. He is one of Sweden’s most successful exports, a star in America since his 30s. His works are mainly paper-based – collages, watercolours, these bizarre, semi-sinister drawings – and their evident fragility is in direct opposition to their content.

Two women are going in opposite directions in another room. They might be mistress and maid, grown-up sisters, mother and daughter, who knows? Whatever the relationship, they are now utterly alienated. The smaller figure cannot reach the door handle, which appears to be missing in any case, and the larger figure is so entangled with her own clothing she could be wearing a straitjacket. It might be a child’s idea of adult life, or it might be a riddle expressed in a kind of stumbling vernacular. Who can say, when the action is stalled and the characters blocked?

The cast shifts. A pageant of medieval hounds chases across a collage only to encounter horned and devilish critters rearing up on their hind legs. In what might be a house, or a brothel, come to think of it, sex is going on in different rooms up and down the building and in many permutations across several centuries, as it seems, for the discarded garments include 19th-century frock coats as well as contemporary clothes. Nordström’s bestiary of monkeys, hares and horses intervenes, appearing both indoors and out, getting alarmingly in the way.

The collages are highly theatrical – the rooms like stage sets, one after the other on the same page, often in a nearly unfathomable narrative sequence – but the denouement is always thwarted. The drawings are like stills, where the action is suspended. Nordström often produces hybrids, running three strips of drawings across a collage, horizontally, but also vertically, like comic strips turned upside down.

One of the strongest works here, a massive two metre collage filled with a wild assortment of children and schoolmarms plucked from different eras, flings all its scenes up in the air at once – overturned desks, irate teachers, children nipping away – so that the overall mood is anarchic. But each figure is laboriously scissored and coloured in as if by one of the school children themselves, diligently doing her art homework. The effect is eerily dissonant.

Nordström makes great use of sugar paper, with its mute hues and pulpy texture. A whole Swedish landscape is implied with an overcast expanse of soft grey ovals and faded strips of foliage green. It’s not hard to imagine him working away in solitude in his farmhouse on the island of Gotland, weather and darkness pressing in around him. One of his drawings shows two men in antique clothes holding some kind of unintelligible conversation halfway up (or down) a staircase. They look unnervingly similar. The picture is called When I met myself.

Occasionally, the work becomes irksomely incomprehensible: where is the umbrella in Chapeau et Parapluie? What is the relationship between the lone black figure on one side of a diptych and the massive crowd on the other? And it’s hard to love his vignettes of half-dressed girls which, lacking any context, just look like willfully bad pastiches of outsider art. But at his best, Nordström seems to have tapped into the children of the past – or perhaps the child he once was – to create this world of curious disquiet.

Nordström’s work is in public museums all over the world, but not here. We stint on contemporary Nordic art (as opposed to literature and television) in Britain. Of course it’s possible to think of great exceptions over the years – Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s exquisite show of Finnish films at Tate Modern; the visual poetry of Iceland’s Hreinn Fridfinnsson at the Serpentine Gallery; the much-loved installations of Olafur Eliasson, still most famous for his radiant Turbine Hall sun. But what’s needed is a grand pan-Nordic gathering – and it would have to be big, there are so many candidates, not least the marvellous Swedish painter Mamma Andersson, Nordström’s partner – what a party that would be.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.