As Art Basel Miami Beach gets ready to open The Guardian takes a look at how the annual fair has completely transformed the region.

The tents are up and the taste-maker parties are under way. It’s the start of the trade-show-meets-tropical-bacchanal that is Art Basel Miami Beach. On the way into Miami, a taxi driver tells me the fair, now 12 years old, is bigger than the boat show and spring break.

From today, private jets will nose towards Florida delivering the super-wealthy into the waiting arms of art dealers and advisers, purveyors of lifestyle and luxury, and property developers. Some 267 galleries will descend with dozens more at eight satellite fairs. The city’s 70,000 visitors can expect art happenings such as a video showing Lady Gaga posing as the figure in Jacques-Louis David’s 1793 painting The Death of Marat; and an exhibition dedicated to André 3000, of hip-hop duo Outkast (in particular, the 47 slogan jumpsuits he wore on the band’s 20th-anniversary world tour this year.)

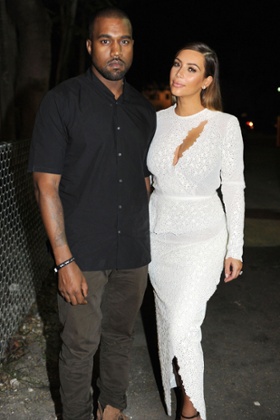

There will be a party hosted by David Lynch’s Parisian night-time hotspot Silencio, FKA twigs will be playing, and Solange has curated a stage. Kim Kardashian and Kanye West will be drinking Dom Pérignon poured from Iris van Herpen-designed bottles at a party called Wall, where guests have to go through three checkpoints to get in.

From the VIP openings tonight to the last gasp on Sunday, Art Basel Miami is a synchronisation of art and wealth. Few understand this better than Craig Robins. His offices are lined with art – John Baldessari, Richard Tuttle, Kai Althoff – and overlook the Design District, a former warehouse area just over the causeway from the beach. Robins helped bring Art Basel to Miami, a first step in the expansion of the respected Swiss art institution, and his company Dacra is behind the transformation of the district. New restaurants have sprung up. A new museum, the Institute of Contemporary Art, opens this week. The Bass Museum of Art will display the collection of Peter Marino, shop designer for luxury giant LVMH. The French company also happens to be a partner in Dacra: LVMH brands Céline and Louis Vuitton just opened stores down the street.

A decade of hosting parties and cultural events is paying off, Robins says. The neighbourhood has been remade. This is much more than a “sexy, fun in the sun, superficial place to party” – it’s now a brand. “The idea that a city can market itself around culture was launched in Miami. We’ve tried to integrate the art side into the business side, and success there gave us capital to do more culturally.”

Nowhere is the commercialisation of culture better demonstrated than on Miami Beach itself. Twenty years since the regeneration of the art deco district, Ukrainian billionaire Len Blavatnik is bankrolling Faena Miami Beach, the brainchild of Alan Faena, an Argentinian developer who successfully art-branded a rundown section of Buenos Aires. Faena has seven buildings under construction, including an arts centre, a luxury hotel and burlesque theatre designed by film director Baz Luhrmann to invoke the spirit of a Latino Great Gatsby. One reported buyer for Faena’s beachfront apartment tower is super-dealer Larry Gagosian. Dressed in white, from his Panama hat to his espadrilles, Faena says his project is not about developing a single hotel or building. “It’s about developing something game-changing for the city as a whole.” His brand co-ordinator Pablo De Ritis explains that the plan is to make a kind of “cultural Disneyland”.

“Everyone asks: how has art changed Miami?” says Florida art historian Bonnie Clearwater. “But the question is: how did Miami change art?” The city’s easy embrace of the fair, she says, set the stage for art to become more fun, more welcoming. Gallery owner and art lecturer Fred Snitzer says it’s been “profoundly positive” for his students, who get to see art they might not otherwise see.

Art fairs may be unseemly for many reasons: dealers say they’re almost entirely dependent on them for new business, and artists grumble they’re asked to make pieces to suit the fair schedule. The partying jetsetters seem the least of anyone’s concerns. “Miami is a magnet for slick, sleazy stuff,” Snitzer say. “It’s what we know.” He thinks it better to be exposed to the reality of the market than live in an insulated fantasy. “Artists can’t afford to be naive. If a serious artist is negatively impacted by luxury or money, then they weren’t very good in the first place.”

For Robins and others, bringing art to the city appears to have paid off. It’s got its own name: the Miami Effect. The city is going through a construction boom. There’s a feeling that the influx of wealth will support the development of an indigenous art scene, rather than have one imported for a week every December.

That’s certainly collector Mera Rubell’s hope. This year, on their 50th wedding anniversary, she and husband Don are showing highlights from their collection, including Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince and Charles Ray. Founding pillars of Miami’s art establishment, the Rubells moved to the city in the early 1990s. When they first suggested bringing Art Basel to Miami, the mayor imagined a flea market. So the Rubells flew him to Switzerland. “Money, visibility – he saw what a huge scene it was. You have to remember that art is now global and art fairs are the only way to connect.”

Rubell and John Baldessari sometimes talk about the time when there was no money in art. “It’s interesting,” she says, “that all these brands can’t live without artists. Their marketing depends on creativity and they need artists to define them.”

The Rubells have just purchased the Lord Baltimore, a lavish hotel in Baltimore within striking distance of the city’s incredible art trove that includes, Rubell says, around 700 Matisses. The next art destination? Sure. Why not? There always a new frontier.

• Art Basel Miami Beach runs from 4-7 December

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.