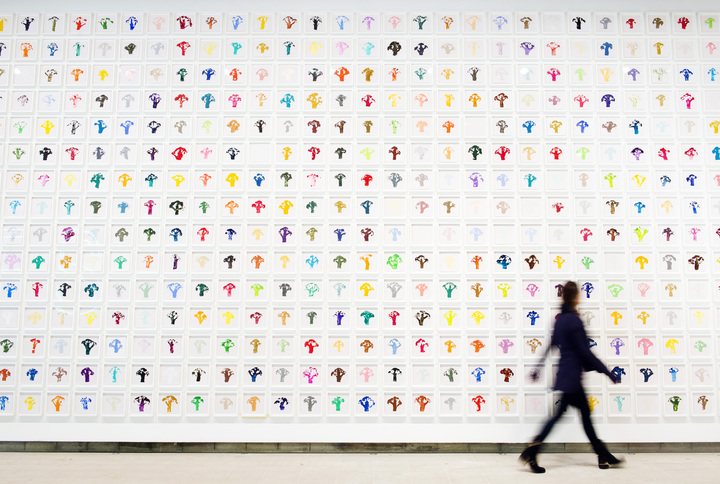

Work no. 1092,2011, Martin Creed, What’s the Point of it, Hayward Gallery, 2014 Installation view, photo Linda Nylind

What is this operative and seemingly elusive ‘it’ I ask British artist Martin Creed whose exhibition ‘What’s the point of it?’ has recently opened at the Hayward Gallery, “[the] it refers to everything,” Creed responds with bonhomie. “The exhibition title is a question I often ask myself, I don’t know [the answer] but it’s a good question.” So does the question refer to your professional life or your personal life, I enquire. “I don’t distinguish between my work and the rest of my life so it’s a question that refers to everything, he adds.” And a visceral everything is what Creed’s universe delivers.

‘What’s The Point Of It?’ is the most comprehensive exhibition to date of Creed’s oeuvre. It comprises of 160 pieces that straddle many genres and span a variety of scales in a gamut of mediums. Found objects, wall-mounted neon signs, film, photography, painted canvases, kinetic installations, sound work and extravagant sculptures all feature. It’s a multi-layered, multi-sensory compendium of ideas and gestures that prompt tacit questions about the commonplace and its role in everyday life, both its uniformity and its uncertainty.

Creed’s work strips away complexity and unpicks at any superfluity, even the sequentially numbered works are assigned with straightforward titles that negate fuss. Although his work is minimalist in approach honoring existing materials, informal objects and pedestrian situations, his output, as the exhibition testifies, is maximal.

Work no. 1000 ,2009-2010Martin Creed, What’s the Point of it, Hayward Gallery, 2014 Installation view, photo Linda Nylind

The exhibition presents Creed’s diverse body of work from his earliest works (many previously unseen in the UK) including a self-portrait painted at age 16, through to the latest version of his 2001 Turner-prize winning installation Work No. 227 The lights going on and off (2000) that simply comprised of a large, empty room in which the lights switched on and off at five second intervals. The press attention and controversy Work No. 227 garnered propelled its now-iconic status and established Creed as an internationally acclaimed artist. The exhibition also introduces Creed’s latest pieces including Work No. 1686 (2013), a stationary Ford Focus car that unexpectedly and periodically comes alive. Its engine erupts, the doors swing open, the bonnet lifts, the wipers start to wave, the radio switches on and the horn beeps loudly and then suddenly the car returns to its inanimate state only for the cycle to repeat itself. Located on one of the Hayward’s sculpture terraces, the backdrop of the Southbank,’s concrete vista lends itself well for Creed’s outside installation work: “I feel a bit uneasy if it’s a closed-off inward-looking place. I try to do my work outside as well,” he recently told a journalist. Incidentally, Work No. 1686 is one of Creed’s current favourite pieces: “It’s a new thing, I like it, it makes me laugh,” he told me.

Martin Creed, What’s the Point of it, Hayward Gallery, 2014 Installation view, photo Linda Nylind

The exhibition begins and ends with a battered leather sofa impeding access into the exhibition’s entrance, which also functions as the exit. Dominating the space is a colossal revolving steel construction that spells out MOTHERS in six foot high, white neon letters, as is the case of Creed’s other neon installations the choice of words likewise serve as the artwork’s title, Work No. 1357 MOTHERS (2011). Supported on a heavyweight iron beam the sign pivots at speed, with its arms cantilevered at such length yet moderate in height the structure narrowly escapes contact with the wall as well as visitors’ heads.

On the final floor is one of Creed’s best-known works, Work No. 200 Half the air in a given space (1998), a room densely filled with approximately 7,000 white balloons which individuals are invited to negotiate. Facing the ballooned enclosure are a pair of black curtains that mechanically open and close revealing an incongruous monolith set against London’s historic skyline, Work No. 990 A curtain opening and closing (2009). The juxtaposition between these two pieces suggests a playful dialogue.

Work No. 916, 2008, Martin Creed, What’s the Point of it, Hayward Gallery, 2014 Installation view, photo Linda Nylind

Between the ground and top floors is a miscellany of artworks. Work No. 79 Some Blu-Tack kneaded, rolled into a ball, and depressed against a wall (1993) and Work No. 88 A sheet of A4 paper crumpled into a ball (1995) are self-explained by their titles. Innocuous items such as chairs, tables, wooden planks and cardboard boxes are either stacked in order of size or arranged in sequences, often creating a pyramidal effect. A lineup of cactuses hierarchical in height appear tactile yet menacing, Work No. 960 (2008). Neon messages include Work No. 232 the whole world + the work = the whole world (2000) illuminated in white and Work No. 220 DON’T WORRY (2000) illuminated in yellow function as lyrical beacons at select moments.

Large-scale paintings, paintings made with eyes closed and another hung so high apparently Creed had to jump every time he wanted to add a brushstroke (it is also exhibited beyond the customary eye line thus requiring the spectator to jump for a proper viewing) all share the same visual rhetoric. Rollered-on stripes of colour fill the totality of an expanse of wall and crisscrossing stripes which can never be seen in their entirety adorn another. At mezzanine level are 1,000 prints made from broccoli heads inked onto the wall in assorted colours and finishes, Work No. 1000 (2009-10). Four images each of a person smiling are one of many photographic pieces and the short films screen visual absurdities such as the prosaic act of the artist shooing dogs and the bodily acts of vomiting and defecating.

Work No. 396, 2005, Martin Creed, What’s the Point of it, Hayward Gallery, 2014 Installation view, photo Linda Nylind

The exhibition is accompanied by a variety of sounds, unsurprising given that Creed is also a musician. The first gallery space is home to thirty-nine metronomes oscillating at different speeds, marking time at disparate tempos and thereby creating a cacophony of rhythmic beats. As you enter the adjacent gallery space an unassuming man sits at an upright piano playing the chromatic scale one staccato note at a time. Elsewhere a tittering laugh resonates through some hidden speakers and Work No. 1197 All the Bells in a Country Rung as Quickly and Loudly as Possible for Three Minutes (2012) which was commissioned to coincide with the 2012 Summer Olympics opening ceremony reverberates.

For Creed making music and making art are as important. He has collaborated with record labels Moshi Moshi Records and The Vinyl Factory, and in 2011 he launched his own label, Telephone Records. Fans can sample Creed’s musical compositions on 8th February at the Royal Festival Hall where his band will perform tracks from his newly released album Mind Trap.

Work No. 998, 2009, Martin Creed, What’s the Point of it, Hayward Gallery, 2014 Installation view, photo Linda Nylind (15)

As individual pieces some works engaged while others triggered indifference, however en masse the exhibition left me in a state of delirium. Creed was once asked what thematic framework he would characterise his artistic practice to which he replied Expressionism: “Everything that everyone does is always an expression.” Later in the day and once again confronted by the show’s title, a Jean-Paul Sartre quote from his 1957 tome Existentialism and Human Emotions came to mind, “Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself.” I thought this applicable.

Martin Creed, What’s the Point of it, Hayward Gallery, 2014 Installation view, photo Linda Nylind

Martin Creed: What’s the point of it? 29th January – 27th April 2014?

Hayward Gallery, Southbank Centre, Belvedere Road, London, SE1 8XX www.southbankcentre.co.uk

Words: Stephanie Talbot