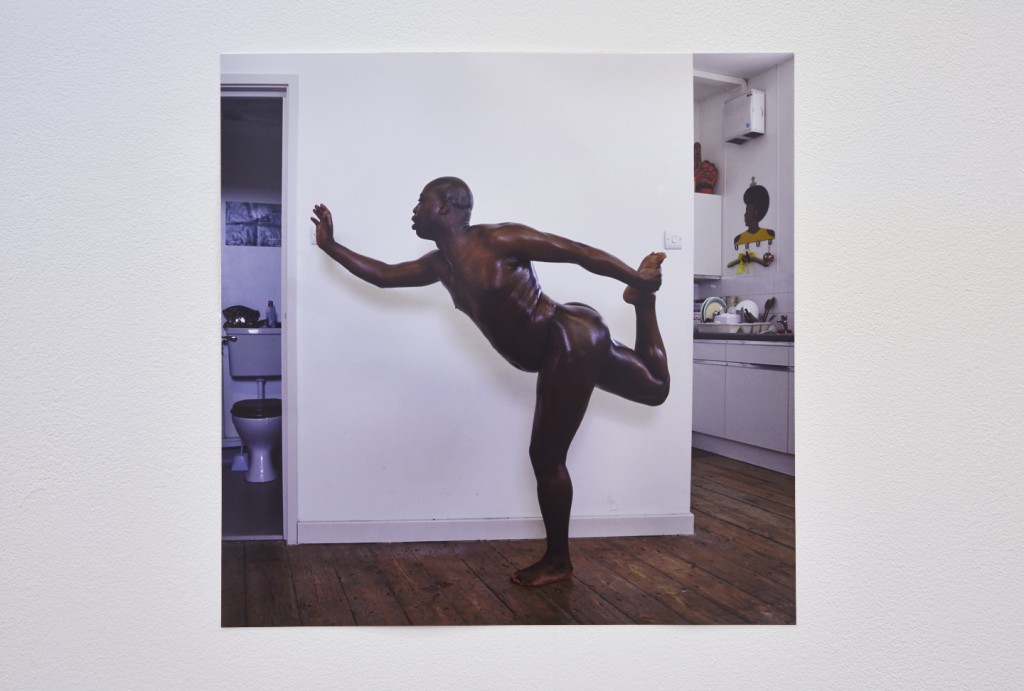

Harold Offeh, ‘Covers: After the Rolling Stones, Exile on Main Street, 1972 (3 Balls) 2013’, 2013, C-print. Courtesy the artist.

Harold Offeh, ‘Covers: After the Rolling Stones, Exile on Main Street, 1972 (3 Balls) 2013’, 2013, C-print. Courtesy the artist.

Harold Offeh is currently exhibiting on Biopic, a group show curated by Nathan Jenkins, and also including Gabriel Acevedo Velarde, Miguel Aguirre and Philip Newcombe. Biopic runs through to 21 December 2013. Maria Stenfors, Unit 10, 21 Wren Street, WC1 OHF. Opening hours: Tues- Fri (11am-6pm). Sat (11am-3pm) www.mariastenfors.com.

Selections from Offeh’s ‘Covers’ are also included on the group exhibition ‘The Shadows Took Shape’ at the Studio Museum, Harlem, New York. ‘The Shadows took Shape’ closes 9 March. Studio Museum, 144 West 125th Street, New York, New York 10027 www.studiomuseum.org

For his first curated show ‘Biopic’, at Maria Stenfors, Nathan Jenkins selected work from Offeh’s ‘Covers’ series. ‘Covers’ is an ongoing project in which Offeh explores music album covers from the ’70s & ’80s, re-imagining their images (and the music they represent) as performances which are developed through photographs, video and live performance. As part of Biopic’s exhibition programme, Offeh performed ‘Covers: Playlist’, at Maria Stenfors, staging a series of performances in dialogue with actual covers and specific tracks, selected off the albums.

Interview by Yvette Greslé

What are the ideas driving the work shown here at Maria Stenfors?

The work shown here on ‘Biopic’ comes from a series I’m busy with called ‘Covers’. It explores album covers from a period of time – the ’70s and ’80s. Some images I’m really familiar with through family histories and music collections. I was born in the ‘70s and it encapsulates a moment for me. I think a lot about identity and about what was happening culturally post ‘60s.

I’m really interested in thinking about manifestations of visual culture. Album covers are, in a sense, illustrations of music; and the image has a really interesting relationship to audio and to text. What I found with a lot of them, particularly funk, and soul, is that you get a real articulation of black identity. A space was opened up by ‘60s culture and civil rights movements, colonial emancipation and Black Consciousness. People were saying we’re not going to be framed by old ways of seeing (and thinking about how they want to represent themselves). About what identities they were going to embrace and formulate. I think the album covers and the artists were really playing with all this. They represent, for me, a really interesting visual culture, and a reference point.

I like that album covers have a function and that the images are in service to something. That’s really interesting to me. They’re articulating something about the artist’s identity or a thematic strand within music or musical genre. I explore the covers through photography, video and live performance. I’m thinking about these different modes and how the audience engages either through the medium or through an encounter. With the ‘Covers’ series I’m using a performance trope which is duration, trying to interrogate the still image and the live image, and the gap between the two.

You were born in 1977, and you’re looking back in these works at the decades of your birth and your childhood. What is interesting for you about this and about being an artist now, in the twenty-first century?

One of the most difficult things is trying to make sense of the contemporary because of being so immersed in it. What becomes very useful for me is to reflect on the past and to visit it through things like cultural images and music. It’s not just about a pastiche or parody. In a way it’s trying to make sense of the past in relation to the now. I’m interested in making sense of what it means to have a multifaceted identity. What does it mean to be invested in different cultures and have various allegiances? My work is not necessarily about nostalgia. I don’t actively have memories of the ‘70s but it’s that sense of trying to reconnect and engage with the past.

A lot of the politics from the ‘60s and ‘70s was really didactic. I like that it was really positioned. It’s quite liberating. We come out of a moment in the past decade where I think people haven’t really had strong positions, politically. I think sometimes having a position can stimulate more debate.

Harold Offeh, ‘Covers: After Grace Jones, Island Life, 1985 (Graceful Arabesque) 2008’, 2008, C-print. Courtesy the artist.

Harold Offeh, ‘Covers: After Grace Jones, Island Life, 1985 (Graceful Arabesque) 2008’, 2008, C-print. Courtesy the artist.

Myth is something you think about a lot in your work.

I’m really interested in this idea of myth creation. There’s a fantastic quotation from the avant-garde musician Sun Ra who in the ‘70s wrote and performed in the science fiction film ‘Space is the Place’. He talked about the black experience as being ‘We are Myths’. I think there are really interesting examples of people creating their own myth narratives. Grace Jones is an example. I’ve recreated her album cover for ‘Island Life’ where she performs this statuesque, arabesque pose. She’s formulating a very positioned identity – an androgynous, Amazonian figure. But in its construction the image is also a fallacy: it is actually a composite. It’s really impossible to fully embody. My strategy with a lot of the ‘Covers’ series is to interrogate the mythology of the image through a kind of embodied experience of them. I use performance as a strategy to explore images.

You deliberately performed the Grace Jones ‘Island Life’ cover in a banal, domestic context; and this performance is documented in a video, and in a photograph.

Yes. I was interested in the dislocation between the aspiration of the image and its reality. I was exploring what would happen if I embodied it. Often myth narratives are really exaggerated. I was trying to find the mechanisms and devices that were used in the construction of the image.

What was interesting for you about the Rolling Stones cover, ‘Exile on Main Street’? You focused in on one particular image, the guy with the three balls in his mouth.

I was really drawn to this image, which is such a small part of the album cover. He interested me partly because of his story. He’s an actual person called ‘Three Ball Willy’. He was a sideshow, circus guy: In the ‘20s and ‘30s he was known for being able to get a tennis ball, a golf ball and a baseball into his mouth. I was thinking about what it means to objectify oneself in a very particular way. In the past I’ve looked at the history of black and white minstrel shows. I’m really interested in self-parody. A lot of the early black minstrels, who were black, put on blackface. It’s really amazing that they were prepared to embrace this stereotype. Often where identities around race, gender or sexuality are concerned there’s an embrace of an oppressive stereotype. It can either be a political challenge or strategy.

Works from the ‘Covers’ series are included in the exhibition ‘The Shadows Took Shape’ at the Studio Museum Harlem (New York). The show thinks about Afrofuturism. What’s interesting for you about Afrofuturism? It’s getting a lot of attention at the moment.

I’m interested in the possibilities that are presented by sci-fi. It’s never really about the future. It’s always about the contemporary. Sci-fi becomes a conduit that allows people to really explore the present. In formulating a future, sci-fi has to draw on the contemporary. If you look back at earlier sci-fi (at past futures) you get this really fascinating insight into the ‘30s, ‘60s or ‘70s. The idea of formulating a future feels quite emancipatory because it’s like ‘I can just make it up. It’s my vision. It’s my world’. It allows you to explore things about the present that are quite difficult to articulate.

Harold Offeh, ‘Covers. After Betty Davis. They Say I’m Different, 1974’, C-print. Courtesy the artist.

Harold Offeh, ‘Covers. After Betty Davis. They Say I’m Different, 1974’, C-print. Courtesy the artist.

What do you think Afrofuturism has to contribute to discussions about race?

I think there’s a moment in the ‘60s around Cold War Politics and the Space Program where this notion of man on the moon coincides with civil rights movements. I think there is a cross-fertilisation: a new colonial mode where we’re now exploring space. But actually this doesn’t have to be inscribed with the same politics that we’re dealing with on terra firma. I think a lot of artists and thinkers really embraced the moment that opened up in the 1960s. A lot of people of my generation, and younger, have returned to the ‘60s and are interested in a whole history that hasn’t really been dealt with, archived or critically evaluated. There’s now an excavation of these hidden narratives. Sun-Ra is formulating this identity in the ‘50s and ‘60s but everyone knows about David Bowie and Ziggy Stardust.

Tell us a bit more about the work on the show in New York – ‘The Shadows Took Shape’.

I’m showing three photographs. There’s the Grace Jones piece. A work based on an album cover from George Clinton’s ‘Funkadelic. Maggot brain’ (1971). The original cover is of a woman buried in soil except for her head. She looks like she’s screaming and you’re not quite sure if the scream is about agony or ecstasy or both. There’s another image which is based on a little known funk artist called Betty Davis (she was married for a short time to Miles Davis). She’s wearing this Space costume and is holding this really interesting, kneeling-crouching pose. There’s a kind of sexual posturing that happens in a lot of these images. I’m really conscious about their articulation of women, and how each woman is represented.

Where do you see yourself as an artist now?

I’ve recently come back from the Performa Biennial in New York and am thinking a lot about performance. One of the things I’m constantly drawn to in performance is the idea that it is an activity, it’s a verb. I find that really liberating in terms of possibilities. I pay attention to how the gesture of the artist manifests itself through performance. That’s when performance becomes really exciting and open.

Harold Offeh. ‘Covers. After Funkadelic. Maggot Brain, 1971 (V2)’, 2013, C-Print. Courtesy the artist.

Harold Offeh. ‘Covers. After Funkadelic. Maggot Brain, 1971 (V2)’, 2013, C-Print. Courtesy the artist.

‘Biopic’ at Maria Stenfors runs through to 21 December 2013 www.mariastenfors.com

For more about ‘The Shadows Took Shape’ at the Studio Museum, Harlem, Ne w York www.studiomuseum.org

See also the artist’s website www.haroldoffeh.com