Kimathi Donkor: ‘Daddy, I want to be a black artist’ @ Peckham Space- Kimathi Donkor (b.1965) is one of the most significant figurative painters, of his generation, working in the United Kingdom today. London-based, his recent exhibitions include ‘Queens of the Undead’ (Iniva, London, 2012), and the 29th São Paulo Biennial (Brazil, 2010). Donkor who is a graduate of Goldsmiths College and Camberwell College of Arts, has been the recipient of Awards, Residencies and Commissions including the 2011 Derek Hill Painting Scholarship for the British School at Rome. He is currently a practice-led Ph.D candidate at Chelsea College of Art and Design.

Donkor’s paintings bring a visual language of closely observed human figures into a dialogue with History, both as art and as narrative. Historical events and accounts bound up in questions of race, colonialism, slavery and contemporary forms of violence are powerful, urgent themes. His paintings are distinctive in their dialogue with the history of colour, perspective and the imagining of human figures in grounds that oscillate between illusion and the canvas, as a flat, two-dimensional surface.

Donkor’s current exhibition ‘Daddy, I want to be a black artist’, at Peckham Space, presents two new paintings: ‘Oshun visits Gaba at Tate’s “Big House”’ and ‘London visitation from Nanny of the Maroons’. These large-scale works are extraordinarily beautiful explorations of intense, luminous colour and human figures in relation to heritage, architecture, and space (both public and private).

Directed by Emily Druiff, Peckham space, together with partners and critical friends, is committed to working closely with young people and residents of Peckham, to encourage positive creative experiences. The exhibition with Kimathi Donkor is in collaboration with Leaders of Tomorrow (LOT), a leadership, enrichment and development programme designed to raise the academic achievements of young people, particularly those of Caribbean and African heritage. LOT (London) was established by Vallin Miller in 2002, and is a partner of Peckham Space. More about Leaders of Tomorrow can be found at www.lotlondon.org.uk.

‘Daddy, I want to be a black artist’ runs through to 24 November 2013, Peckham Space, 89 Peckham High Street, SE15. The gallery is open Wed–Fri, 11am–6pm and Sat–Sun 11am–5pm. See the website for more information and associated events www.peckhamspace.com.

Interview by Yvette Greslé

Tell me about your collaboration with Peckham Art Space which included mentoring a group of young people from Leaders of Tomorrow (LOT). This process and the dialogue that developed between you as an artist, and the group of young teenagers, informed the making of two new paintings.

Peckham Space approached me about working with Leaders of Tomorrow. The idea is to introduce school children/teenagers to aspirational figures in black leadership, not only in Britain but around the world. This prompted me to think about black leadership in Britain. There are several black artists who represent artistic excellence and have received recognition. But at the same time, this recognition can be quite art-world, and is not necessarily more widespread. I thought it would be interesting to take these young people to Tate Britain and introduce them to examples of high profile black British artists (examples of black leadership within my field, contemporary art). Tate is also the subject of my PhD thesis. We went behind the scenes at Tate. Our first encounter was with the Conservation team who showed us a piece by Donald Rodney, who I knew (he died in 1998). He was quite a young artist whose interests were very radical and political. What struck me then, and in subsequent encounters at Tate Britain and then Tate Modern, was this group of young people’s enormous enthusiasm, optimism, and determination to succeed. Leaders of Tomorrow normally meet at gallery closing times and so we had to get special access to Tate. We would wander around the galleries after hours. What struck me was the way they’d stop and want to talk about work that grabbed their attention, and not just the pieces that I had decided to focus on (Chris Ofili, Donald Rodney, Frank Bowling and so on). They were really into it. I was struck by their enthusiasm, and it got me thinking about the whole notion of studiousness, enthusiasm, love of knowledge, love of culture.  Kimathi Donkor and one of the Leaders of Tomorrow with ‘Oshun visits Gaba at Tate’s “Big House”‘, oil on canvas, 2013. Courtesy of the artist. Kimathi Donkor: ‘Daddy, I want to be a black artist’ @ Peckham Space

Kimathi Donkor and one of the Leaders of Tomorrow with ‘Oshun visits Gaba at Tate’s “Big House”‘, oil on canvas, 2013. Courtesy of the artist. Kimathi Donkor: ‘Daddy, I want to be a black artist’ @ Peckham Space

The painting ‘Oshun visits Gaba at Tate’s “Big House”’ is based on a visit to the Meschac Gaba show at Tate Modern, his Museum of Contemporary African Art.

Gaba’s exhibition included a series of dinner events in collaboration with artists. We were invited to a special artist dinner by Harold Offeh. He invited guests to create a collaborative artwork together in the form of a ‘gathering’ that encouraged a form of dialogue and exchange via a series of calls and responses. There was a very participatory element to the whole of Meschac Gaba’s exhibition. One of the rooms of his Museum of African Contemporary Art is a Salon, where there was a baby grand piano. On the evening of the dinner, I heard some really nice jazz music coming from that part of the Museum. One of the Leaders of Tomorrow, one of the young teens, was sitting there playing, and doing some really beautiful improvisatory work. People started gathering around and began singing. It was amazing. All of this made me think about creativity, studiousness and inspiration in general – this was the wellspring of the two paintings I then made. I also introduced some of my own concerns into the work. These include the flying figures, named in the titles. The figure Oshun is a Yoruba goddess of creativity, fertility, beauty. The figure in ‘London visitation from Nanny of the Maroons’ is a national heroine from the colonial era. These figures are like angelic guides. In ‘Oshun visits Gaba …’ the setting is one of Tate Modern’s galleries looking out over the Thames. You can see St Paul’s in the distance. In ‘London visitation …’there is a more domestic space looking out over a typical South London back garden, with Victorian buildings and beautiful summer trees.

I am struck by colour in both the paintings, so intense and luminous. You appear to have a particular interest in colour.

Yes, as a painter that’s your first interest even before drawing, in a sense. With drawing you have line but with paint you have colour. So for many years I’ve been working on ways to integrate really intense and very striking areas of colour. But in a way that presents an abstract element or feel to the work while at the same time conveying a sense of naturalism. I work in a way that is very reminiscent of Renaissance Italian or Dutch painting which works with illusionism, single-point perspective and very well delineated figures. It’s a way of painting that draws you into an illusion. One of the ways I use colour is perhaps as a barrier to that, it stops and reminds you that this is a painting. It’s been constructed and it’s an artificial thing. It’s perhaps a way of allowing a person to appreciate the beauty of the painting.  Kimathi Donkor and one of the Leaders of Tomorrow with ‘London visitation from Nanny of the Maroons’, oil on canvas, 2013. Courtesy of the artist. Kimathi Donkor: ‘Daddy, I want to be a black artist’ @ Peckham Space

Kimathi Donkor and one of the Leaders of Tomorrow with ‘London visitation from Nanny of the Maroons’, oil on canvas, 2013. Courtesy of the artist. Kimathi Donkor: ‘Daddy, I want to be a black artist’ @ Peckham Space

You also seem to work with symbolism a great deal. The figure of Oshun holds a bell, and the ‘Nanny of the maroon’s’, holds a horn.

Some of the Leaders of Tomorrow have Nigerian heritage. This actually came out on the night of the dinner with Harold Offeh at Tate Modern. We were asked to participate in an improvised calling response, by Offeh, and one of the Nigerian teens used a Yoruba greeting. I thought about Oshun as a figure and the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove in Nigeria where her main shrine is. There is a yearly festival and as part of the ceremonies people ring little brass bells, and click their fingers over their heads to ward off evil spirits and bring good luck. The Orisha religion in Yorubaland is still strong and spread through colonialism and slavery. It’s now present across the Americas (Brazil, Haiti, Cuba) – these regions owe their ideas about spirituality to this Yoruba tradition. This is what I’ve tried to embody here.

You’ve paid close attention in these works to the human figure, gestures, facial expressions and so on.

Figurative painters are incredibly sensitive to all the minutiae of the human body – down to the tiniest detail to do with gesture, posture and facial expression. How does the direction of a figure’s gaze draw your eye to a particular section of the composition? All of this is important to the painting’s composition. In this sense, perhaps I am thinking about my own relationship to art and creativity. What are the things that draw my attention, as a figurative painter?

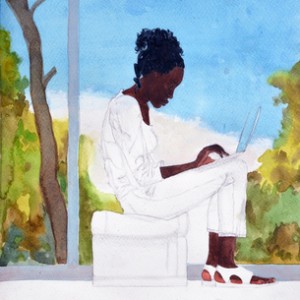

Do you always begin with watercolour and pencil when you’re thinking about new paintings? I’m interested in how some parts are left empty, while others are coloured in with the watercolour.

I do tend to do quite a lot of drawing. That’s how I begin thinking about my composition. In the first watercolour sketch I coloured in the whole of the surface. I really like a lot of Japanese and Chinese painting. One of the things in Ancient Japanese and Chinese painting is how so much of the composition is left unpainted. The focus is on certain elements and details – quite a contrast to European Renaissance painting, where my main focus has been and where you cover the entire surface and everything is colour.

Kimathi Donkor, Study for ‘London visitation from Nanny of the Maroons’, 2013. Courtesy of the artist. Kimathi Donkor: ‘Daddy, I want to be a black artist’ @ Peckham Space

What interests you so much about the figure of the girl on the laptop, which is repeated in the watercolour sketches, part of the preparatory work for ‘London visitation from Nanny of the Maroons’.

From talking to these teens and getting a sense of their interests and their attitude to life I got this very strong sense of studiousness and the desire to succeed. I’ve spent a lot of my life sitting around people who are studious, with their heads in a laptop. This figure could be interpreted in any way because you could be doing anything on a laptop. It is a machine which grabs our attention and we can pour out our interest and creativity in it. The watercolours were part of the process of thinking about iconographic elements, and gradually working them into the composition. I also feel that we are living in an age of increased female empowerment.

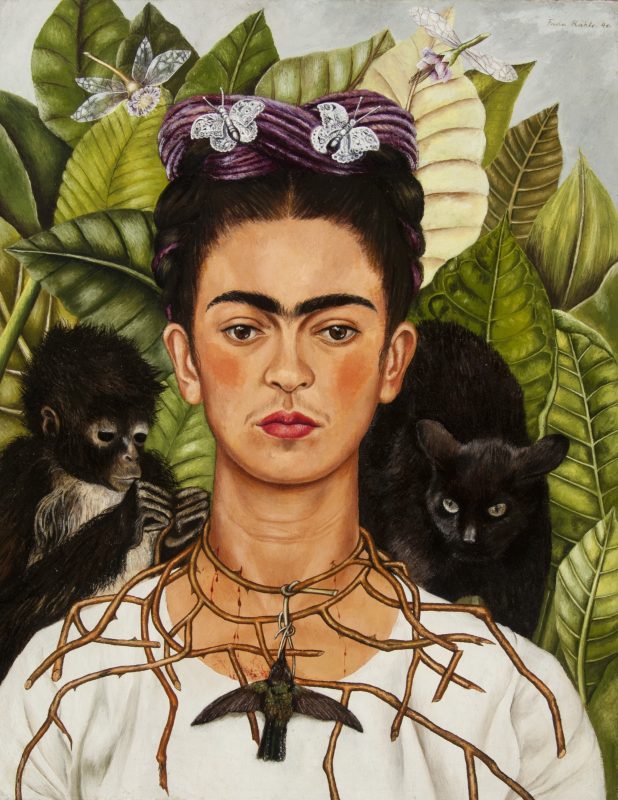

Kimathi Donkor, ‘Drama Queen’, 2010, oil on linen. Courtesy of the artist. Kimathi Donkor: ‘Daddy, I want to be a black artist’ @ Peckham Space

Kimathi Donkor, ‘Drama Queen’, 2010, oil on linen. Courtesy of the artist. Kimathi Donkor: ‘Daddy, I want to be a black artist’ @ Peckham Space

Your work as a whole seems to figure many strong female figures.

Absolutely. I’ve been working for many years on a series called ‘Queens of the Undead’, shown at Iniva in 2012. I refer to four ‘Queens of the Undead’: the 17th century Queen Nzinga of Angola; Nanny of the Maroons (born in Ghana she was a Jamaican slave who led a series of rebellions against slavery); Harriet Tubman (born into slavery, in America, she freed herself, and became a leading abolitionist) and Yaa Asantewaa (who led the Ashanti rebellion against British colonialism in Ghana in 1900). What unites these women is their African heritage and their military roles: they all broke the boundaries of female historical characters. They are similar to figures such as Joan of Arc or Boadicea. Many nations have these heroic female figures.

Where does the reference to Gaba’s ‘Big House’ come from?

That’s Tate’s Big House. It’s a reference to Henry Tate who was a sugar magnate. His fortune was built on sugar plantation slavery. If you read Gone with the Wind or Uncle Tom’s Cabin or any of the American slave era literature or folklore then often the plantation owners house would be called ‘The Big House’.

Your paintings think about history in a very interesting way. You make visible histories that are hidden to a Eurocentric way of seeing the world.

What interests me about these figures is that they are not that hidden. If you live in any of the countries where they come from, they are very well known. They are visible on bank notes, statues in squares. In some ways this speaks to how national cultures are insular. As much as we think we know about the rest of the world there is so much that we don’t have a clue about.

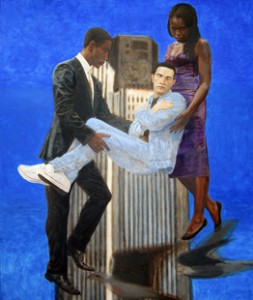

Kimathi Donkor, ‘Johnny was Borne Aloft by Joy and Stephen, 2010, oil on linen, 2010. Courtesy of the artist.

Kimathi Donkor, ‘Johnny was Borne Aloft by Joy and Stephen, 2010, oil on linen, 2010. Courtesy of the artist.

I see a relationship between your work and place, or geography. I was struck by the painting for the São Paulo Biennale, and how you engaged São Paulo but also London.

The building is Tower 42 which is the iconic City of London building. It’s symbolic of the apparent wealth of our glorious capital. The work was commissioned by the São Paulo Biennale Foundation. They proposed to me that I do a commission, or make a proposal to them about the death of Jean Charles de Menezes. He was a Brazilian who came to London from São Paulo and was shot to death by metropolitan police who mistook him for a suspected bomber. This was a few days after the 7 July 2005 London bombings. Jean Charles lived about 100 metres to the other side of the square where I live, in South London. I didn’t know him but he was a close neighbour of mine. His death had a strong impact on me personally. The police were looking for someone who looked more like me, the actual person they were hunting.

Kimathi Donkor, ‘Madonna Metropolitan’, oil on linen, 2005. Courtesy of the artist.

Kimathi Donkor, ‘Madonna Metropolitan’, oil on linen, 2005. Courtesy of the artist.

Probably to do with other work which I’d done in relation to policing in London, the Biennale asked me whether I’d like to do a painting that addresses this kind of thing. So I did this very Catholic image, perhaps related to Titian or Caravaggio, with these angelic figures bearing Jean Charles up through the atmosphere. They don’t have wings but you do get this sense of them floating. I wanted to do something that is sensitive to Jean Charles’ background, his country, Brazil is a very Catholic country. The other two figures are very symbolic of Stephen Lawrence and Joy Gardner who also had unfortunate encounters with the police. There is this pattern of these three figures who in one way or another came from migrant communities in London. All three had really violent deaths which exposed inequities in how the police have dealt with these communities.

I try to let my paintings speak. What the painting for the São Paulo Biennale tried to address is a sense of mourning but also a sense of hope and memory. If we do remember these things, and try to confront some of the issues they raise, hopefully this will lead us to a more tolerant and less aggressive city.

Installation view of ‘London visitation from Nanny of the Maroons’. Courtesy of the artist.

Installation view of ‘London visitation from Nanny of the Maroons’. Courtesy of the artist.

Was the title of the show (‘Daddy, I want to be a black artist’) your idea?

I wanted to choose a title that thought about the project, and the idea of introducing these young people to black artists. I wanted to talk about inspiration, desire, commitment, and the determination these young people have. I framed it as an imaginary conversation in which a young person is expressing what they want to do with their life.

Was there anything particularly special that you got out of this project and these paintings as an artist?

I think definitely in terms of the actual painting. What I’ve done with the areas of sky – these intense blues is something I’ve been working with for many years but I think I’ve made a further breakthrough aesthetically in the way that I’ve been able to use colour, landscape, composition to generate this mood of optimism. In a lot of my earlier work there was more menace or ambiguity.

The paintings do embody a sense of inspiration, the protective female figures, the luminous colours.

That’s what I wanted to get across, something that is quite optimistic and hopeful. Leaders of Tomorrow try to embody a communal sense of care for young people. We all know these stories about young people particularly in places like Peckham who are demonised as being out of control etc. But the other side of that is where society, and communities, try to guide and bring young people on, help them to find direction and go forward.

‘Daddy, I want to be a black artist closes 24 November, 2013.

For more about the show visit www.peckhamspace.com

For more about Kimathi Donkor see www.kimathidonkor.net