Sitting in a Berlin gallery over a cup of tea, Anish Kapoor is clearly at home in a city that is about to stage one of his largest ever shows.

The British-based artist says the exhibition, entitled Kapoor in Berlin, is the best show he has yet put on, which may have much to do with the fact that he feels Germany demonstrates a huge degree of respect for the arts – in stark contrast to Britain.

“Germans have a rather healthy respect for the arts and artists,” he said, in an exclusive interview with the Guardian, adding that that attitude could “not be more different” from the British perspective.

“In Germany, it seems that the intellectual and aesthetic life are to be celebrated and are seen as part of a real and good education, whereas in Britain, traditionally – certainly since the Enlightenment – we’ve been afraid of anything intellectual, aesthetic, visual.”

These perspectives were reflected in the two countries’ drastically differing policies on financial support of the arts, he said.

“In the UK, while the arts are the second biggest sector after banking, they probably form less than one tenth of 1% of government spending. It’s completely scuzzy. The UK has two things, the arts and education, and both of them it pushes into the corner. It’s the hugest, hugest mistake. Why do British ministers meet anyone from the arts other than to cut them? Compared to Germany, Britain has got quite a long way to go there, frankly

“In short, Britain’s fucked.”

One of the most highly regarded sculptors in the world, Kapoor is keeping much of the vast show, which covers more than 3,000 sq metres (0.7 acres) at the Martin-Gropius-Bau, under wraps. But he does reveal that around half the works were created especially for the show. It was, he explained, his concerted effort to stop it from becoming a retrospective, the idea of which he is keen to resist as long as he is alive and working.

“I don’t see the reason to be doing a retrospective,” he said. “Let somebody else do a retrospective for me. There doesn’t seem any reason to dwell on what’s been done. Rather, let’s build on it and try and do something else. I’m trying to push my practice out there and to see, ‘Can I do that? Will it go there?’

“A good half of the show is new, and that’s always a risk. But that’s the sort of idiot I am.”

Kapoor in Berlin is a culmination of the artist’s huge body of work of the past three decades, an extravaganza of colour, shapes and textures that its British curator, Norman Rosenthal, has called an “endlessly inventive theatre of sculpture”.

As Kapoor chatted, around him bustling workers in hard hats glided up and down on cranes, sprayed pigment on to walls, and removed plastic covers from sculptures as the show took shape.

Later, in a sneak preview, the Guardian was invited to see the works, including the centrepiece of the show.

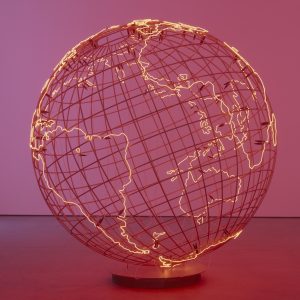

Emerging from holes in walls and a trapdoor in the floor, conveyor belts rise skywards, carrying big rectangular blocks of viscous, wine-red wax. As the wax moves up, it produces a squelching sound before falling off the end of the belt and landing with a satisfying splat on the linoleum floor. Overseen by a huge crimson sphere suspended from a metal frame, Symphony for a Beloved Sun is a new creation that fills the gallery’s main atrium.

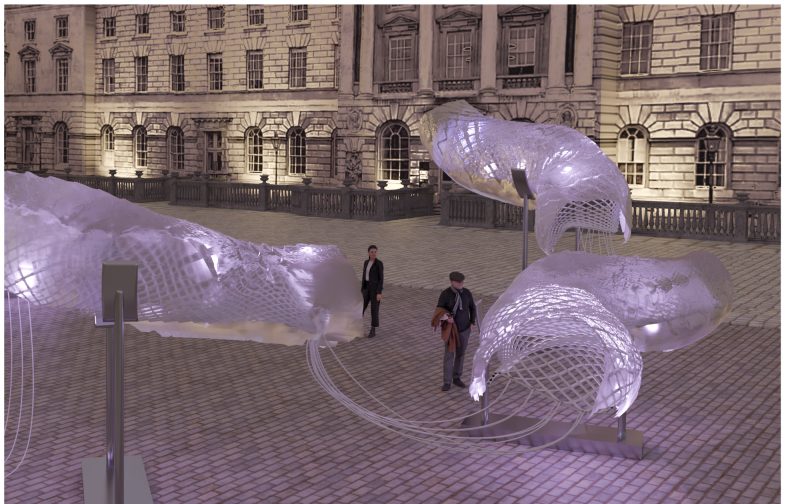

Along with the other structures, it reveals the potential the show has to beguile the public, something Kapoor’s audience has long come to expect of him. There is everything from a deflated whale, whose maroon mass spills across three rooms, to warty, cave-like innards fashioned from synthetic resin, huge geometrically fragmented mirrors, twisted stainless steel pillars and a gigantic, slowly rotating wax bell. There is even an old British Telecom generator.

Crafted from sandstone, alabaster, Kilkenny limestone and fibreglass are also the protuberances and orifices, mountains and tomb-like structures that have become Kapoor trademarks, including the subtle bulge in the wall called When I’m Pregnant, all of which reflect the long and complex history of Britain’s most celebrated sculptor in a show he said was “private and public in a very curious, sometimes uncomfortable mix”.

Exhibiting at the Martin-Gropius-Bau, a neo-renaissance pile in the centre of Berlin, was both a challenge and an inspiration for Kapoor, who had to deal not just with its complicated, decorative interior,of late-19th-century ornate pillars and mosaics but also with the history that envelops the building: the Berlin Wall and the SS headquarters are literally squeezed up against it, visible from the gallery’s windows; and he makes deliberate references to them in his works.

“It’s a building with a curious, difficult history that is inexorably linked to the history of Berlin,” he said. “That’s very potent. You can’t make a show here without some reference to all of that. And it certainly makes a show here so much more interesting.”

Symphony for a Beloved Sun is a nod to one of Kapoor’s heroes, the late German sculptor Joseph Beuys, who exhibited in the same atrium space shortly after the building’s postwar restoration, in 1982. It also strongly alludes to the industrialised, bloody mass murders of the Nazi era, according to Rosenthal. German critics have been quick to make the same connection to the favourite among Kapoor’s fan base, Shooting into the Corner – which has been given a room of its own – in which a cannon fires round pellets of wax into the far corner, staining the walls a blood red.

“We’re pleased to say the wax stains can be removed when smeared with margarine,” said the Martin-Gropius-Bau’s director, Gereon Sievernich, highlighting just one of the many challenges the 59-year old artist’s works have posed as he inspected a show that is still very much under construction five days ahead of its opening.

Other practical headaches have included the transportation, by a convoy of lorries, of the huge pieces from Kapoor’s Camberwell studio. Some had to be dismantled before they could be brought into the gallery; others were heaved in on horizontal cranes after window frames had been removed.

For Kapoor, the arrival of his works in the space for which they were conceived over a period of months, during which their creation dominated his life, brings with it a huge sense of achievement. “Getting things out of the studio is great, very exciting,” he said. “It’s only when they are in the real world that they have a life of their own.”

The Indian-born sculptor, who has had major shows at the Royal Academy in London and the Turbine Hall in recent years, said he had been attracted to Berlin in part by its strong artistic community, which includes major British artist friends of his such as Douglas Gordon and Tacita Dean; they, in turn, have been drawn here by the strong encouragement given to the arts. He also found enticing the feeling that “it has a sort of lifestyle apart – it’s a city of the alternative”.

“I expect today London is much more the centre of cultural activity than Berlin is,” he said. “And yet, there is the sense that what happens here matters. It has a very interesting relationship between the local and the international.”

One of his own favourites among the new works – which he described as a “mad, crazy idea – is the deflated PVC whale, called Death of a Leviathan. It takes up an entire side of the building, and reinforces Kapoor’s sense of responsibility towards tackling major societal issues.

“It’s a big deflated skin, like a huge dead whale, a Hobbesian reference to the state being a kind of Leviathan beast that gives its control to the individual,” he said. “Death of the Leviathan may imply the kind of death or deflation of the state, this present condition we seem to be in all over the world where the individual has to take responsibility for the things that the state once took responsibility for.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.