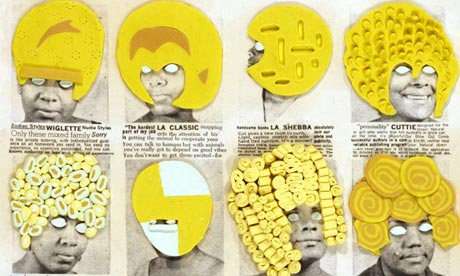

Ellen Gallagher’s Wiglette from DeLuxe 2004: ‘A very late-flowering strain of surrealism.’ Photograph: courtesy of Gagosian

The American artist Ellen Gallagher is admired to the point of reverence on the other side of the Atlantic. Her distinctive combination of politics and prettiness has been catnip for collectors and critics alike these last 20 years. For the latter, there is always so much to talk about – her range of references from Moby Dick and Sol LeWitt to Black Power and Detroit techno, her trademark restyling of 50s ads and 60s sci-fi movies, her evident if excessively elusive intellectualism – all appealingly couched, to collectors, in the delicate aesthetic of her paintings and prints.

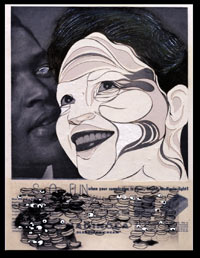

It is worth knowing about this high regard when visiting Gallagher’s retrospective at Tate Modern. It helps to explain the sheer scale of the event: almost 100 works, many of them multi-part, accompanied by a catalogue of eulogies by some of America’s finest art writers, and all kicked off by a gigantic blown-up reprise of Man Ray’s famous photograph of Matisse sketching an odalisque in harem pants on a couch with Gallagher’s own face pasted on to the model and Sigmund Freud in the role of Matisse.

You may guess that this photomontage has something to do with Orientalism, Otherness and race – Gallagher’s father was African-American – and something to do with sex, femininity, white male artists, couch trips, models and the male gaze (piquantly reversed, for Freud is absorbed in his drawing while Gallagher keeps a sharp eye on him). You may engage with its slipperiness, or not, all you like. But the effect depends at least in part on the artist’s own fame. It is vital the viewer should recognise not just Freud but Ellen Gallagher.

Prior knowledge of all sorts turns out to be a requisite for this show. An entire gallery, for instance, is hung with numerous editions of what appear to be pretty much the same work: sheets of lined exercise paper glued to canvases, sometimes lacquered, sometimes painted fetching colours and sometimes featuring racial caricatures of big lips and bug-eyes. These mouths and eyes are always tiny and sometimes so faint as to be spectral, which carries its own meaning. Gallagher describes them as “the disembodied ephemera of minstrelsy”.

But as for the lined paper – reams of it, regular, incessant – this has less to do with schoolbooks (or so the wall-texts indicate) than the refined serialism of American minimalists such as Agnes Martin and Sol LeWitt. These works from the 1990s hit a nerve in New York where some commentators praised them as an indictment of art-world racism and others found them too easy, too congenial to be more than critique-lite – if that is indeed what they were.

For these works are so wan and underpowered that it is (for me, at least) impossible to tell. And that is the way it goes for so much of this show. The lips and eyes proliferate, reappearing over and again in other combinations – strung together, piled high, strewn around in heaps, cut and pasted and over-painted with oil or gesso, repeated so that they look like patterns in African fabric. They are signs, they are signifiers; but after a few rooms they come to look like nothing so much as elements of Gallagher’s own visual vocabulary.

The artist is probably best known in Britain for customising advertisements for skin-lighteners, hair tonics and feminine hygiene from 50s African-American magazines such as Ebony and Sepia. These are all about personal transformation, and Gallagher duly transforms them. The eyes are scissored out – so they go, as you guessed, from black to white – scarlet lips are added and black hair turns blond with wigs of yellow Plasticine applied to the surface in weird permutations.

Some people find this look subversive, mordant or carnivalesque (they should try looking at the devastating montages of John Heartfield). The best that can be said is that it certainly derives from an old tradition. The 60 panels in this series that already belong to Tate Modern, collectively known as DeLuxe, are a very late-flowering strain of surrealism.

Why would anyone want to do the same thing over and over again? In Gallagher’s case, critical mass seems to be both an aesthetic and political objective. Everything teems, breeds and multiplies, spilling over from one series to the next. Everything repeats itself, presumably like history; everything connects, in life as in her art.

The minstrel lips reappear in the DeLuxe collages, the bug-eyes reappear in blond wigs swimming like tiny sperm in dark oceans. There is a consistent use of gold leaf, Indian ink, cut-outs, relief and gesso, fine ruled lines and elegant draughtsmanship pinning it all together. But to what end?

Gallagher’s latest works are underwater fantasies of a black Atlantis populated with the unborn descendants of slaves thrown overboard for insurrection. They are gorgeously glutted with biomorphs and gilded tendrils and faces so tiny as to be nearly invisible, surrounded with enormous areas of blue wash and pale (colour-free?) paper. Their sincerity as lamentations for the lost can hardly be in doubt. But the lost remain lost, alas, at Tate Modern because there are just so many of these works that the mind glazes over. It starts to look like a prolonged exercise in the making of exquisite fine art.

A certain fragility, shading into deliberate feebleness in the case of Elizabeth Peyton and Karen Kilminik, has been quite a trait of US painting in recent years. Ellen Gallagher has it too, if put to a quite different and much more serious end. But her intricate and ever-evolving aesthetic draws too much attention to itself. She has said that her work makes people “uncomfortable”. If only it had that power.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.