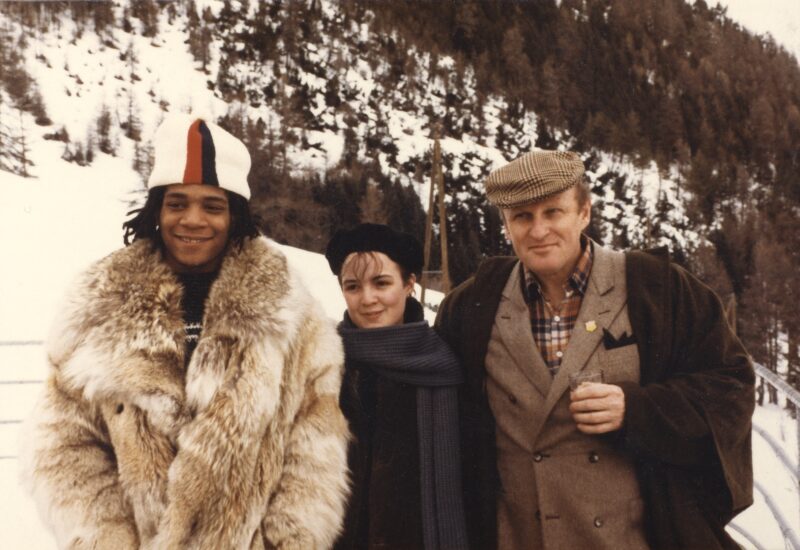

‘Fierce creatures’: James Capper’s Nipper, 2012. © James Capper/Saatchi Gallery, London

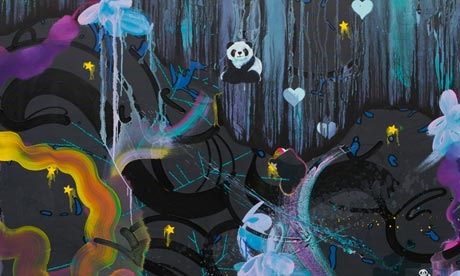

‘Abstraction breeds with Hello Kitty’: Fiona Rae’s Maybe you can live on the moon in the next century, 2009. Photograph: © Fiona Rae; courtesy Timothy Taylor Gallery, London

Fiona Rae is a heron in the landscape of contemporary British art – solitary, sharply focused and so motionless she appears rooted to the spot. Ever since she was shortlisted for the Turner prize more than 20 years ago, she has made the same kind of painting over and over again. The variations are no doubt colossal to her, but so fractional to the viewer as to appear almost imperceptible; she never seems to shift an inch.

This has nothing to do with style. After all, many abstract painters have their unchanging idioms, their drips, stripes or spots, their blurry oblongs, geometric forms or transparent veils, just as she has her high-chrome sampling. But still their permutations generally carry different meanings, moods or effects. With Rae, something else is going on (or not), and it’s good to have a sizable show like this one to try and deduce precisely what that is.

Her look is instantly recognisable and appealing: rich, lush and borderline kitsch. Swirly psychedelic colours are balanced with pure strong hues and pinned together with shapely black lines out of Walt Disney via Roy Lichtenstein and Patrick Caulfield. Quotations from other painters – Kandinsky, Pollock, Miró – appear freeze-dried on the substrate among squeegee wipes and fizzing explosions of colour.

Each canvas is glutted with motifs, riffs and teeming gestures, all tuned at different speeds according to the brushwork – thicker, heavier, more circumlocutory to slow the game down, quicker and finer to the point of evanescence. Rae plays with modernist flatness so much – what’s in front, what’s behind, what’s on the surface – she’s come to look like an old-style modernist herself.

But against that is the sampling of images and emblems, which has lately become cloyingly cute. Pink love hearts, glittery angels, a little dot-encrusted figure that looks like pastiche Chris Ofili: they recur from painting to painting like logos. There are dainty dogs and teensy koalas galore, sometimes peeping out from behind a skein of sub-Pollock drips in a coy game of hide-and-seek. Abstraction breeds with Hello Kitty. How can this even be grown-up?

But it is, of course, in its coolly sophisticated way. For no matter how spontaneous these jeux d’esprits appear at a distance, they are extremely practised up close. Everything is pinned together with precision, if not our old friend Photoshop, and one senses a steely purpose in each painting. Nothing is quite left to chance.

Certainly there are variations in motif – cacti, stick-on flowers, burlesque flourishes, numbers and even letters in telling typefaces. The most recent paintings have a space-age look – 60s fonts float alongside Tomorrow’s World digits in fields of fluctuating colour that get a certain depth from deepening hue or patches of twinkling black glitter. These works are spacier in every respect, and less is definitely more.

But this retro aesthetic is still a form of sampling, importing or reconfiguring; and so are the variations in brushwork. Several paintings have overtones of the sewing bee, of stitching, feathering, patchwork or appliqué. An ethereal blue painting with waterfalls of diaphanous white and pale pink has as its central character a little bear tumbling through space. The picture is called I need gentle conversations, and while the sincerity of the title may not be in doubt, the picture rather argues against it. The bear’s button eyes and stitched eyebrows follow after him, Manga-style, graphically disassembled.

Rae’s paintings are densely satisfying as momentary encounters but they can’t stand much scrutiny. This is not just because their separate elements suggest wild and wonderful freedoms – stars, birds and butterflies, lyrical lines and DayGlo colours – that are countered by her super-controlled execution. Nor is it that the eye cannot deal with so much to look at all at once.

It’s more that the mind cannot make anything much of these paintings because they recoil from that imperative themselves. They do not wish to amount to anything as large as an idea; they do not wish to add up.

One of the paintings has a sentence threaded through it, word by hidden word. It declares that The woman who can do self-expression will shine through all eternity. The tone of this is extremely hard to read. Given that the words are inscribed on a canvas pullulating with what might be self-expression (though who can say?), it could be surprisingly self-regarding; if the reverse is true, then it is empty rhetoric. Either way, the proposition is arguable, and that seems to be Rae’s fixed position, indeed her modus operandi as an artist – keep it all in the air; keep it all, endlessly, in play.

Rae’s ascent from Damien Hirst’s Freeze show to Sensation, the British Art Show and the Turner prize in her 20s, before becoming a Royal Academician in her 30s, was aided somewhat by Charles Saatchi’s early patronage. (Unlike some of her peers, Rae has the grace to acknowledge this is in catalogues.) And every time Saatchi shows a tranche of his latest purchases in contemporary British art, there is the faint expectation that he may have hit upon a new generation of YBAs.

But they don’t come along that often, and New Order is peculiarly dud. It has some unremarkable painting – wilfully bad in some cases, irretrievably weak in others – with the balance towards figuration and an unusually high quota of backsides in breeches, naked bottoms and outright bums.

Steven Allan makes paintings that look like old prints, dark and graphic; but this interesting idea is mainly used for rude pastiche. His carnivalesque banana man, with Klannish hood, exists to support a variety of puns: One Off the Bunch, Peeley Wally and so on. Amanda Doran makes obvious wordplay with The Semen, two sailors in a crude oily spatter.

British art is happily so international by now that one of the strongest artists here, Greta Alfaro, is Spanish. Her film of a last supper slowly consumed by vultures, its soundtrack like some medieval banquet of beaks clattering on salvers, was shot in a desert. And Israeli painter Amir Chasson‘s portraits of skewed faces are strangely disturbing.

The star of the show is James Capper, who has forged fierce new creatures out of industrial parts – dinosaur cutters, scimitar crabs and lumbering minotaur-mowers. Part-art, part-machine, some of these critters can climb or walk.

New Order offers no lessons about contemporary British art. It spots no trends – no obvious trends are waiting to be spotted – and it represents, as always, Saatchi’s own taste in art. What is striking is how precisely it echoes previous shows. It has its oleaginous oil portraits, the impasto extruded and flanged like some extreme hybrid of Glenn Brown and Frank Auerbach. It has its Richard Billingham-style photographs of small-town English life, and its nasty child-mannequins, as originally invented by the Chapman Brothers. What it lacks, tellingly, is anything as intricate or accomplished as the work of Fiona Rae.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.