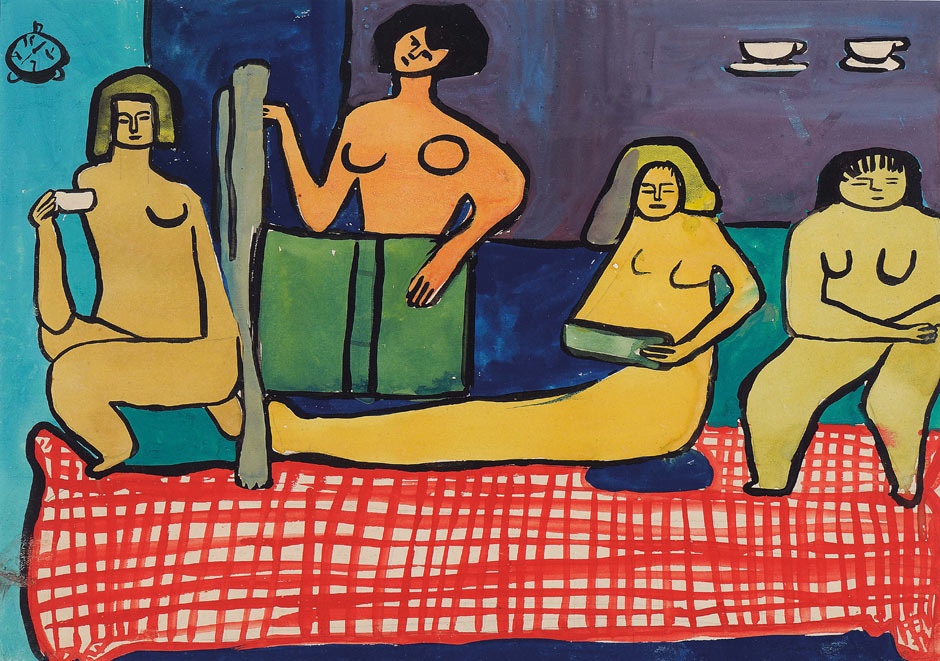

Les Peintres célèbres, 1948-49 by Saloua Raouda Chocair: ‘She takes Léger’s tubular belles and gives them some spirit.’ Photograph: © Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation

A bolt from the blue is not what one expects at Tate Modern. Unqualified revelations have never been the museum’s priority. Nobody goes to Bankside hoping to be astonished by a brand new name, a new artist, a new strain of art that has not yet been bruited on the international circuit all the way from Venice to Sydney to Basel. It does not deal in risks or experiments or artists without a press review to their name. It is powerfully attached to the status quo.

Or at least that was the case until last week. For the first time in its 13-year history, Tate Modern has devoted a solo show to an artist who can confidently be described as completely unknown in Britain. She has never had an exhibition here, still less shown any of her paintings, drawings or sculptures here or practically anywhere outside her native Lebanon. Saloua Raouda Choucair is an extraordinary new name. She is also in her 97th year.

Choucair was born in Beirut in 1916. She has never stopped making art despite the fact that her earliest success – in Paris in 1951 – was more or less her last. She studied in the studio of Fernand Léger in Paris and was a pioneer of abstraction (or, to my mind, semi-abstraction) in Lebanon, but did not sell a single work there until she was in her 50s.

Many artists have endured similar struggles but few have found themselves simultaneously quite so thwarted by political strife. One of the paintings in this show is pocked with holes from a bomb blast during the civil war that left Choucair’s husband deaf, and the Beirut art scene has been so devastated by violence that the galleries that represented her work have shut down in sequence over the years.

Of all the monumental sculptures she dreamed of making, only the beguiling prototypes exist. And in Beirut itself, all that survives of her public art works is a series of 17 stone forms that used to huddle together in a familial crescent, and upon which families used to sit, but which have been split in two by Solidere, the company in charge of rebuilding the city centre; an art work in divorce.

The show opens, as so often, with a youthful self-portrait. But in this case the sharply intelligent young woman all chopped about in post-cubist style, green shadows beneath the eyes, nameless urban jungle behind her, is wearing a headscarf. It is 1943 and Choucair has not yet left Beirut for Paris and seen the European avant garde at first hand. When she does, though, it will be with far less traditional responses.

Her reaction to Léger’s art, for instance, is to take his tubular belles and give them some spirit. Her dark-eyed models don’t just sit there holding the pose without any clothes, they drink espresso, converse and read books (in one case, books on great artists, and we may guess who). They are never content to remain passive within their heavy black outlines; there is always a sense of imminent movement.

A vein of humour is rare enough in art but it runs consistently through this show. Chores, as it’s called, could easily pass as some early modernist painting, all compressed forms and wild distortions. But if you look closely you can see that the bottle-washer’s head really is inside the giant wine glass she is washing; that the woman who’s doing the ironing is labouring away at the stretch of cloth that has been flattened against the substrate in true cubist style so that it doubles as the chore itself but also as her whole environment.

There are plenty of jeux d’esprit in the opening galleries, but the major work here is an exquisite little painting called Paris-Beirut. An Islamic star, Cleopatra’s Needle, the colours of the desert, the Arc de Triomphe: all are reduced to their essential forms and held in perfect balance in a picture as condensed as a sonnet. The Arc opens as a portal in both directions – which way will Choucair turn, should she go or should she stay?

In the event she returned to Beirut and a great stream of gorgeous syncopated abstracts that are based on mathematical permutations but fly free of science. Thermal currents, reflections, quivering trees, dancing figures; the catalogue places due emphasis on the strictly non-figurative principles underpinning the art, but paintings are their own evidence and these speak constantly of the visible energies of life.

Choucair’s sculptures fuse Islamic design with modernist traditions. Like her paintings they are small-scale, spry and ingeniously balanced. Two roundels fit together, making a friendship. Six molar-like lumps fit together, and a bridge is established. She has many vertical forms constructed out of idiosyncratic blocks that irresistibly evoke mid-rise towers. One of these sculptures, carved out of wood, with recesses, reliefs and louvred apertures, seems to vibrate from top to bottom with interior life – unseen human existence.

The last room has beauty in abundance, numerous sculptures created out of gossamer thread, spun steel and glass. Some are planetary, evoking eclipses and starbursts. Others have affinities with womankind – corkscrew curls, metal bows and gyrating curves – and the quirkiest are highly strung, shivering excitedly as one passes. Even without any knowledge of the Sufi principles apparently underlying this art, one has the sense of a free and humorous spirit perpetually at work.

That Saloua Raouda Choucair has had to wait a lifetime for such a show is shocking but standard. Western museums are resolutely conservative. But perhaps Tate Modern is about to change direction, for this is the first in a series of exhibitions of Arab and African artists whose work is cherished at home and entirely unknown here. Fittingly, it’s on for half a year and is neatly positioned among the themed galleries on level four so that browsing crowds will come across it more easily. Choucair profoundly deserves it.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.