Contrada Vallecupa, Colonnella, Abruzzi, Italy (2011), by Mishka Henner

Mordantly funny … Untitled, from the series The Afronauts (2011), by Cristina de Middel (detail)

Google Street View has recorded the world. The camera-toting vans have seen astonishing things, from mountain lions patrolling parking lots to armed holdups, elks running down the highway, accidents and murders.

Many of the images Street View has accidentally recorded have been sampled and published by the Canadian photographer Jon Rafman. Among his immense trawl of images are several of sex workers selling themselves at the roadside. I have seen some of these women myself: on sun-blasted Spanish roadsides and, once, on a Polish highway on the way to Treblinka.

Mishka Henner, a Manchester-based Belgian photographer, has gone to the same source as Rafman for his No Man’s Land, a series focusing on kerbside prostitution in Italy and southern Spain. Bikini-clad women stand at roadsides in the sun. Sometimes they come equipped with parasols and garden chairs, touting for passing trade – men in trucks and strangers in family saloons. They pose in the heat and hang around in the dust, loitering in whatever shade they can find, their faces blurred by software.

A faint soundtrack of birdsong and passing traffic filters into Henner’s display in this year’s Deutsche Börse Photography prize show. On one wall is a girl in the middle of nowhere, up an unmade track between fields. The images raise all sorts of questions. Are the girls local or migrants? How much do they make? How dangerous is their work? What led them to these dismal spots, anyway? On a video, we watch the girls approach and recede as we pass them by. We speed away as ignorant as we were before.

A sociologist by training, Henner presents (or rather, re-presents) the images without comment. Henner annoys me. For other projects, he has digitally removed the figures from Robert Frank’s The Americans, and overlain Gerhard Richter’s blurry, photographically based paintings with words and phrases taken from Ed Ruscha’s work. Ho ho, you say. Real complexity lies elsewhere.

A kind of arch and sometimes bleak humour runs through two further projects in the show. The images and texts that canter around the walls of Spanish photographer Cristina de Middel’s The Afronauts, a reconstruction and reinvention of the 1960s Zambian Space Program, tell a fragmentary story of a doomed attempt to send African astronauts to the moon and Mars. If America and Russia could have space programs, why not newly independent Zambia?

It was never going to get off the ground. De Middel’s photographs, drawings and re-photographed letters conflate original material with her own reconstructions and fantasy. A space camp shelters under a boabab tree; cosmonauts wander through a village of straw huts; a man in a wax-batik patterned spacesuit struggles through a cane field. Yinka Shonibare has presented a family of astronauts in similar garb floating in mid-air. What goes around comes around. All this works better in the little self-published book De Middel made of her project – now out of print and selling, I am told, for more than £1,000.

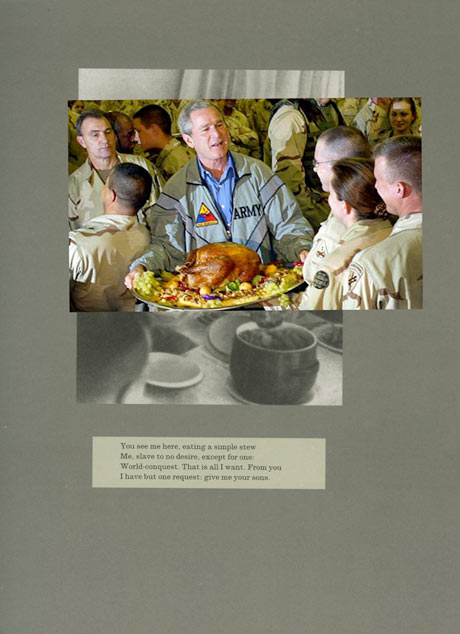

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin have taken Bertolt Brecht’s 1955 publication War Primer as source and inspiration. Published in what was East Germany, War Primer used second world war photographs, mostly from Life magazine, and accompanied each one with a short rhyming epigram, by Brecht, as comment and counterpoint. Using the original photographs as background, and keeping the original epigrams, Broomberg and Chanarin have overlaid the grainy black-and-white shots with more recent images from 9/11, Palestine, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and elsewhere.

It’s a rich and mordant compound. Hitler eats a nourishing vegetarian stew, the image overlain with George Bush bringing a Thanksgiving dinner to US troops in Baghdad. Brecht’s epigram reads: “You see me here, eating a simple stew/ Me, slave to no desire except for one:/ World conquest. That is all I want. From you/ I have but one request: give me your sons.” There are conjunctions of Abu Ghraib and a US marine with a dead Japanese soldier; Hitler ranting, and Donald Rumsfeld riding a unicycle; a US soldier surrounded by German civilians, overlain with a kid in a Halloween suicide-bomber outfit, shoebox bombs on his chest, scarf on his head, his finger on the trigger.

Published as a book, War Primer 2 is a powerful rereading of Brecht’s East German original in the light of recent history. Poring over the pages – each spread in its own vitrine – is a salutary experience. Time seems to concertina.

So it does, too, in the selection of Chris Killip‘s black-and-white photographs of working-class life, mostly shot in the British north-east during the 1970s and early 1980s, although the earliest was taken in Killip’s native Isle of Man in 1973. Farm workers load a threshing machine. There’s a pair of dogs, and winter sunlight, men with pitchforks and filled sacks being tied. We could be looking back a hundred years.

Killip is good at photographing work and the lack of it: hanging about, futile idleness and empty days, people with more pride than hope. For all their social observation, and the despair and tough lives they often portray, Killip’s photographs are enormously rich. Their emotional range as well as their visual sense – their composition, cropping and deceptive straightforwardness – is enormously affecting. Killip can be funny, too: especially in the shot of elderly women displaying their commemorative Silver Jubilee tea-trays in North Shields in 1977.

Then you come to a man with the sun on the back of his coat, staring at a brick wall on a litter-strewn windy pavement, his shadow swept along with the rubbish at his feet. Someone has chalked the words “true love” on the wall. The situation is one of blankness and emptiness. What matters is that Killip recognised this moment of enormous, ambiguous presence. It is a photograph full of time.

It’s 30 years since he took these photographs, and Killip probably doesn’t need a prize. But despite the decades, we still live like this. Not everything is digitised or snapped on Street View. He should win because his work is still valuable. Much of the other work here won’t be, in 30 years’ time.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.