The Happiest Man is an overwhelming experience. It takes place in a vast industrial bunker, pitch black except for the light streaming from a monumental screen. Old cinema seats stretch out like a ghostly audience, watching the movies forever in this subterranean dream. Towards the front stands a curious little house, its door ajar, revealing a narrow bed and table set for tea. It’s as if someone has built a home right there to get the perfect view, to live as close as possible to the silver screen.

The films showing on this screen are dazzling, powerful and rapturously joyful. They reveal another world, a Russia of the beautiful past in which everyone is working, and singing, in harmony. Men and women shovel mountains of shining grain, their chorus rising to the skies. Boys in peaked caps whistle their tractors across the motherland. A cartload of stunning girls, perched on top of the prodigious mound of watermelons they’ve just harvested, sing so melodiously they draw the men home from the fields. A man lilts a lament to a steamboat sailing away down the Volga, perhaps never to return. A handsome husband and wife in a pony and trap duet their way bravely home beneath a storm-blackened sky. A whole chorus line in headscarves and boots strides cheerfully towards the camera, looking like a Soviet poster come alive. Everybody sings, all the time.

What you are watching is effectively a combination of communist propaganda film and Hollywood musical, with all the make-believe that both entail. The woman in the trap is as good as Judy Garland, the man on the banks of the Volga better than Gene Kelly. Each face is vividly beautiful and healthy. The panoramas are stunning, slightly faded but still shot through with the glowing colours of Oz; immense wheat fields stretch out into the golden distance, dotted with poppy-red Russian skirts.

But there is something strange about the speed at which everyone moves, like the hectic action of silent movies. At first it looks as if the films are just running slightly too fast, but after a while you realise that the sound and vision are in perfect accord. These performers really did scythe and thresh and stook corn for the cameras at this superhuman pace. It sends up thoughts of Soviet harvest quotas, and that sends up thoughts of tyranny and death.

Whoever lives in that curious little house, of course, can only see the view through the window, and the view is only ever what appears on the screen. There is nothing else in the world, nothing beyond this beautiful vision of how life might be, should be, could be – perhaps even really is – somewhere out there in Mother Russia.

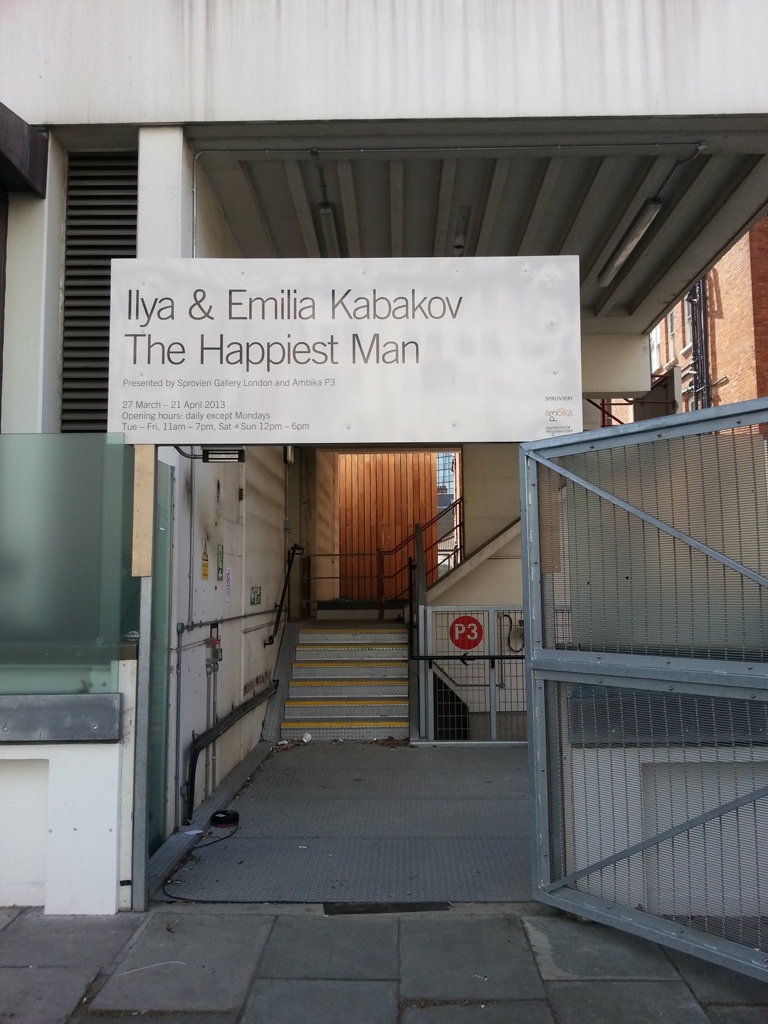

The Happiest Man is by Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, the most famous and original artists to have come out of the former USSR. Once again they have created an unforgettable vision of Russian life that nonetheless draws upon a universal metaphor. The man who lives in the house is trying to escape from reality; he does what we all do, but in perpetuity – he goes to the cinema.

The Kabakovs are pioneers of “total immersion”, the kind of walk-in installation – a perfect facsimile of an office or apartment, for instance – that has inspired so many contemporary artists from Miroslaw Balka to Mike Nelson. Their evocation of a communal living in a Russian tenement, elaborated through a labyrinthine maze of dead ends, was one of the marvels that launched Tate Modern.

The Happiest Man is similarly simple in its methods yet rich in its metaphors. It transports you to “Russia” in the 40s and 50s, and it takes you out of time in another way. In the little house it could be any time in the past 100 years – the clock has stopped, the crockery and the clothes are timeless. The man who lives there has taken refuge in cinema’s continuous present, its endlessly unfolding stories.

But the books in the house suggest all sorts of longing – Theodore Dreiser’s tragic Sister Carrie, Hermann Hesse’s spiritual Siddhartha – and the paintings on the walls are full of yearning: moonlight over the ocean, twilight in summer. By the door is a little watercolour of a cart disappearing down a road into the golden hereafter just like the ones in the films.

What is so extraordinary is that these propaganda films return the homage to art. A sequence of stills – woods, cows down by the river, the immense sky over the Volga – are composed like the 19th-century landscapes of the great Russian painter Ivan Shishkin. All the close-ups look like portraits. Peasants gilded by the last rays of the sun look like Millet’s heroic harvesters, bearing both sadness and hope.

The Sprovieri Gallery has paintings by the Kabakovs, Two Mountains, beautiful visions of misty mountains. One shows a mountain doubled and inverted, its reflection hanging down from the sky as if the world had turned upside down; that fantasy every child has of living on the ceiling, of another world where everything is more marvellous but looks just like this one. The connections between these ethereal paintings and the Ambika 3 show are evident and profound.

For the films in The Happiest Man are simultaneously works of art – superbly shot, epic in grandeur – and works of outright propaganda. The two are one and the same. They take you back to another world of camaraderie, love and joy, mutual help and inspiring music: a better place. You could live there for ever, or so the little house implies.

And yet these same people who fill the screen, who look so real, are just acting out a communist fantasy. Everything appears to be taking place in the present – cinema’s great magic – yet none of this would ever come to pass. The Kabakovs have made a most poignant metaphor out of movies: the illusion holds as long as you believe it. Utopia fails yet the dream survives.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.