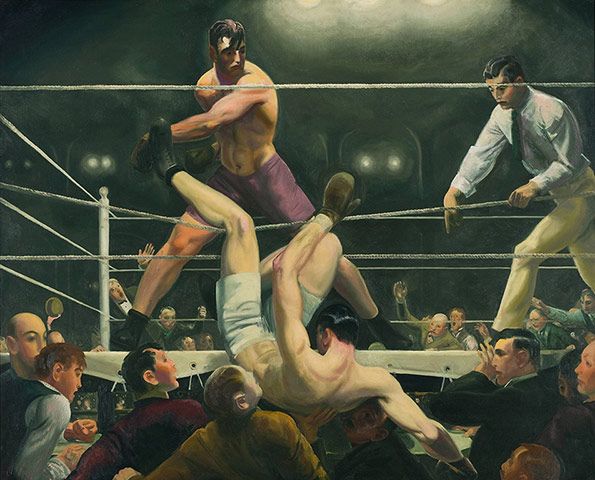

Dempsey and Firpo (1924) Photograph: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

American painting began with the contemplation of virgin nature: the forested clefts of the Hudson valley, the radiant, skyscraping heights of the Rocky mountains. But by the end of the 19th century this idyll had been spoiled by fuming, stewing industrial cities, and “Mother Nature”, as the novelist Theodore Dreiser sarcastically put it, was now a Darwinian matriarch, spawning “humanity in massed numbers” and goading indigent mobs into combat with the “grinding and almost disgusting forces of life”.

Those forces – greed, need, the rebellious energy of a population enslaved by machines – were George Bellows’s subject. Arriving in New York from Ohio in 1904, he painted the city as a site where, as his mentor Robert Henri said, “the battle of human evolution is going on”. The weather does its best to massacre his New Yorkers, tormenting them with frigid winters and suffocating summers; their response to the vital challenge is to show off the mettlesome resilience of the human animal.

Urchins hurl tin cans at each other in slum gutters, which they share with scavenging curs. Individuals are effaced by Dreiser’s mass: all that can be managed is a numerical total, as when in 42 Kids Bellows swiftly tallies the figures – “kids” not “lads” or even “boys”, suggesting their closeness to a litter of cubs or pups – who use a derelict pier as the diving board from which they hurl themselves into one of Manhattan’s turbid rivers. Crowds with faces blurred and smeared into bestial ferocity gather to watch boxers brutalise each other as they act out a Darwinian parable about the survival of the fittest. The political system is the continuation of pugilism by other means: election night in Times Square, documented by Bellows in charcoal and murky crayon in 1906, is a carnival of indiscriminate boozing and brawling, shoving and groping.

Bellows found sublimity in urban excitements that Dreiser called “gross and cruel”. For European romantics, the sublime meant the ego’s elated reaction to the infinitude of sea or sky; in American cities, it dramatised the struggle between collective humanity and an environment that was being churned up and reshaped by engineering.

Bellows had no need to measure himself against the wild natural spectacles that earlier painters – Frederick Church at Niagara Falls, Albert Bierstadt in Yosemite – strained to celebrate on widescreen canvases in gaudily iridescent colours. For him, America’s destiny was manifest in the building works for Pennsylvania station, which brought the railway into Manhattan by tunnelling under the river and gouging out a vast pit in the city’s granitic bedrock. One view of the man-made crater in winter makes it look like Niagara, with the torrents stilled by ice and snow; another, looking steeply down into the gulf at night, sees it as a Grand Canyon sliced open by human will and dogged machinery in a few short months, rather than the millions of years it took the Colorado river to nibble its way down through the rock in Arizona.

Bellows even found his own local equivalent to the vertical habitat of the Navajos, who – in that other America, the picturesque frontier – carved houses on narrow ledges in Canyon de Chelly. Cliff Dwellers is the title he gave to a painting of a tenement and its stacked inhabitants. Dreiser marvelled at the way that Bellows’s splotchy brush multiplied a few dozen distinct figures and suggested that hundreds were crammed into the broiling darkness: here was another exercise in the statistical sublime, exposing “life in its blind dumb masses”, with endless quantities of guzzling infants pouring from the bodies of those slum mothers who squat in the street to nurse their offspring.

In a series of flag paintings by Bellows’s contemporary Childe Hassam, patriotic pennants flap in the bright air on fashionable Fifth Avenue. Cliff Dwellers has a satirical corollary: on a washing line strung across the narrow street, the slum tenants have hung out their laundry, hoping for a breeze to stir the frayed and greying undergarments. Bellows waved no flags, and had no use for Walt Whitman’s urban pantheism. The Brooklyn bridge, extolled by Hart Crane as the city’s resonant harp and worshipful altar, appears only once, as the backdrop to a scene of garbage disposal, with sanitation workers dumping loads of grubby snow in the river.

The Royal Academy show – a reduced version of an exhibition already seen in Washington and New York – is inevitably dominated by the boxing pictures, which extend from Stag at Sharkey’s, a gruesome bout in the backroom of a sordid Irish saloon, to Dempsey Through the Ropes, a nobler tableau that marks the change from no-holds-barred, illicit battery to the organised sport of prizefighting. At his violent best, Bellows applied paint as if it were a primal fluid: the flesh of his boxers is almost obscenely slick with sweat, and their bloodied ribs look like carcasses dangling from hooks in a butcher’s shop. Men, in the naturalist view, are just cuts of tenderised meat.

The muscular tension and fraught distortion of the figures in Stag at Sharkey’s gives them an unexpected modernity. The painting dates from 1909, four years before the Armory Show brought cubism and post-impressionism to bewildered, scandalised New York and caused Theodore Roosevelt – a president as well as an art critic, whose gospel of “the strenuous life” Bellows often seems to be illustrating – to rail at the lunacy of “European extremists”. Roosevelt particularly scorned Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, and wondered if the painter belonged to the school of “Parallelopipedonists, or Knights of the Isosceles Triangle”. But Bellows had already shown how a body can be taken to pieces –not dissected by an artistic theory as in Duchamp’s case but bent, flexed and almost turned inside out by desperate physical strife.

Bellows was enraptured by muddy, sweaty modern life; he may have been scared by the sight of modern art when he eventually got to the Armory, since he soon retreated into gentility or grandiosity. He now painted tennis tournaments, not matches in the ring between thugs with mashed faces. Love of Winter is a panorama of well-dressed, rugged-up skaters: insulated against the elements that oppress the underclass, the rich can afford to enjoy bad weather. Then, during the 1914-18 war, he registered humanitarian outrage in a sequence of huge, windily rhetorical history paintings in which helmeted Huns thrust bayonets into corpses, use naked hostages as a barricade, and deflower Belgian maidens. The trouble is that the indignation here feels uncomfortably close to the unholy glee of the sadistic boxing matches. War, as the German marauders claimed, is one more outlet for our reserves of combustible energy, just like sport. I have the same suspicion about some ghastly lithographs of lynching and electrocution. Was Bellows protesting against injustice or enjoying another display of energy running amok?

The later works in the show are dire: portraits of rich crones, fluffy socialites and their obnoxious lapdogs, plus some magic-realist landscapes that are too fancifully magical to be realistic. When Bellows died in 1925, aged only 42, Edmund Wilson praised his appetite for ugliness; but by then he had acquired a taste for beauty – anodyne, expensive, artificial – and it proved fatal to his work.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.