Jack Bell (a London-based gallery focusing on art and photographic practices from the African continent) is currently showing work by South African artist Roelof van Wyk. The show opens tonight (5 March), and runs through 16 March. For more about Van Wyk, and Jack Bell visit www.jackbellgallery.com. Yvette Greslé talks to Van Wyk about his photographic work: the portraits (‘Young Afrikaner – a Self-Portrait’), and a new body of landscapes.

‘Young Afrikaner’ was included on a major exhibition of South African photographic practice at the Victoria & Albert Museum in 2011. The show – ‘Figures & Fictions: Contemporary South African Photography’ – was curated by art historian Tamar Garb (University College London), and the V&A’s Senior Curator of photography Martin Barnes. Van Wyk, who originally trained as an architect, is currently working on an M.A at Goldsmiths. In South Africa, he was a finalist in the Spier Contemporary competition (2010). He was also a finalist in the International Photo Awards (2010).

The Jack Bell show includes a book signing: The 2012 book ‘Jong Afrikaner: A Self-Portrait’ (or ‘Young Afrikaner’) documents Van Wyk’s photographic series and is published by Fourthwall books (Johannesburg). Also see the 2011 exhibition catalogue ‘Figures & Fictions: Contemporary South African Photography’ published by Steidl and the V&A (London).

‘Young Afrikaner’ focuses on a particular aspect of South Africa’s complicated history. South Africans described as Afrikaners are, (in the imagination of South Africans and international communities alike) synonymous with the apartheid regime, and race-based violence. Van Wyk (himself an Afrikaner), grapples with the nuances of colonial and apartheid violence, its inheritances and its authoritarian imposition of a state-sanctioned National identity.

Similarly, to many South African artists of his generation (he was born in 1969) his work is concerned with what it is to be an artist in South Africa in the 21st century: he is part of a generation calling for a new kind of politics, a generation as exhausted by the past as it is aware of its baggage. A heightened self-awareness is apparent in the work of many younger South African photographers. Highly staged images (drawing from photographic languages that often cross boundaries between art, fashion, advertising and the media) speak of defiant self-fashioning in the face of insidious stereotypes.

South African contemporary art is deeply political in its impetus, and artists often explore complex political questions (and the violence of the country that defines them). This exploration often begins with the self. In a country where the question of representing and speaking on behalf of others is so fraught, self-representation and self-exploration is a strategy that opens up a space for critical reflection. Van Wyk’s work searches for a space within which to self determine, while simultaneously recognising the legacy of the apartheid regime: its entrapments, and its claustrophobic, de-humanising attempts to contain and control social relations across strictly defined racial groupings.

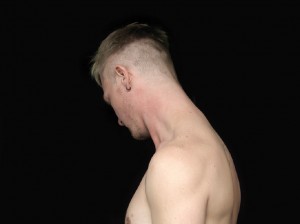

Placed within the context of South Africa, the series suggests a photographic language that draws attention to the politics of picturing subjects defined by ethnicity. Here the subjects are all Afrikaans speakers who would have been classified white by the apartheid regime, and the title describes them for us in the fashion of the ethnographic image. Van Wyk searches for a way of resisting the visual vocabulary of stereotypes and type-casting, as he deploys its language. This is a difficult edge: the line between re-inscribing and resisting visual languages so politically laden. But the highly staged illuminated head and shoulder shots (of unclothed subjects) against deliberately dense black backgrounds produce other readings too. Van Wyk’s photographs are in dialogue with international photographic practices situated within the framework of contemporary art, as a critical practice. His work deploys a historical language of portraiture, and self-conscious staging. The figure against a black background is to be found in fashion photography, but it is also part of Northern European painting traditions that reach into the 16th century. Van Wyk’s deliberate construction is a visual strategy intent on thinking about the ways in which we learn to look at images. Perhaps our interpretation of his photographs says as much about our own subject position, and our own inherent assumptions, and frames of reference. It is difficult, knowing the history of South Africa, not to see race. The backgrounds are unreadable, as their darkness lends itself to story-telling and myth-making. The figures that perform for our view are constrained by their ethnicity, as they are human beings about whom we know very little.

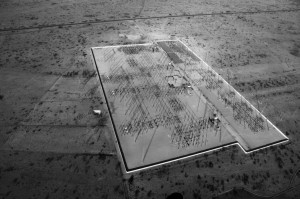

A body of landscape works in progress invite a similar kind of close observation. Drawing from an archive of landscape, reconnaissance and war photography, Van Wyk focuses in on sites of conflict, and violence. South Africa has an embattled relationship to land: recent events publicised by the media draw attention to the violence of farms and mines, and the inequalities that still persist. Van Wyk’s landscapes in dialogue with the historical violence of capital, ownership and war, relate as much to South Africa as they do to international politics and the struggle to be visible: to be recognised as a citizen and a human being.

What brought you to ‘Young Afrikaners’?

I wanted to start tracing my own history. The whole body of work is a self-portrait, and my own tenuous links to each of the individuals I photographed. I chose them deliberately. Through the people I photographed I projected who I am as an Afrikaner. Each person’s story came to speak a little to who I am. It became a way of tracing history. Every person I photographed had a family history that went back to a moment in time (the Anglo-Boer war or the arrival of ancestors at the Cape, from Holland, in the 17th century). Apartheid enters this history: the grandfather of one of the people I photographed was Winnie Madikizela-Mandela’s lawyer in Brandfort in the Free State (she was banished there in 1977). The grandmother and Winnie Mandela became friends: she accompanied her husband to meetings (he could not be alone in a room with a black woman). The two women started to trust each other, and started exchanging letters. The relationship is documented. Every story traces a certain history.

I’ve always looked at people’s faces as a landscape. I am fascinated by faces. Not the aesthetic aspect. Writers often focus on my photographs in terms of an aesthetic: the white idealised face staring into the distance looking for a lost land and stuff like that. I’m just interested in faces, and how we read through faces. It’s the same with landscape. If you’re looking only at the surface of a landscape you lose so much about what that landscape can tell you. Recently, I started photographing landscapes again: sites associated with historical conflict and struggle, and relationships between people and the land. In South Africa, these conflicts carry on: the events of the Marikana mine or the farmworkers’ strikes in Franschhoek (near Cape Town). There is always a link between people and the land.

What shapes your recent interest in landscape?

I come from a little gold-mining town called Kinross (in South Africa). Kinross is named after a Scottish town. The Scottish town is beautiful (lakes and so on). The town I come from is about mining and farming. My interest in landscape (in land) comes from my relationship to the town I grew up in: the farms are all about the land and how you work it. Mining is all about what lies underneath the land and the landscape. In 1986 there was the Kinross mine disaster: 177 mine workers were killed. It was a big event. It stuck in my memory.

How did you start photographing the landscapes?

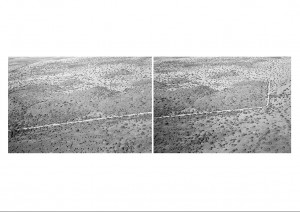

It began with a conversation: with one of the ‘Young Afrikaners’ – Alexi Monroe. One of his ancestors is Scottish. During the Anglo-Boer war he came over as part of a Scottish regiment, and after the war stayed and married into an Afrikaner family. Alexi told me this story and it inspired me to go and photograph the site of a battle in Kimberley (the Battle of Magersfontein, in 1899, where Scottish regiments fought the Boers). I am interested in moments where multiple frames of reference cross over. I photographed the site of the battle but something seemed to be missing. I started reading up about the Anglo-Boer war, and I found this beautiful image taken of a landscape (a reconnaissance photograph from the Royal Engineers). The British sent photographers across to document the war (it’s well documented photographically). Photographs were taken from a balloon, far enough not to be shot down. And then the engineers would map out (using the photograph) the whereabouts of the Boers.

I went up in a helicopter and started photographing from the air. You get an oblique view, you get this landscape, and you can really feel how big it is. South African landscapes are vast. How do you capture that? I’ve made about 6 helicopter trips over the past two and a half years. Each is of a site: Kimberley, Marikana etc. The photographs show you inequalities: squatter camps where the miners live, and elsewhere brand new infrastructure owned by the capitalists and the mining bosses. We’re not seeing progress. We’re seeing inequality that exists in the landscape. In Marikana you can see mine dumps rising out of the earth: monuments to mining, colonialism, capitalism. Looking at the landscapes you start seeing how inequalities are inscribed. What you can’t see in beautiful landscapes are undercurrents of resistance and violence, occupation and ownership, dislocation and migration.

You’re doing your MA at Goldsmiths. What is interesting for you about being here in London?

Displacing or dislocating yourself is incredibly valuable because it shifts the ways in which you look, you aren’t bound by the things that hold you back in South Africa.

So people look at you as a person (Roelof van Wyk) as opposed to a white man, or an Afrikaner?

Yes. You cannot get past that in South Africa. No matter what you do.

Your work emerges out of a research process that includes the internet, history archives and libraries. What do you think is interesting about an artist’s relationship to a historical archive?

The archive inspires making. For me the archive inspires picture-making. You can take photographs of anything but what makes you decide which are the images with meaning? The work of an artist is to reveal what is invisible. One of the questions I ask is how did something like apartheid come to exist – not historically but humanly?