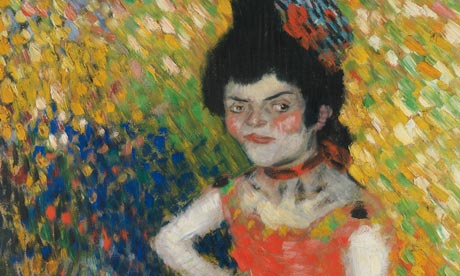

Death at a funeral … Picasso’s tribute to his friend, Casagemas in His Coffin (1901)

Raw young genius burns gloriously in Becoming Picasso at the Courtauld Gallery. This small but incendiary exhibition puts us side by side with a gifted wild boy in his 20th year, through a formidable array of superb paintings lent by public and private collections that includes Picasso’s Child With a Dove, which will probably be sold abroad soon despite the imposition of a temporary export ban last summer. British billionaires! Go and see this scintillating exhibition and see why your money would be well spent saving this modern icon for the nation.

It is not the only painting here that lodges in your imagination like a missing piece of the world, or yourself, at last fitting in its allotted place. Picasso is inevitable. His art, with its thick (yet always delicate, always correct) black outlines and piquant palette of turquoise blues, volcanic reds and sunflower yellows, takes shape in front of you at this exhibition. Arriving in Paris from his native Spain, untried and unknown, he dived into the world of Montmartre, which had already been made famous by Toulouse-Lautrec. The first paintings here take Toulouse-Lautrec’s themes and shake them violently to produce a febrile, intense, primitive remix of the dying 19th-century’s art. Picasso’s painting of a dwarf dancer, La Nana, on loan from the Picasso Museum in Barcelona, is something I will never forget – though part of me wants to.

An appetite for the grotesque would pervade Picasso’s entire career, from the unnerving clown face of Bibi la Purée, lent to this exhibition by the National Gallery, to his last self-portrait in 1972. He found plenty of raw material among the brothels and drinking dens of Paris, and within months was painting not just gifted essays in Bohemianism but profound mythic visions of a life on the edge.

Harlequin, thin and hungry and white-faced, twists his diamond-patterned body like a melancholy serpent, while a woman with cheeks pared to the bone clutches herself as she broods over her absinthe. The people of Montmartre are transfigured into eternal symbols of loneliness and longing in these great urban paintings.

The exhibition ends with personal tragedy and artistic triumph. While young Picasso was finding inspiration in a Parisian low-life of sex, drink and drugs, his equally ambitious Spanish friend Carles Casagemas came too close to the flame: he fell obsessively in love with a woman called Laure Gargallo, known as Germaine; she rejected him and he committed suicide. Picasso mourns Casagemas in the two last paintings in the exhibition. The Burial of Casagemas uses, in a mocking, ironically religious and Spanish way, the visionary style of El Greco to lament his friend – but the heavenly revelation is populated by prostitutes in stockings. This tableau anticipates his 1907 masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

In an unforgettable painting, Casagemas On His Deathbed, the young man’s features are hollowed and purified by death. Picasso has got the blues – and the blue period has begun.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.