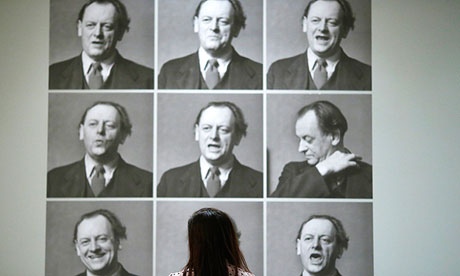

Photographs of Kurt Schwitters performing his poem Ursonate, at Tate Britain in London. Photograph: Andrew Winning/Reuters

PLEASE NOTE: Add your own commentary here above the horizontal line, but do not make any changes below the line. (Of course, you should also delete this text before you publish this post.)

He is often portrayed as a tragically isolated artist, shamefully neglected during his eight years in Britain, but a major new show devoted to the German artist Kurt Schwitters will present a very different picture. Even his time incarcerated in an internment camp was not without its rewards and pleasures.

Tate Britain will on Wednesday open the first major exhibition examining the later work of a Dadaist artist now regarded as one of the true greats of 20th-century modernist art, whose abstract collages and concrete poetry were an enormous influence on later generations of artists.

Schwitters is best known for his collages using everyday stuff, everything from bus tickets, string and newspaper cuttings to the label for a tin of peaches. What might surprise some visitors is how brilliant a figurative painter he also was, with the show exhibiting several portraits and landscapes from his later output.

The show aims to explode a few myths about Schwitters. Emma Chambers, Tate Britain’s curator of modern British art, said: “He is often seen as this isolated genius. But he was actually a very sociable character. He put huge efforts in to trying to make connections when he came to Britain.”

The exhibition, which features more than 180 works, traces Schwitters’ journey in Britain from an internment camp on the Isle of Man during the second world war to the London art scene to the Lake District where he began work on his now-famous Merz Barn until his death in 1948.

The Hanover-born Schwitters fled Germany after falling foul of the Nazi regime who condemned his work as “degenerate”, eventually arriving in Leith in 1940 on a Norwegian icebreaker.

He was detained as an enemy alien and interned in Hutchinson camp in Douglas on the Isle of Man – a place that turned out to be less gruesome than Schwitters might have expected.

The show’s co-curator, Jenny Powell, said that by sheer coincidence, there were several German artists in the camp and a man in charge, Captain HO Daniel, who positively encouraged their efforts.

Schwitters’ impromptu poetry recitals and storytelling raised spirits in the camp and his positive frame of mind might be best shown by a landscape painted from his attic room high in the camp with no obvious signs of it being a place of imprisonment. “I think it’s rather lovely,” said Powell. “Schwitters would paint the views above the barbed wire towards the sea.”

He also managed to make some money by painting portraits of his fellow enemy aliens, money that would prove extremely useful in his lean later years.

Also going on display is the leaving present given to the camp commander Daniel, containing paintings and sketches by the artists, who were profoundly grateful for the enlightened regime. Not going on display are the sculptures he would make from porridge – “they haven’t survived, it’s a real shame,” said Powell.

The show examines his London years, reuniting a group of works that were shown in his 1944 solo show at the Modern Art Gallery. Visitors can also hear examples of his sound poetry with a recital of Ursonate and the fantastic lines: “Oooooooooooooooooooooooo/dll rrrrr beeeeee bö/dll rrrrr beeeeee bö fümms bö.

Schwitters moved to the Lake District in 1945 and the show tells the story of one of his best-known projects, the Merz barn, in which he set about turning a stone barn near Ambleside into a work of art in its own right.

Penelope Curtis, Tate Britain’s director, said the show’s focus was very much not on the idea of exile, but on Schwitters’ remarkable creativity during this eight years in Britain. “He was very prolific when he was in England, he did a great deal of work – and it was very good work.

“We didn’t want to subscribe to the view that Schwitters was at his best during his early years, we think he was just as good during his late period.”

• Schwitters in Britain is at Tate Britain, from 30 January to 12 May

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.