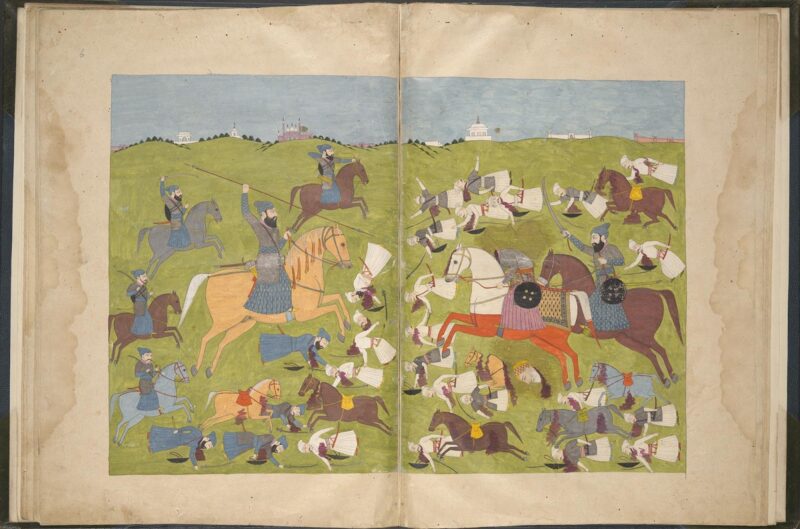

Extraordinarily complex … a detail from Luncheon in the Studio by Édouard Manet

I was enormously excited about the Royal Academy’s new Manet show, which it describes as a “landmark exhibition”. In 2003, the Prado in Madrid focused on the artist’s relationship to his forebears; and in 2011, the Musee d’Orsay in Paris located him among his contemporaries. Those were landmark exhibitions. This isn’t.

But even if this show, which opens on Saturday, cannot compare in depth or range, Manet is almost always great to look at. As well as marvellous paintings, unfinished paintings and lesser paintings, Manet: Portraying Life features curiosities and abandoned works never shown in his lifetime. Paintings the artist didn’t let out of his studio and things he walked away from are still worth seeing: a boy on a bicycle, half of which has been scraped away; or the blancmange-faced M Brun in his white trousers, walking in his garden. There’s more to brilliant artists than masterpieces. Even Manet had his off-days.

This exhibition doesn’t ask us to look at Manet in a new light, despite all the scholarship and interpretation that has been devoted to him over the decades. Instead, it attemps to examine the role of portraiture in his art. Almost all Manet is portraiture, whatever he was painting. Nowhere is this more obvious than in 1862’s Music in the Tuileries Gardens, which is given a room all its own – so that a crowd who have forgotten that the painting can usually be seen for free in the National Gallery can get a glimpse of all the tiny portraits embedded in this small outdoor scene, which measures a little over a metre across. “Oh look, there’s Charles Baudelaire! And isn’t that Théophile Gautier? Or is it Offenbach?” Recognising who is in Manet’s crowd is interesting, but it’s not everything. So one fashionable crowd looks at another, both occupying more or less democratic public spaces where the eminent and the anonymous mingle. Is this the point? Or is it just to stretch things out?

Another room is given over to a vast map of Manet’s Paris, from catalogues on tables to a sort of slideshow of photographic portraits of his sitters. This seems a bit pointless, a way of padding out an exhibition of fewer than 60 works. Also shown are some original calling cards bearing photographs, many by the photographer and caricaturist Nadar, which Manet might have referred to; his portrait of the politician Georges Clemenceau is a prime example, as it’s likely Manet had to refer to a photograph to finish it. But they are of footnote significance. Photography didn’t kill Manet’s painting – it may even have freed it from duties of likeness and formality, conventions Manet liked to play with anyway.

The exhibition opens with a room devoted to the artist and his family. Although he does appear in Music in the Tuileries Gardens, Manet painted few self-portraits. He did do a wonderful portrait of his parents, but sadly it isn’t here. In fact, I keep looking for works that aren’t here. So much is missing, and quite a bit is missable, too.

Almost any Manet, except perhaps his flower studies or still lifes, could belong here. His wife, Suzanne, plays the piano in one of several sideways-on portraits in the show, the best of which is a magisterial portrait of Émile Zola. She looks wan and stiff in this very unsuccessful pastel owned by the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio. I can’t love Manet’s smoothed, powdery pastels, which have a kind of cosmetic effect; unlike Degas’s, they have no bite. More relaxed is the 1880 impressionist portrait of Suzanne with a cat on her lap. Her illegitimate son appears in 1867’s Boy Blowing Bubbles, a painting of wonderful plainness, with one hand raised as he blows a pendulous bubble from a pipe, the other proffering a bowl of soapy water. The work is as controlled as Chardin’s paintings of the same subject. While the weightless bubble unbalances the entire composition, the whole thing is held in check by the little scrap of white rag or handkerchief peeking from the boy’s pocket.

Such little details matter in Manet: the flaring whiteness of the pith in the halved lemon in the portrait of Zacharie Astruc, with its coil of yellow peel spiralling out of the picture; the sexy peach in a bowl on a corner of Zola’s desk; the zig-zag of grey smoke from poet Stéphane Mallarmé’s cigar, his old man’s finger pointing.

Manet didn’t just paint life, he painted from life, so everyone who appears is a kind of portrait. From the outrageous Déjeuner Sur l’Herbe (the smaller of the two versions, belonging to the Courtauld Gallery, is here) to smokers and bubble-blowers, from portraits of eminent writers to one of a lion-hunter, everyone is someone – even the anonymous Street Singer, from 1862. She emerges from a doorway not singing, but stuffing her face with grapes, which are as round and full as her eyes. The model is Victorine Meurent, whose portrait Manet painted the same year. What strikes you is how clear her gaze is, how solid an object her head is. In the portrait, she is both thing and person, and declaratively made of paint. The same can be said of the two portraits of artist Berthe Morisot, the later of which shows her in mourning. It is as if the first, beautiful portrait has collapsed, under not just the weight of her misery, but of paint itself. She seems to have imploded.

What is unavoidable, even in this disappointing show, is Manet’s manipulation of the different registers of painting. Whether paying homage to the more distant past (to Rubens, Velázquez, Titian, Frans Hals and Chardin) or picking up on the realism of Gustave Courbet and the salon manners of his day, he was continually enriching his art, developing his own perverse synthesis of the past and the world around him. Although talked of as the father of impressionism, he never truly became this. His last great painting, the Courtauld’s 1882 Bar at the Folies-Bergère (not in the show), is neither realist nor impressionist. It is something beyond both, and beyond portraiture, too.

Édouard Manet was 51 when he died in 1883. Who knows what his late paintings might have looked like, had he lived to paint them. What might his subjects have been, how might he have worked, had he lived into the 20th century? You get the sense that some artists who die early have said all they had to say, while others outlive their talent. Not Manet. Realising that some of his sitters, and friends such as Claude Monet, lived on into the 1920s and 30s collapses distance – but Manet’s recentness and his modernity are different things. His paintings seem both near and far. Their details and games with space, their quotations of earlier artists and the way they embroil and distance the viewer is extraordinarily complex. Manet is great – but this show is a patchy ensemble.

• This article was amended on 22 January 2013 to correct the spelling of peeking.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.