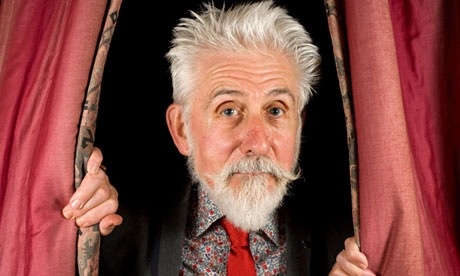

Sir Roy Strong says that some museum directors are afraid of being viewed as criticising government policy. Photograph: Rex Features

Sir Roy Strong has criticised museums and galleries for being obsessed with political correctness and blighted by a “sea” of committees and box-ticking. The former director of the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) and the National Portrait Gallery believes that a reluctance to upset anyone has led to safe and predictable themes for exhibitions.

Strong – a writer, historian, broadcaster, diarist and gardener who has been at the forefront of the British arts world for nearly half a century – said: “There’s a real fear of being controversial beyond certain [contemporary] works of art and what I call the Britart scene… I haven’t seen any museum or gallery really present anything that made you sit up and say ‘oh my God, I didn’t realise that was going on’ or ‘we’ve got to rethink that’.

“I always saw the role of director as primarily to lift people to paradise and to give them information and delight – and then, at another moment, claw them, so they were absolutely shocked and they were made to think about what was going on around them. It wasn’t all delight. It was something where you suddenly said, ‘look at this, this is going on’.” At the V&A in the 1970s, Strong staged three groundbreaking exhibitions that raised awareness of the plight of country houses, churches and gardens, warning of our crumbling heritage by showing some of the hundreds of demolished buildings. The shows had a lasting impact on public policy long after they closed.

“Nobody dares put on an exhibition that actually criticises government or public policy … The Department for Culture, Media and Sport has a very strong hold over them. They’re obsessed by political correctness.” Of museum directors, he said: “Can you think of any who’ve been controversial? We could do with a bit more derring-do.” Playing safe, he said, leads to “endless Renoir exhibitions… glamour and money”. At the mention of the V&A’s forthcoming exhibition on David Bowie, he said: “Well, we already had Grace Kelly. What she was doing there I don’t know. They’ve done a number of things like that. They’ve done that with one notion in mind – box-office and they are accessible. You have to look at it on its own merits. It’s just a balance, that you don’t do too much of it.”

It was through his three seminal V&A exhibitions that the government was prompted to give gardens listed protection, and the National Trust saw a rise in membership. Among other lasting effects, Universities also started offering courses on the issues, and a threatened wealth tax was challenged. Strong says the exhibitions changed opinions about country houses, “removing the ‘us and them’ divide”. But he believes such exhibitions would “upset the government department or politicians”.

He said religion was particularly sensitive today: “When Neil MacGregor did his exhibition on images of Christ, the culture department wasn’t very happy.It was publicly denied, but I have sources who tell me exactly the opposite. They [the venues] will be controversial about contemporary art because it doesn’t offend.”

Heritage has “very much become a dirty word”, said Strong attributing this to the teaching of history: “You’re not teaching it in schools. If you don’t produce a generation that has any time-frame, they’ve got nothing to place anything in.” An exhibition on churches and cathedrals is long overdue because of the paltry public funds they receive, he said. “They are the historic buildings above every other that is under threat. I don’t think anybody’s done an exhibition on cathedrals. That could be very interesting because in many ways they’re a huge success story and they’re something [people] passionately care about.” In an age of austerity, he suggested an exhibition on austerity, showing perhaps what people wore in the war years. “People would have an absolute shock,” he said.

In March, Bodleian Library Publishing will publish a memoir of Strong’s early career, Self-Portrait as a Young Man, in which he tells for the first time the story of the formative years of “a young man from nowhere who went somewhere”. Little has been known about his life before the 1960s, when he burst on to the scene as the revolutionary director of the National Portrait Gallery, aged 31.

Strong said that there were some “brilliant exhibitions” staged today, despite the safe choices, and the problem partly lay in the ever-increasing struggle to obtain private money and secure limited public funds with a bureaucracy of box-ticking.

Damien Whitmore, the V&A’s director of programming, said the museum community does not fear criticising the government: “We have to prove excellence. We’re all chasing audiences and sponsors… I don’t think anyone’s going to get audiences or sponsors by doing an exhibition criticising government policy… We would like to do more exhibitions about design and society.”

Dr Charles Saumarez Smith, the secretary and chief executive of the Royal Academy of Arts, and the former director of the National Gallery, said: “Roy is quite right to say that it is hard to think of agenda-setting exhibitions equivalent to his wonderful Destruction of the Country House, which certainly did succeed in capturing a public mood and changing public attitudes.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.