Into the light: a detail from the Titian portrait, which has just been rediscovered. Photograph: The National Gallery.

Tiziano Vecellio – or Titian as he is called in English – is a painter’s painter, and a lover’s painter too. His exquisite eye is charged with sensuality. Time after time he portrayed the beauties of Venice, in the long-ago days when the city was famous for its courtesans rather than its tourists (of course there were sex tourists, like the English traveller Thomas Coryate who raves about the courtesans in his 1611 book Coryate’s Crudities).

A visitor to Titian’s studio by the Grand Canal in the 1520s claimed the painter was exhausted from sleeping with his models – a claim that seems to fit the sheer enthusiasm of his paintings of women. But now his name can be linked with another, more painful aspect of sexuality in Renaissance Italy.

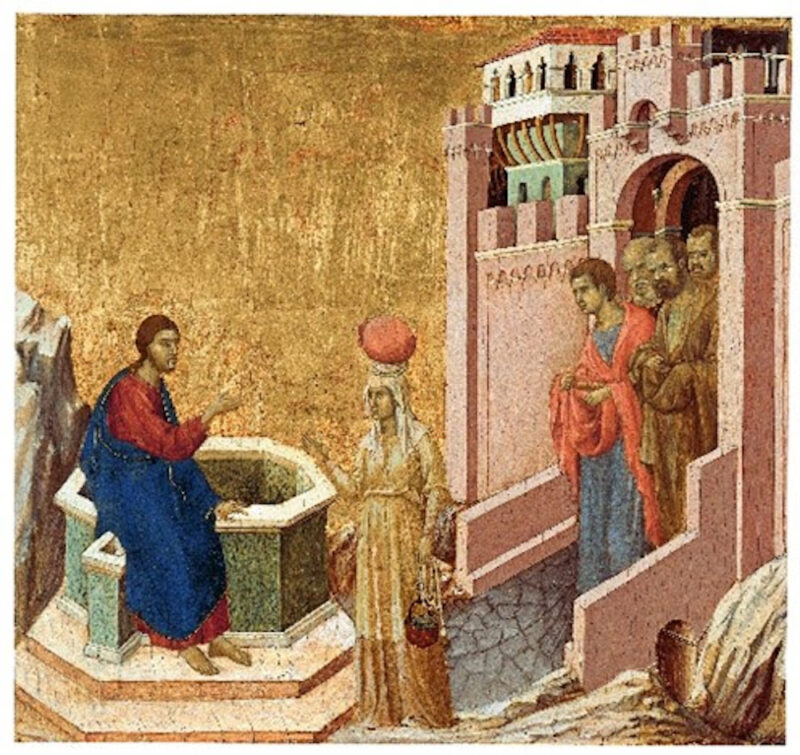

Glaring back proudly from a portrait newly attributed to Titian stands a famous doctor who gave the most terrifying sexually transmitted disease of those times the name “syphilis”.

Girolamo Fracastoro analysed the pox in an epic poem in which he coins its modern medical name. The searing infection that he was one of the first to study probably came to Europe from the Americas soon after Christopher Columbus “discovered” the New World in 1492. Italians also called it the French disease, because French soldiers carried it into Italy in 1494. It ravaged faces and bodies, and another painting of a doctor in the National Gallery was done by the artist Lorenzo Costa as a thank you for curing his dose.

Is it just possible that Titian paid for a syphilis cure with a portrait? If so, it would not be the only astonishing thing about this painting, which has just been rediscovered in the basement of the National Gallery.

As Nicholas Penny, the gallery’s director, asked himself when we met to look at it: “How can it be that buried in the bowels of the National Gallery there is a Titian?”

The National Gallery has owned this portrait of Fracastoro (his name used to be written on it) since 1924, but only this month, in an article in the Burlington Magazine, do its curators and leading scholars claim once and for all that its painting is a true Titian.

It hung for years in a remote lower room, forgotten, but now it has been brought into the light of the main collection. There, for now, the placard says “attributed to Titian”, but as Penny wonders in his frank way, “‘attributed to’ – what does that mean?”

It is a style of scholarly waffle he would like to eliminate from the National Gallery. Under the cautious language they have no doubt this portrait really is by Titian, making it the third painting by him added to the National Gallery collection since 2009.

The other two, Diana and Actaeon, and Diana and Callisto, were bought for millions of pounds. Titian’s portrait of Fracastoro has been recognised in a dusty corner of the museum at no expense at all, thanks to clever detective work and the restoration workshops hidden high in the building above Trafalgar Square.

This must mean the National Gallery now has the finest collection of Titians in the world – it already owned (among others) the elegantly frenzied Bacchus and Ariadne, the heartbreaking Easter landscape Noli me Tangere, and his portrait of a man with a mesmerising blue sleeve. But Penny, who is not given to hype, points out that the Museo del Prado in Madrid also has a few Titians. I think he is being modest.

How was this painting misrecognised for so long? When a painting is regarded as not by anyone famous and put in a museum’s dark corners, Penny suggests, a self-fulfilling process starts: curators are less likely to examine it, or clean it, or even properly frame it. But in this case fresh eyes, including those of the art historian Paul Joannides, were cast on a forgotten painting and it was taken to the lab to be restored. Discoveries there about the canvas and technique blaze the name Titian.

Fracastoro’s portrait has been damaged over the centuries, although the new cleaning by the National Gallery has revealed a very characterful face. The background is more problematic and Penny admits its clumsy architecture remains a puzzle.

But Titian’s genius flares in one fantastic detail that makes this painting – warts and all – truly captivating. “It’s not the head that is so amazing in this picture”, as Penny puts it, “but the fur.”

We are feasting our eyes on a flecked mist of white, gold, brown and black, a virtuoso, nearly abstract performance that has all the magic of Titian. With joyous freedom and a casual command of fluffy gossamer colours, the master sensualist has recreated the richness of a lynx fur hung over Fracastoro’s shoulders. “The great thing about the lynx is that it has got this brown smudge as well as black and white,” enthuses Penny about the animal whose fur Titian so convincingly copied.

He shows me how lynx fur also features in Titian’s nearby group portrait of the men of the Vendramin family – lynx was a favourite for rich Venetians.

Fracostoro worked in Verona, in the empire of the Venetian republic. As well as naming syphilis, he came up with a modern theory of contagion, saying diseases were transmitted by tiny “spores”. This was a big advance on the orthodoxy of the time that sicknesses such as plague were caused by bad air.

The lynx is an appropriate animal for such a man to sport on his shoulders, for this cat was famous for its eyesight. Italian scientific pioneers including Galileo belonged to the Academy of Lynxes, which associated the creature’s eyesight with the pursuit of empirical truth.

Now at last the scientific hero Girolamo Fracastoro, liberated from the neglect that saw his portrait sentenced to oblivion, takes his place among the gods and goddesses, patricians and prostitutes painted by one of the most beguiling magicians ever to wield a brush in what I, for one, believe is the greatest collection on earth of Titian’s paintings.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.