Sarah Lucas Bunny Gets Snookered #10

The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art has done something daring and rare. Where other art museums strive to appear dynamic through constant flux – a new wing, a new masterpiece, a new billionaire sponsor or some massive fundraising enterprise that concludes with the saving of a single painting for the nation – Edinburgh has had an unusual (and thrifty) idea.

Some months ago the Greek food magnate Dimitris Daskalopoulos offered to lend the SNGMA works from his world-class collection of modern art, which begins with Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (aka the urinal) and continues through some of the grand names of the 20th century to Joseph Beuys, Marina Abramovic and Louise Bourgeois. He would pay the insurance costs. The gallery need only take its pick.

Instead of simply clearing the decks for a tranche of this private collection, as other museums had in the past – the Whitechapel Art Gallery, the Guggenheim in Bilbao – the curators decided to match his art to their own. For every one of the 70 or so works of modern art from the SNGMA, there is a contemporary piece from the DD collection – Max Ernst and the American artist Robert Gober, say, or Otto Dix and Sarah Lucas – paired in a kind of pas de deux. The show offers a chance to see all sorts of new art generally hidden behind closed doors, but it also presents a venerable public collection in a different light.

Daskalopoulos clearly has a taste for the powerful, probing and emotive. He is, as the show’s title quotation from Beuys might imply, drawn to art that contemplates mortality, birth and death, our bodily existence. He has Rachel Whiteread’s melancholy cast of the underside of a bath, with its overtones of both headstone and sarcophagus. He has Kiki Smith’s standing women, emitting flows of scarlet cloth. He owns Beuys’s wall-sized felt cushion speared with a red javelin: a vast wound evoked by colour, contrasting softness with cold steel and sheer abruptness of scale.

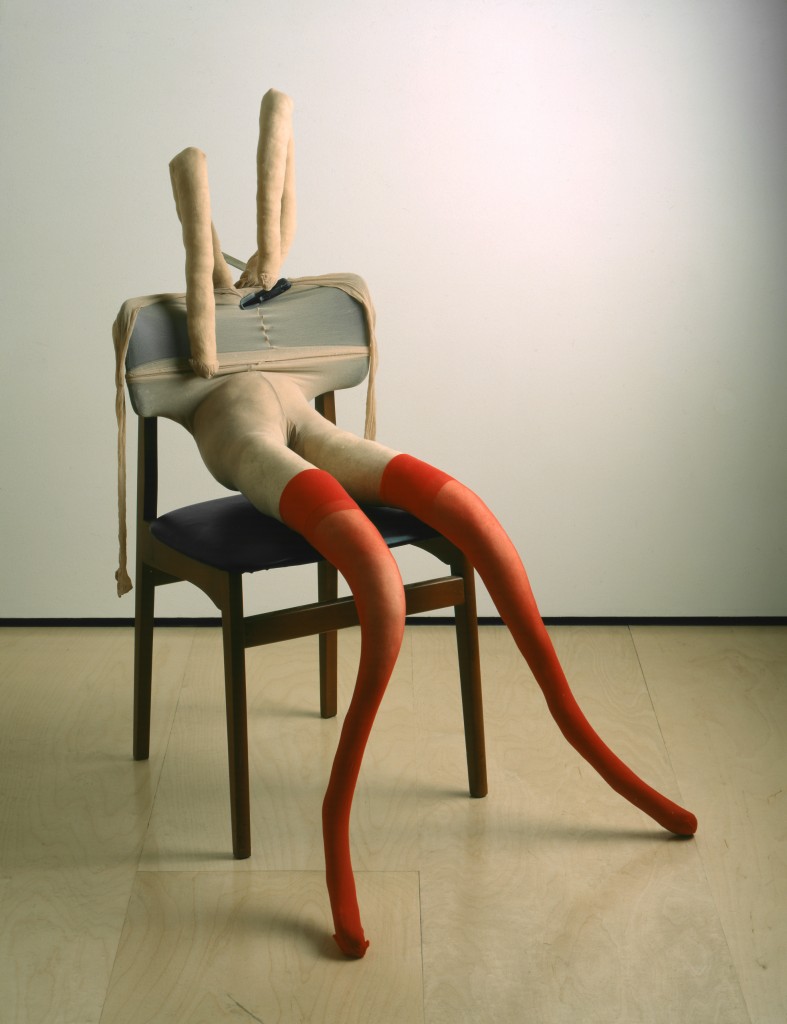

What this speaks to in Edinburgh is the SNGMA’s exceptionally strong body of dada and surrealist art, stretching back to Duchamp, Ernst and Magritte. It’s only one strain of 20th-century art but it’s extraordinarily vigorous. It is what connects Hans Bellmer’s mutant dolls from the 1920s to Mike Kelley’s abject stuffed toys in the 1990s. It is what connects Picasso’s violated nude with her exposed vulva to Lucas’s stuffed-stocking bunny girl snookered on her chair or the pictures of Max Ernst to the sculptures of Robert Gober.

Ernst’s bizarre painting Max Ernst Showing a Young Girl the Head of his Father, with its sinister nursery moon, the young figures below all shock-haired and staccato, has always seemed (to me at least) remarkably opaque. Stolid of brushwork, colours fading, it was a picture pressed so far back into art history as to be practically a period piece. But here it is paired in a single small gallery with Gober’s twisted cot – shaped like a bowtie: two barred triangles in which any child would be cruelly imprisoned. Immediately one senses the same archetypal fears, the same current of Freudian anxiety running between two works separated by more than half a century. Each work is enriched by this juxtaposition.

Daskalopoulos is very keen on Gober, indeed owns so many of his works that the SNGMA could probably have mounted an entire solo show. But although Gober is disproportionately represented, the SNGMA has one of his strongest (and least seen) sculptures: a human torso cast in wax, hyperreal but nonetheless improbable. One side is female, with a breast; the other sprouts dark hair all the way to the navel. It is a piece of received wisdom – the old yin and yang cliche – made devastatingly literal.

It gets under the skin, this human hybrid, exactly as Gober intended. And there are many other works here that have the same effect: Duchamp’s squeamish Prière de toucher, a pale pink breast swelling out of the cover of a book; Helen Chadwick‘s lightbox photograph of a human brain lovingly cupped in the artist’s own hands, as if it were hers to have and to hold.

Later one comes across Chadwick’s famous Piss Flowers, those gorgeous white flowers made by casting the space created by pee-holes in the snow, still fresh as a daisy after decades. And Mona Hatoum’s forlorn cot, lying limp as the rubber it is made from on the floor; a childhood ruined and lost. Artists and connections are not jammed together so much as threaded throughout so that one may quietly pick up a trail.

The two collections are presented on equal footing throughout, the wall captions making very little of who owns what. But anyone familiar with the SNGMA will notice many classics from its collection – paintings by Miró, Léger, Picasso and Magritte – as well as the outstanding loans from Greece.

It’s terrific to be able to view the whole of Matthew Barney’s Cremaster series in one gallery, that Ring Cycle of phantasmagorical films shot on 35mm in the blinding white salt flats of Utah, in Canada, Japan and the icescapes of Alaska, with its outlandish cast of performers including Richard Serra, Björk and Norman Mailer. The films are anything but linear, and when one sees them in one great all-together-now performance one realises how circular they are, each sweeping into the next. Deep tropes emerge – all that wax and velvet, the contrasting of scarlet and white, all the climbing, diving and struggling that goes on in these visions of heaven and hell.

And even the casual observer will have noticed by this stage in the show the strange prevalence of wax as a medium, from Beuys to Barney, in the past century of art.

Barney is unusual in having a room of his own, for the works are generally arranged to reveal affinities between different artists. Of course this cannot help producing the opposite effect on occasion. A sequence of rachitic little drawings by Tracey Emin – whose monoprints are so ubiquitous as to have become museum wallpaper – cannot compete with those of her heroine, Louise Bourgeois.

But this is an exception. The shuffling of past and present is mainly superb. Best of all is the pairing of Magritte’s painting of a mirror that reflects nothing but the words “corps humain” on its surface with Bruce Nauman’s gigantic wax ear. In fact this object is cast from the coils of a knotted rope, so that it is Knot an Ear. Nauman’s punning title circles back to the conceptual play with words and sight gags that began with Duchamp and Magritte.

From Death to Death (and so on through what is surely the longest title in exhibition history) feels spacious, spare and properly paced for slow contemplation, despite containing 150 works. Each piece, moreover, is made to work for its living: it has to have family traits, shared characteristics or at the very least resonances with the other works. And what these reveal is something more than the old truism that there is no progress in art, only change. Here is a theme that threads back and forth through the 20th century, forming a loop; and a story of art in which the past is constantly alive in the present.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.