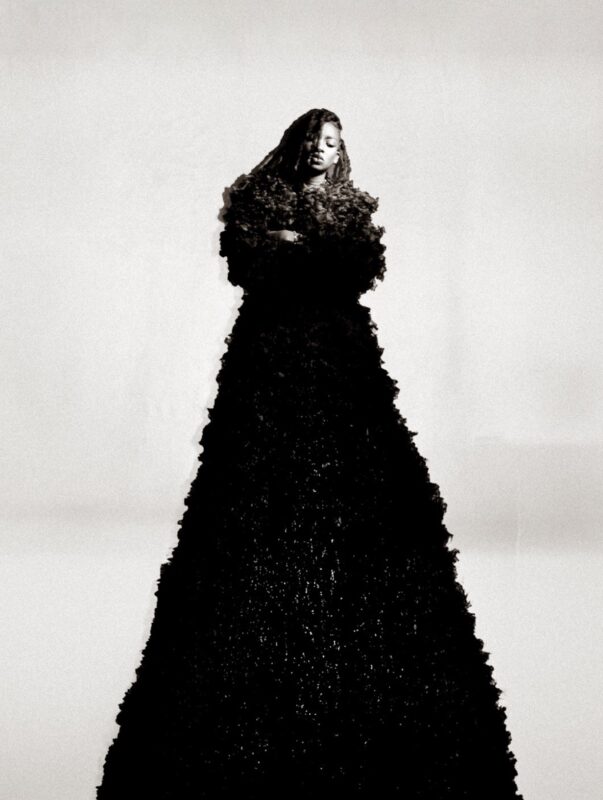

Pussy Riot. Photograph: Vanya Berezkin/Corbis/Artchronika magazine

Depending on how you define it, the most important performance by a rock band in 2012 lasted either less than two minutes or a full nine days. Pussy Riot’s guerrilla rendition of Punk Prayer: Mother of God Drive Putin Away in the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, Moscow, on 21 February was brief even by punk standards, and less striking and significant to non-Russian eyes than the band’s rooftop appearance in Red Square a month earlier. But the vindictive trial that ensued was a major international media event which revealed both the depth of the defendants’ courage and intelligence and the power of popular music to illuminate a political situation. At a recent House of Commons event organised by Kerry McCarthy MP, who attended the trial, the musician and critic John Robb suggested that the church gig was merely the soundcheck and the trial was the real show.

Contrary to Putin’s sneering remark that “they got what they asked for“, Maria Alyokhina, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Yekaterina Samutsevich didn’t set out to get prosecuted. A shrewder, less authoritarian government would have stayed its hand and let interest in the group peter out instead of breaking a butterfly on a wheel with a prosecution that reprised the tragedy of Communist show trials as farce. Once they were granted a platform that they had never sought, the three women, with admirable clarity and dignity, used it to put their accusers on trial. “The Russian authorities took a marginal act of arty protest and, through sheer cruelty, made it into an international cause,” wrote Michael Idov, the editor-in-chief of GQ Russia, adding that coverage of the trial amounted to “long infomercials against investing in, visiting and generally dealing with Russia”. Tobi Vail, whose early 90s Riot Grrrl band Bikini Kill was one of Pussy Riot’s inspirations, wasn’t being too hyperbolic when she called them “The only band that matters in 2012.”

What Pussy Riot understand so keenly is Allen Ginsberg’s observation in the 1960s that “national politics was theatre on a vast scale, with scripts, timing, sound systems. Whose theatre would attract the most customers, whose was a theatre of ideas that could be gotten across?” Viewed purely as a pop group, they are faultless: the unforgettable name, whose punchy collision of sex and violence is a feminised, radicalised take on the Sex Pistols; the uniform of bright dresses and balaclavas, which makes them both memorable and anonymous; the terse, splenetic punk racket; the unlicensed occupation of public spaces for their performances, and their subsequent dissemination on social media. In her closing statement to the court, Tolokonnikova said: “We were searching for real sincerity and simplicity, and we found these qualities in the holy foolishness of punk.”

Although their unusually tight post-trial release Putin Lights Up the Fires is as strong as many Riot Grrrl records, Pussy Riot are, like only a handful of western bands – Crass, Public Enemy, the Last Poets – political provocateurs first and musicians second. They make words, image and noise tell the same story, so that you can see them in action for one minute and still get the message.

Some seasoned Russia-watchers have grumbled about young women in colourful balaclavas receiving immeasurably more international attention than other persecuted dissidents. They might as well complain that rain is wet. Pussy Riot are clever and committed enough to express themselves in more sober ways if they wanted, but they chose to exploit the media to the hilt because they know how it works – in the words of 60s Yippie activist Abbie Hoffman, they “fight through the jungles of TV”. Their fame has not eclipsed other injustices in Russia but highlighted them, in the tradition of opposition movements strategically promoting charismatic individuals, from Nelson Mandela to Ai Wei Wei, as synecdoches for an entire cause. For newly curious observers outside Russia, Pussy Riot have lifted the curtain on the regime’s intolerance.

There is nothing accidental about this and nothing trivial about the women themselves. We are used to musicians making inspiring protest songs then fumbling the follow-up as they try to paper over the gaps in their knowledge with stirring simplifications. Not Pussy Riot. They sprang, in October 2011, from the anarchist art collective Voina (meaning “war”), with an arsenal of political theory. The scope of their concerns is broad, from education and healthcare to feminism, LGBT rights and Russia’s culture of conformity. Two of them were arrested for taking part in Moscow’s banned Gay Pride rally last year. Their concerts, by laying claim to public spaces, are Situationist-inspired acts of dissent even before a note has been played. It’s perhaps misleading to call them a band. The five who performed in the cathedral (two fled the country to avoid arrest) are only part of a shifting collective that numbers up to 20. Tolokonnikova sees their work as “modern art“.

Samutsevich told Rolling Stone: “Art has become only more complicated. Now it’s done internationally, and it has great political potential. An artist is a person who is constantly analysing critical thoughts, always working out an independent opinion regarding everything. That is why art gives a breath of fresh air and a different way to protest.”

So when the prosecution depicted them as Satanic hooligans and their defence team, complained Samutsevich, “made us look like teenage girls that went against Putin without even understanding why they are … doing it,” the trio proved themselves to be calm, courageous, impeccably well-informed women, whose eloquent statements to the court quoted Dostoevsky, Solzhenitsyn and Joseph Brodsky. “Compared to the judicial machine, we are nobodies, and we have lost,” said Samutsevich. “On the other hand, we have won … The system cannot conceal the repressive nature of this trial. Once again, the world sees Russia differently than the way Putin tries to present it at his daily international meetings.” Even some members of Putin’s United Russia party agreed, with one publicly complaining the indictment “makes the country the laughing stock of the entire world.”

The closest US analogue to the Pussy Riot case is the trial of the so-called “Chicago Seven” for conspiracy to riot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. It was likewise feverish, absurd and symbolic of a clash between the state and a new generation of protesters. As it ended, Abbie Hoffman gave Judge Julius Hoffman (no relation) a copy of his book, Do It! Scenarios of the Revolution, with the inscription: “Julius, you radicalized more people that we ever could. You’re the country’s top Yippie.” A similarly barbed compliment could be bestowed on judge Marina Syrova.

It is only when you pan back from the courtroom and consider the overseas Free Pussy Riot campaign that the picture becomes more complicated. It quickly became the celebrity cause du jour. Yoko Ono gave Pussy Riot the Lennon Ono Grant for Peace award. Paul McCartney wrote them an open letter. Björk and Patti Smith dedicated songs to them. Peaches released a song called Free Pussy Riot with a video crammed with celebrity supporters.

The band were coolly grateful for all support, and their lawyers acknowledged that the international outcry helped to secure relatively lenient jail terms and free Samutsevich on appeal, but the circus of western celebrity sits uneasily with Pussy Riot’s stern rejection of fame and capitalism. “We’re flattered, of course, that Madonna and Björk have offered to perform with us,” a member using the pseudonym Orange told Radio Free Europe. “But the only performances we’ll participate in are illegal ones. We refuse to perform as part of the capitalist system, at concerts where they sell tickets.”

Madonna, specifically, deserves credit for championing the band at her Moscow concert during the trial, but not for selling Pussy Riot T-shirts in her online store. This is a band for whom “selling out”, an increasingly archaic concept in the west, is unimaginable. They are currently at odds with their former lawyers over the fate of the Pussy Riot brand – wanting to keep it out of the hands of unscrupulous merchandisers. They have also criticised copycat protests outside Russia and chastised young women hoping to follow their example without doing the intellectual spadework. “They don’t know about feminism or art,” said Samutsevich. “They say we are against Putin and that’s it. I can’t prohibit it, but I don’t approve of it … Any person can put on a balaclava, it’s all very good, but it’s important that the ideas are not warped.”

Certainly the international frenzy around Pussy Riot involves an uncomfortably voyeuristic fascination with a situation in which punk can land you a prison sentence rather than a Converse advert – a nostalgia for the outlaw frisson that music once possessed in the west. And slogans such as “We Are All Pussy Riot” downplay how abrasively radical their ideas and methods would be even in London or New York. But any threat of Pussy Riot becoming cuddly icons – “Manic Pixie Dream Dissidents” in writer Sarah Kendzior’s phrase – is dispelled whenever the women themselves speak, with a distinctly Russian severity and blade-like clarity of purpose. When Der Spiegel interviewed Tolokonnikova in the penal colony, she regretted nothing: “If you’re afraid of wolves, you shouldn’t go into the forest. I’m not afraid of wolves.” So far they have used the machinery of pop far more than it has used them.

Pussy Riot have vowed to continue although their future is uncertain. The remaining members are in hiding. The Russian government has labelled their videos “extremist” and thus illegal. Samutsevich and Tolokonnikova’s husband, Pyotr Verzilov, have separately been accused of being Kremlin agents. The Russian public, including many fellow musicians and opposition politicians, has failed to rally to their defence. Pro-regime newspapers seize any excuse to run smear stories about the women. “Pussy Riot Finished,” crowed Rossiyskaya Gazeta, hopefully prematurely.

Pussy Riot, both in and out of jail, are doing what they can. For their sympathisers the challenge is to neither forget nor romanticise them. They are not our cute punk pin-ups but unflinching hardline activists whose work demands a response on two fronts. Their supporters need to keep agitating on behalf of the jailed women and their less well-known fellow dissidents. And musicians and artists who live under less wolfish regimes should use Pussy Riot’s inspirational example as a spur to action.

As Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna wrote during the trial, “This could be the start of a whole new thing, a whole new motivating source for a globally connected unapologetic punk feminist art and music scene. A catalyst, no matter what it gets called. Anything is possible. If anything, this band has reminded us of that.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.