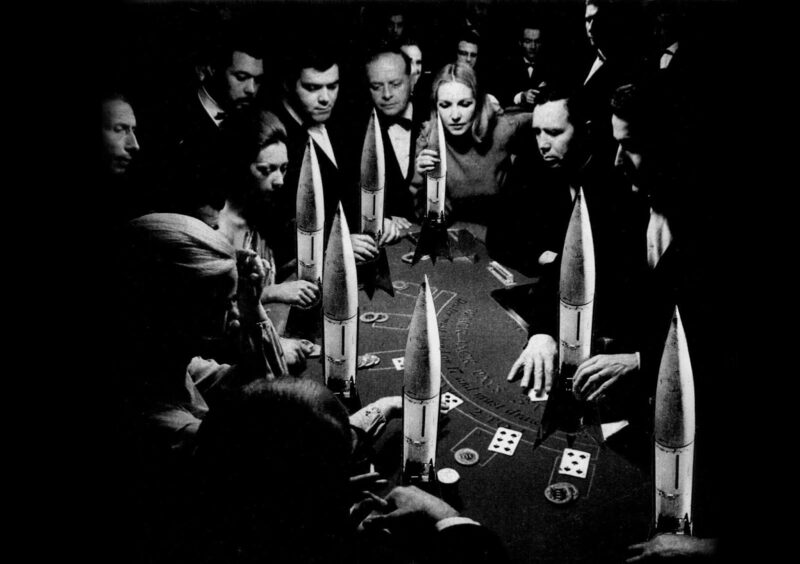

Kept at a distance … a detail from Inhabited Painting, 1975, by Helena Almeida.

Jackson Pollock and David Hockney are a strange coupling. They occupy the first room of Tate Modern’s new exhibition A Bigger Splash: Painting After Performance. The 1948 Pollock, called Summertime: Number 9A, sits on a raised section of floor, under glass, with a clip of Pollock playing above it, from Hans Namuth and Paul Falkenberg’s grainy 1951 film. On the other side of the room, Hockney’s 1967 A Bigger Splash hangs alone. Nearby, footage from Jack Hazan’s 1973-4 colour film, A Bigger Splash, of the artist’s glamorous California life and loves plays on a screen.

I try to listen to Pollock talking, but my concentration is shattered by a phone ringing in the Hockney clip. “Hi Jacko, it’s David,” I imagine the conversation going, as they swap paint recipes. But it doesn’t happen. In the Pollock film, the artist spends a long time struggling into his spattered old workboots before leaning over a skinny length of canvas, loading a brush, then dribbling and flicking paint over it, first from one side, then the other. Meanwhile, Hockney looks owlish and neat in round glasses as he tints the coiffure of a male portrait a shade darker with a small brush. While Pollock works up a rhythm on one screen, a naked young man plunges into a pool on the other.

The room seems to be all about oppositions: vertical and horizontal, spontaneity and calculation, figuration and abstraction, gay and straight. Hockney took two weeks to paint the splash caused by a dive, with its little passages of tiny dots, curly white lines, and carefully executed passages of overlayed hatching and tonal gradations. The Pollock just seems to happen. But so what? In the end, a Pollock is as calculated as a Hockney, and the pairing feels like an irritating academic conceit.

All painting is a kind of performance. I guess curating is, too. Bodies present and absent are at the heart of this awkward and largely disappointing exhibition, which sets out to examine the relationship between painting and performance art since the 1950s. Niki de Saint Phalle used a gun to shoot holes in paint-filled balloons stuck to lumpy canvases. Kazuo Shiraga suspended himself in a kind of Japanese rope bondage over a canvas and painted with his feet. This is a famous mess. The Viennese actionists Otto Muehl and Günter Brus and their friends mud-wrestled in paint, which was even messier, but not as shocking as Stuart Brisley’s performances – which, in black and white photographs, look distinctly coprophagic, a kind of dirty protest. (There’s too much photography here.)

Video footage of Yves Klein using naked women as living brushes or stencils is accompanied by a blue monochrome that has nothing to do with his Anthropometries, as the canvases that came out of these staged performances were called. This is a pity. Similarly, the film of Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica and his friends dancing while wearing his painted capes needs to be screened larger for the euphoric, languid energy to come across. But I did enjoy the repeated up-crotch shots of Oiticica’s unartistic underpants.

Oiticica went on to commission a series of photographs of drag queen Mario Montez on the streets of New York. There’s quite a bit of cross-dressing, body paint and slap throughout the show: Warhol as Marilyn, Zsuzsanna Ujj painting a skeleton on her own skin. Paint can be like mud or faeces, and it can be delicate as makeup; it can adorn or besmirch, beautify or degrade. I wish there were a bit more of it here, and a few more real performances. So many of the artists here cry out to be dealt with in their own full-on, ecstatic, dirty, smelly, sexy, theatrical, orgiastic, atavistic, abject and even frightening ways. But they’re not. It all feels like a very goody-two-shoes Tate show. Everything is kept at a distance. What the show rarely does is give you the feeling that paintings, let alone performances, are made by bodies.

We are tethered by earphones to video screens, kept on the threshold of stage sets in which there are no performers. There is very little sense of our own bodily engagement, of one’s own performance as spectator. Where’s the jolt of confrontation, our desires or repulsion as viewers?

Karen Kilimnik is known as a painter, but her stage set for Swan Lake adds little to our understanding of any relationship between painting and the stage – one still, the other a place for action. Fake fog drifts, along with Tchaikovsky, through the gloom. Performance pioneer Joan Jonas is represented by a stage set, for her theatre piece The Juniper Tree. There are painted elements, along with a real kimono, wooden balls, and a figure made of sticks with a mask for a head – but so what?

Shots of Valie Export in androgynous man-drag, Cindy Sherman in various early photoshoot guises, and the gender play of Andrew Logan’s Alternative Miss World, of Leigh Bowery, Urs Luthi and others all tell us something about how gender – as well as age or race – can be performed through dress, cosmetics and body language. But surely this is another show? This is something other than painting. A Bigger Splash nods to queer aesthetics and politics, to the transgression of social and artistic normative values, but it doesn’t go nearly far enough. It short-changes its subject. Much of it is little more than a checklist – a bit of photo-documentation here, a video there, a lone unstretched painting here.

A few photographs of Portuguese artist Helena Almeida walking between canvas stretchers, or overpainting her reflection in a mirror, give very little idea of her powerful performance works. The piece with mirrors and blue electrical tape by Polish artist Edward Krasinski is interesting enough, but to really understand how bizarre his work is, you need to visit the late artist’s preserved Warsaw apartment, which I was lucky enough to do last year. Krasinski had a perverse and absurd approach to living and performing the role of the artist that doesn’t come across here.

At least Marc Camille Chaimowicz‘s room-sized installation, loosely themed around Jean Cocteau, has the feeling of a whole world – with its wallpapers and furniture; paintings by Vuillard, Marie Laurencin and Duncan Grant; a Warhol Electric Chair screenprint; and numerous furnishings either built or arranged by Chaimowicz himself. Sadly, you can only stand on the brink, looking in. It does, however, give a sense that a whole life is to be performed.

The show’s final space, by Lucy McKenzie, is rather beautiful. Are these paintings or a stage set? The whole thing is an imaginary room, with walls, fake marbling, trompe l’oeil radiators, a phone on the wall, the scuffs and stains and desuetude of a formerly elegant house, subdivided for multiple occupation. It’s brilliantly done. This is a set for an imaginary version of Muriel Spark’s 1963 novella The Girls of Slender Means. The whole thing has a feeling of sadness, of life as anticipation and anticlimax. What a performance it all is.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.