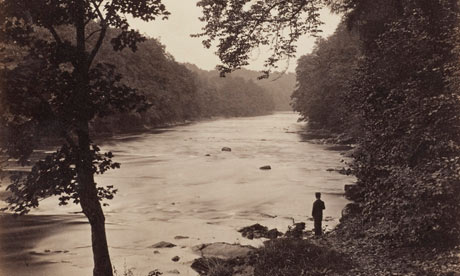

Paradise by Roger Fenton. Photograph: Courtesy of the National Gallery, London

What was it like to see the earliest photographic portraits for the first time, almost two centuries ago? Elizabeth Barrett Browning was astounded. “They are like engravings – only exquisite and delicate beyond the work of the graver,” she wrote, marvelling that these silvery images represented “the very shadow of the person lying there fixed forever!”

A photograph of a loved one must be better than a painting, she argued, precisely because it was such a direct personal manifestation. There was no mediation, only the action of light. In fact, the little pictures Barrett Browning saw involved elaborate poses, complex lighting, feats of motionless sitting for long exposure times, the powdering of hair to make it look brighter, the blending of facial tones using fine-ground pigment to give added life and even the gilding of the final image to make it glow. The new medium of photography learned much from the old art of painting.

The relationship between the two is the subject of the National Gallery’s first, somewhat belated, major photography exhibition. But in this case, better late than never. For Seduced By Art is an enthralling show, beautifully selected to express the numerous ways in which painting has inspired or affected the evolution of photography. It has work by contemporary art photographers such as Nan Goldin and Thomas Struth, but most of the pictures are 19th century, and not the least of its pleasures is the intermingling of paintings by Goya and Degas, say, with photographs by Fox Talbot and Nadar.

Indeed the show opens with Delacroix’s singularly strange picture, The Death of Sardanapalus, in which the Assyrian king is supposed to be torching his palace rather than surrender to the enemy, but is depicted as a tiny stalled figure detached from the deadly chaos around him. Jeff Wall’s photographic reprise in lifesize cibachrome print goes to the heart of this bewildering atmosphere.

Wall’s photograph is stuffed with opulent garments, gewgaws and jewels – and then unstuffed. The scene is literally falling apart, from the slew of props to the set. This is the aftermath of some human disaster, one feels, even while distracted by the tilting composition, the dramatic interplay of light and hue, and the gorgeous colours.

In short, you’re in the same position as Sardanapalus, unable to concentrate on what matters. You experience Wall’s picture as if it were a painting, instead of a photographic record of terminal wreckage. It is a beguiling and mysterious work, no less so for being entirely empty of people; and in far exceeding imitation, it becomes a good starting point for this show.

When the medium was first invented, photographs were expected to resemble the painted fictions that preceded them. But each partook of the reality depicted. Julia Margaret Cameron‘s images of children may look remarkably like the paintings of her mentor GF Watts hanging alongside, rapt and ethereal, but Cameron is able to infuse – and enhance – her version of their shared vision with the real-life innocence of her sitters.

Adolphe Braun’s wonderful flower studies may look remarkably like the still life paintings of Henri Fantin-Latour, but Braun came first. His superb photograph of hollyhocks from the 1850s somehow manages to evoke subtle shades of pink, mauve and blue in its monochrome tones. Black and white photography was colour-blind in those days, registering blue as white, yellow as grey and red as black shadow. But Braun used gold-toned salted paper, varnished to enhance the depth of shadow, and worked with the finest adjustments of lighting to achieve his effects. His flowers appear ancient and yet fully living.

The Israeli photographer Ori Gersht, by comparison, takes Henri Fantin-Latour’s The Rosy Wealth of June and blows it apart. A vase of June roses is seen gradually exploding in freeze-frame, the petals blossoming into starry pinpricks in the characteristic darkness of Fantin-Latour’s backdrops. These split-second shots show off the extraordinary advances in modern technology but they also invoke the slowness of painting by contrast, the way a painting communicates gradually and partially, unfolding itself over time.

Our access to painting now comes largely through photography. We see old masters given artificial radiance on our computer screens. We buy postcards, imagine that paintings are concise as reproductions. Auctions are conducted online, with buyers bidding sight unseen. We see images, we don’t look at paintings.

Dwelling upon this melancholy truth, the Finnish photographer Jorma Puranen photographed Goya’s The Duke of Wellington to expose its inner tensions as a portrait. Puranen’s light catches the brush’s passage, the sheen of varnish, the topography of pigment and canvas so that paintings emerge as physical objects.

In this instance, the picture has a split personality. The body in its scarlet costume turns out to be thick with impasto medals, confidently worked in comparison to the pale and uncertain head. One perceives the distance between artist and subject; Wellington is a wraith from some other world to this leery Spaniard.

Anyone who has ever wondered how paintings might translate into reality might look at Tom Hunter’s replay of the concubine from Sardanapalus as a modern woman face down on a bed (and thus no longer nude so much as naked). Anyone who wants to know why contemporary reconstructions are inevitably kitsch can examine the work of Maisie Broadhead and Martin Parr. And the rise of an art photography that refers back to old paintings in scale and ambition is explored through the monumental images of Jem Southam and Struth with their devoutly objective overtones, an antidote to the tricksiness of postmodernism.

The show is full of revelations (for me, at least), including the startling semi-abstract forests of Gustave Le Gray from the 1850s and the bizarre figments of Oscar Gustav Rejlander, a Swedish photographer who settled in Wolverhampton around the same time.

Rejlander made his name by blending vignettes from the old masters – Vermeer’s astronomer, Raphael’s Madonnas – into wildly allegorical panoramas, brushing velvet across the plates to smooth the transitions; the analogy with painting is again irresistible.

But the English photographer Roger Fenton is the star of this show. Look at his beautiful image of a boy on a riverbank from 1859. It is composed contre-jour (against the light) so that the leaves in the trees have beautiful fluttering halations; it has aerial perspective, so that the receding landscape is hazy to the eye compared to the foreground; and it has tragic overtones. Fenton’s son had died and this was one of the last photographs he ever took. The boy stands on the shore watching the silver river wind away into the unknown.

Fenton makes a narrative in the same way a painter might, and he used the viewing screen of a large plate camera to modify the composition in advance, like a canvas. But his medium is not paint so much as reality, and that is what makes his great images so poignant.

On the Crimean battlefield there are barely two dozen soldiers of the 1st Staffordshire Regiment still standing, arranged like a row of cartridges against the smoking sky. They are already shadows of themselves, almost, except that some slight movement keeps them alive before the witness of Fenton’s camera.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.