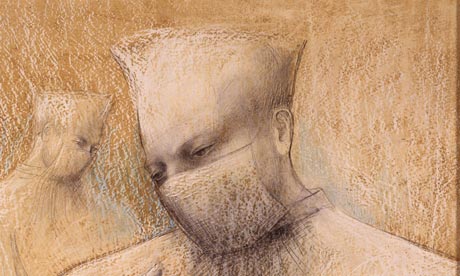

A portrait of virtuous toil … Detail from Concentration of Hands II (1948) by Barbara Hepworth. Photograph: Bowness, Hepworth Estate. Image courtesy of Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert

In 1947 and 1948, as Labour minister Aneurin Bevan wrestled with creating a National Health Service, an artist undertook her own personal investigation into the state of medical provision in Britain.

Barbara Hepworth was by then famous for her organic abstract sculptures, carved in wood and stone. She usually worked in the pure atmosphere of her studio in the Cornish town of St Ives, where she and her family had moved at the start of the second world war. But marble was short in austerity Britain. So Hepworth moved from chipping away in solitary splendour and set out to draw people up close, taking her sketchpad to an operating theatre in Exeter after befriending a surgeon at Princess Elizabeth orthopaedic hospital. The results feature in The Hospital Drawings, a new exhibition at the Hepworth Wakefield in Yorkshire.

I have had difficulty keeping up with Hepworth’s rising fame. After decades as a respectable but semi-forgotten figure from a lost age of British abstract art, she is suddenly a name to be reckoned with. Why? I don’t have any objections – her sculptures echo the geological beauty of rock crystals or ammonites – but I don’t get the compulsion to rediscover her, either.

Or I didn’t, until I saw these drawings. Like the 1945 Labour government, these arresting works of socialist art glow with a common purpose, as her subjects concentrate on a shared task. What’s striking is the prevalence of all those masks, covering half of the face and obscuring all the usual signifiers of emotion and intent. We find ourselves directed instead to the eyes of surgeon Norman Capener and his team. Although Hepworth’s drawings are steeped in art history – these figures owe a lot to the Renaissance painter Piero della Francesca – they have the gripping quality of TV medical dramas. Look into the eyes of the surgeon and his devoted assistants and you’ll see the heroic rescue of another patient.

But there’s a passion here that goes beyond simple facts, beyond surgical soap opera. Hepworth’s friendship with Capener, which started when he operated on her daughter, was intense: she helped him become an amateur artist; he wrote about her; they may have been lovers. It is not hard to believe she is was love with the man she depicts as a godlike figure, delicately putting on his gloves, eyes full of compassion.

The atmosphere goes beyond hospital romance, though. Hepworth’s art becomes a medical marvel of its own. She turns what she sees into a myth. The hats could come from ancient Egyptian wall paintings. And where is the gore? Only once do we even glimpse a patient. This is about eyes and hands moving in tandem, a surgical team working together in perfect harmony – at a task that is indisputably virtuous.

In 2012, the NHS is threatened, its future uncertain. In Wakefield, like everywhere else, there are signs that austerity has returned. Where are the values that protected British people back then, creating the NHS just as Hepworth was glorifying such common labour? Near the station, a once-grand trade union hall stands empty.

Hepworth was a Labour voter – of course she was. In these drawings, she reveals her egalitarian values. Work is goodness: she sees her own work as a sculptor reflected in the steady eye and hand of the surgeon. In one drawing, he even seems to wield a hammer and chisel. But this is not mere artistic self-consciousness. The work being done in these pictures saves lives; Hepworth believes her art, too, can heal souls.

In the gallery’s main collection, I was struck by a white marble megalith carved by Hepworth. In her sculpture, I realised, she almost never leaves a trace of her chisel – unlike Michelangelo, who deliberately left evidence of his efforts. It is strange that an artist who put so much into her creations went to such lengths to hide that effort, to make her objects seem geological rather than human. It surely has something to do with an idea of virtue: honest toil demands no applause.

Similarly, these drawings do have a sculptural purity, a weightiness that suggests they were somehow hewn from marble – but their creator is not nearly so invisible. For once, we glimpse the idealist behind the mask.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.