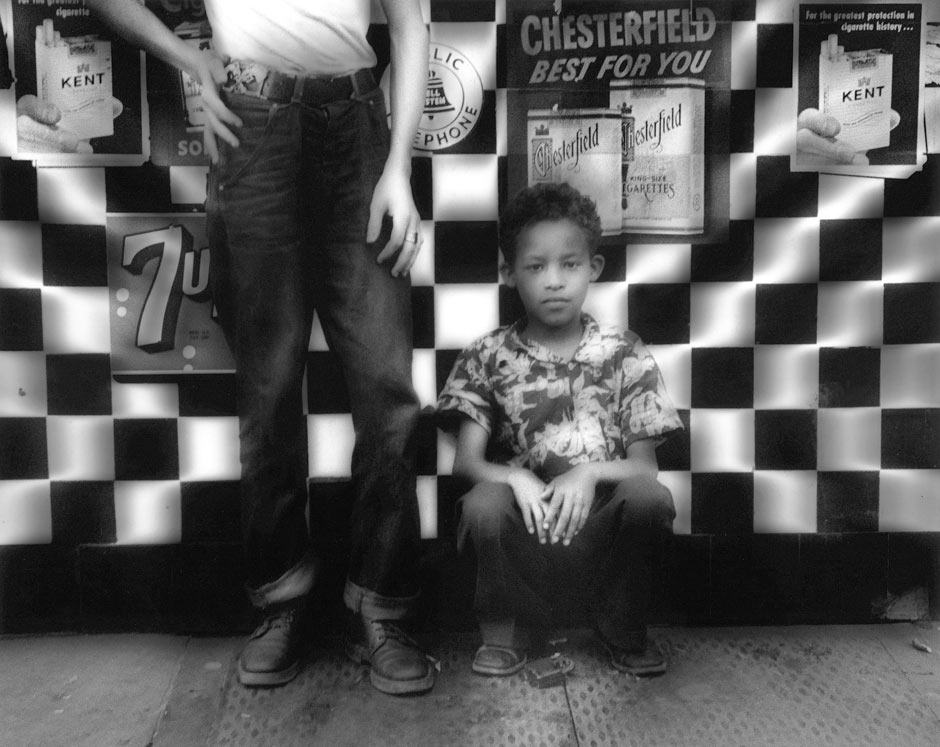

William Klein’s Candy Store, New York, 1955: ‘a sense of creative restlessness’. Photograph: William Klein

As you enter the first room of this ambitious exhibition devoted to two pioneers of postwar photography, it is one of William Klein’s early films that serves as a deceptively gentle introduction. Made in 1958, Broadway by Light is a homage to colour, light and the now nostalgia-tinged magic of the giant flickering advertisements that throw their dazzle and shimmer on to the rainy sidewalks of midtown Manhattan. It is a playful film, a kind of extended visual jazz riff on the nocturnal cityscape that so entranced the restless young Klein. The film gives little indication of the photographs that follow, which give full expression to Klein’s free-form exploration of movement, energy and graininess. That energy is punctuated here and there by the occasional moment of stillness, mostly in his portraits.

Klein’s training as a painter under Fernand Léger is evident throughout, both compositionally and in his famous application of bold primary colours to his contact sheets, which here have been blown up to fill entire walls. There is also a room devoted to his paintings, which merge typography and a bold constructivist style. What unites his work is the sense of creative restlessness, which led him from painting to photography and on to film. There is a sense, too, of someone at home in whatever world he finds himself subverting, whether portraiture, fashion or street photography.

The momentum and scattergun vision of Klein’s work are, on one level, a preparation for Daido Moriyama’s images, which take up the second series of rooms in this maze of an exhibition. But, though the two artists have been brought together by Simon Baker, the Tate’s curator of photography, this is essentially two separate exhibitions. The viewer walks though the Klein show into the Moriyama show, and is forced to find connections that might have been more easily made, and dramatically illustrated, if the work of both had been shown side by side.

Moriyama’s gaze was influenced by Klein’s book, Life is Good & Good for You in New York, first published in 1956, which announced the American photographer’s use of grain, blur and movement to capture the fast-forward energy of the city. Just how influential Klein was on Moriyama can be measured by an essay the latter wrote in 1980 after visiting Klein in Paris. It is titled “Finally I Meet William Klein, Whom I Can’t Get Out of My Head”.

By then, Moriyama had already extended and subverted Klein’s fast-moving approach, often making books where the idea of context – and even subject – was jettisoned in favour of something more impressionistic. Moriyama’s cityscapes are realms of the imagination, full of dark suggestion and ominous shadows. On the walls of Tate Modern his work does not work the way it does in his myriad photobooks, which shape – you could even say curtail – his frenetic style into a series of impressionistic diaries. Without the book format the images often seem unmoored. Moriyama’s best known book is Farewell Photography, the title of which gives some idea of his radical approach. In it, as Minoru Shimizu notes in his catalogue essay for this show, “grainy, blurry, out-of-focus is a method of annihilation: no meaning, no expression, no sense of the photographer”.

And yet, for all that, as this exhibition shows, Moriyama has a visual signature that is perhaps even more immediately recognisable than Klein’s. His obsessive monochrome vision does not let much light in and there is nothing approaching Klein’s bright, sometimes garish use of colour or the exuberance of his fashion shoots, where the street, with all its energy and movement, seems to galvanise the models.

Moriyama is an outsider by temperament and artistic inclination. His vision is dark, edgy, experimental. He prowls the city, his abiding subject, like the wolfish stray dog with the haunted eyes in his most famous photograph. It could almost be a symbolic self-portrait, though it is perhaps a little too sinister, too predatory. His work is more subtle than that. It draws you back, not just through its depiction of the atmosphere and sensations of a city, but in its shifts of style and methodology as he explores the limits of photographic representation. The room devoted to his huge composite grids, which often rework the themes of earlier single images, is a revelation just for his dip into formalism and muted colour.

Ultimately, though, Moriyama’s vision is dark in every sense. No one else takes photographs as ominous as the flatly titled Record No 1 1972, a partially clogged city drain at night-time, all light and shadow, shiny and coagulated. For every glimpse of a human figure, there is a study of discarded bottles, fallen leaves, electrical wires on grey concrete, cracked human lips in close-up. Like the late Garry Winogrand, Moriyama often seems to be intent on photographing everything, however mundane or throwaway. His photographs may baffle some as much as they enthral, but they make sense as a dark extended coda to Klein’s more energetic vision. More than that, they are a glimpse of a singular imagination at work and one as obsessive as any in recent times.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.